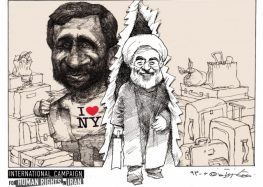

President Hassan Rouhani

Citizenship rights

Citizenship rights

The Political Crimes Bill

Abuses by herasat offices

Notices of constitutional violations

Free speech

Women’s rights

Discrimination in government employment practices

The encouragement of government transparency

In this report, the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran highlights human rights violations occurring under the purview of nine Iranian government ministries that report directly to the Iranian president. The new administration, led by President Hassan Rouhani, has the authority to stop and prevent these violations, and the report provides specific, actionable recommendations aimed at stemming the violations.

In addition to the activities of the ministries under executive control, the president of Iran also has specific powers and areas under his direct control that afford him significant ability to affect the state of human rights in Iran. For example, the president can introduce legislation to Parliament, issue executive orders regarding government practices, and, as the chief enforcer of the Iranian constitution, hold state institutions accountable to the law by monitoring and noting violations of the Iranian constitution by state institutions.

In this section, actions that President Hassan Rouhani can take directly and immediately to fulfill his campaign pledges to uphold the rights of the Iranian people are highlighted.

The Fourth Development Plan, which was adopted as the state’s comprehensive guiding plan by the government and Parliament of the Islamic Republic of Iran in 2002, includes a requirement that the executive branch introduce and the Parliament pass legislation detailing the specific rights of Iranian citizens. The purpose of this legislation is to gather and detail in domestic law the various rights enumerated in the country’s constitution and to incorporate into such legislation the Iranian government’s obligations under international human rights conventions to which it is a party.

However, this aspect of the state’s Development Plan has never been implemented. In 2005, then-President Khatami introduced to the Parliament such mandated legislation, which included a “Citizen’s Rights Bill,” legislation on “Privacy Rights,” and a “Freedom of Press and Access to Government Information Law,” but Parliament failed to debate and vote on any of these legislations.

At present, Iranian rights are codified only in the constitution, and only in the most general terms, with no specific delineation or definition of these rights.

President Rouhani can and should re-introduce and actively pursue the passage of these three mandated legislations in the Iranian Parliament so that the rights of Iranians are specifically codified and legally binding, and are in accordance with international human rights law. He should use all the powers of his presidency to ensure that these laws are debated, voted on, and passed in the Parliament, assigning this issue the prioritization it must have, given the widespread and systematic abuse of rights in Iran that are ostensibly protected by the Iranian constitution.

Given the Iranian president’s ability to introduce legislation and his capacity to use the powers of his office to lead and persuade on legislative issues, Rouhani can and should actively push for the passage in the Iranian Parliament of a Political Crimes Bill. This bill would clearly delineate those political activities that are legal in Iran, and those that are not. Importantly, these delineations would be in full accordance with international human rights laws, including those that guarantee the freedoms of speech and association and freedom of the press. This would not only protect internationally accepted norms of political activity inside Iran, it would also prevent the Iranian authorities from arresting and imprisoning Iranian citizens arbitrarily on vague “national security” charges.

A Political Crimes Bill was originally introduced to Parliament under the reformist Khatami administration, but it has languished unapproved since then. Decades after the Islamic Revolution, there is still no definition of a “political crime” in the Islamic Republic of Iran, and hundreds of people are imprisoned each year in Iran for their peaceful social and political activism.

In addition, Article 168 of the Iranian constitution states that “political and press offenses will be tried openly and in the presence of a jury, in courts of justice.” However, with political crimes left undefined, individuals arrested and imprisoned for their journalistic activities or in relation to their political activities under vague national security charges are rarely tried in open courts or in the presence of a jury.

The new President should re-introduce a Political Crimes Bill, ensure that the definition of a “political crime” is based on the constitution and complies with Iran’s international obligations in this area, and use his full capabilities to have this law approved in the Iranian Parliament.

Abuses by herasat offices (local state intelligence bureaus)

Herasat offices are found in state institutions and universities throughout Iran, and are comprised of representatives of the Ministry of Intelligence who monitor such institutions in order to ensure continued fealty to the Islamic Republic and “prevent penetration” of any state institution by those deemed disloyal to the regime. They are found in every government office, in state-owned enterprises throughout the Iranian economy, in the state-run media, and in all of the universities, where they conduct surveillance, monitor private communications, act as informants, and influence hiring and firing practices. Members of the herasat harass, intimidate, and engage in widespread human rights abuses, and, in particular, violate Article 23 of the Iranian constitution, which states that “the investigation of an individual’s beliefs is forbidden, and no one may be molested or taken to task simply for holding a certain belief.”

For example, the herasat offices in Iranian universities play a major role in the suspension and expulsion of students who engage in political or religious activities with which the herasat disapproves, or who dress or engage in conduct with which they disapprove. Herasat offices have deprived hundreds of Iranian students of their right to education because of those individuals’ legal political activities and the expression of their opinions.

President Rouhani must review and evaluate the policies and actions of the herasat, ensure that its members do not continue to engage in the systematic violations of human rights, and, if they do violate the laws, that they not enjoy immunity from legal and criminal accountability. Additionally, the president must create effective legal and oversight mechanisms to ensure that the employment and/or dismissal of students, professors, or employees is not based on an individual’s beliefs.

In addition, according to Article 127 of the Iranian constitution, the president may, in special circumstances, appoint one or more special representatives with specific powers. It is incumbent upon President Rouhani, given his role as the principal enforcer of the Iranian constitution, to assign a special representative to review the herasat’s activities, report directly to the president on the use or misuse of its powers and any violations, make specific recommendations aimed at reigning in the abuses committed by the herasat, and follow through on the implementation of these recommendations.

Notices of constitutional violations

According to Article 113 of the Iranian constitution, the president of Iran is the highest official in the country after the Supreme Leader, and he is responsible for implementing the constitution. As the principle enforcer of the constitution, President Rouhani has not only the right but the responsibility to defend the rights contained therein and serve official notice to any branch, body, or institution of the government that has carried out practices in violation of the constitution. Such constitutional notices (formal presidential notifications of constitutional violations) are a vital mechanism to check constitutional abuses, drawing public attention to and calling on violating organizations to cease their violations.

For example, the Islamic Republic of Iran’s Broadcasting organization (IRIB) routinely broadcasts show trials and forced confessions of prisoners that have been elicited through torture, and produces documentaries that have defamed, libeled, and facilitated the illegal prosecution of Iranian citizens, without extending them an opportunity to defend themselves. This is a clear case where it is incumbent upon the president to serve a constitutional notice to IRIB that they are violating the constitutional rights of Iranian citizens contained in Article 37 (which states that innocence is to be presumed, and no one is to be held guilty of a charge unless his or her guilt has been established by a competent court) and Article 38 (which states that all forms of torture for the purpose of extracting confession or acquiring information is forbidden), and that they must cease this practice.

The continued house arrest of political opposition figures Mir Hossein Mousavi, Mehdi Karroubi, and Zahra Rahnavard, who were never charged nor convicted in a court of law, is also in clear violation of the Iranian constitution. Article 34 states that all citizens have a right of access to competent courts, and Article 37 states that innocence is presumed until guilt has been established by a competent court. President Rouhani should issue a constitutional notice regarding the illegality of their arrest, publicly demand their release, and use all the powers of his office to put an end to such practices.

The president can and must launch investigations into all allegations of abuses and issue constitutional notices to any state organization that is violating the constitutional rights of Iranians. Moreover, he must demand that such organizations respond to the allegations and cease the violations, and inform the public of the results of such investigations, thereby fulfilling his responsibility to defend the constitution.

Many journalists and publications have faced lawsuits, arrests, detentions, shutdowns, and bans on publishing by officials for criticizing government organizations, particularly in recent years. This is in direct violation of the Iranian constitution, which states in Article 24, “Publications and the press have freedom of expression except when it is detrimental to the fundamental principles of Islam or the rights of the public.”

The Iranian president can use his authority to issue directives to all ministries under the executive branch to discourage government officials from filing lawsuits against newspapers for their criticism, and can use his office to encourage them to respond to the criticism rather than persecuting the critics.

According to Article 20 of the Iranian constitution, “All citizens of the country, both men and women, equally enjoy the protection of the law and enjoy all human, political, economic, social, and cultural rights, in conformity with Islamic criteria.” Yet in practice and in law in Iran, women face severe discrimination in such areas as education, employment, state benefits, family law, and court proceedings.

President Rouhani should fulfill his campaign pledges to uphold the rights of women and present legislation to Parliament that directly addresses discrimination against women in Iran.

For example, he can remove restrictions on the enrollment of female students in academic disciplines that have been imposed in recent years by the Ministry of Science, and issue an executive order to the Ministry of Science to end segregation policies that lead to discrimination against female students inside Iranian universities. The president should also present bills which end discriminatory divorce laws and address all other discriminatory aspects of family law in Iran. He should introduce legislation that makes women equal to men under the law. Extending public health insurance and state services to unemployed female heads of households is also a critical need of women in Iran.

In addition, the lack of female participation in high-level government positions (including the president’s own cabinet, which does not have a single female minister) is an issue that should be addressed. President Rouhani should actively promote the participation of women in senior government positions who will effectively pursue anti-discriminatory policies.

Discrimination in government employment practices

The government is a major employer in Iran, and as such, government hiring practices have a huge impact on the country. At present, there is severe religious and ethnic discrimination in government hiring practices in Iran. Religious discrimination most pointedly affects Baha’is and Christian converts: Iranian Baha’is are completely denied government employment, and converted Christians have to hide their faith or they will be expelled from government employment. In addition, ethnic Kurds, Arabs, and Baluchis face significant discrimination in state hiring practices. Provincial and local level government offices rarely hire citizens indigenous to the province in management and high-level positions, and these communities are thus cut off from an important source of employment as well as decision-making capabilities on the local governmental level.

The Iranian president can take direct action to address this discrimination, issuing an executive order forbidding discrimination against religious or ethnic minorities in Iranian government hiring. In addition, he can explicitly institute anti-discrimination government hiring codes. Moreover, the president’s Minister of the Interior appoints provincial governors, and thus the president can direct them to increase the hiring of local ethnicities in management positions, particularly in Kurdistan, Baluchistan, and Khuzestan.[1]

The encouragement of government transparency

At present in Iran there is a glaring lack of government transparency and a severe lack of reliable and timely government statistics. This dearth of information leads to a lack of government accountability and facilitates government inaction. Inaccurate or nonexistent information on such areas as the state of the country’s economy, corruption, and substance abuse and other public health issues impedes the government’s ability to address the country’s social and economic ills.

The president can and should develop policies to provide citizens, journalists, and academics with full access to unclassified government information, documents, and publications. He can issue directives requiring state organizations and units to provide regular, accurate, and timely information and statistics to the public on the activities of the government and on the state of the country. He should also require public access to transcripts of public sessions of all decision-making centers under his administration.

Download the full report here (PDF)