Background

Iran’s National Information Network (NIN) has emerged as the central plank of the Islamic Republic’s efforts to control its citizens’ digital access and communications.

The initial concept was to create a state-controlled and censored version of the global internet, originally called the “National Internet,” after which access by Iranian users to the global internet would be severed. Its purpose was to allow Iranians access only to state-approved content.

Yet officials realized that such an action was not technically feasible, as it would interrupt the activities of universities, banks, companies, government offices, police and many other organizations that would need to be connected to the global internet. Furthermore, even if it was possible to cut off Iranian users from the global internet and to issue special permits for certain organizations to be allowed access to it, it would be nearly impossible to administer and monitor their access.

As a result, the concept was withdrawn; what Iranian officials had referred to as the “National Internet” or the “Halal Internet” became the “National Information Network.” This National Information Network (NIN) is a state-controlled network on which Iranian users are able to use domestic (state-issued) facilities such as search engines and email services, conduct bank and trade transactions, and access content produced inside Iran, without having to use international services. Access to the global internet is possible, but users inside Iran must now go through the NIN to access the global internet. Critically, the NIN has allowed the state to separate international from domestic internet traffic. This has given the government the ability to cut off Iranians’ access to the global internet at will, while maintaining domestic access to the NIN—a capacity that was demonstrated, as previously mentioned, for the first time on December 30, 2017, when the government completely severed Iranians’ access to the global internet for a half-hour after unrest broke out across the country.

Since 2014 and concurrent with Rouhani’s presidency, phases 1 and 2 of the NIN have been launched. These phases have primarily concerned laying the technical groundwork for separating international from domestic internet traffic, keeping Iranian internet traffic inside the country, and providing the infrastructure for hosting content inside Iran.

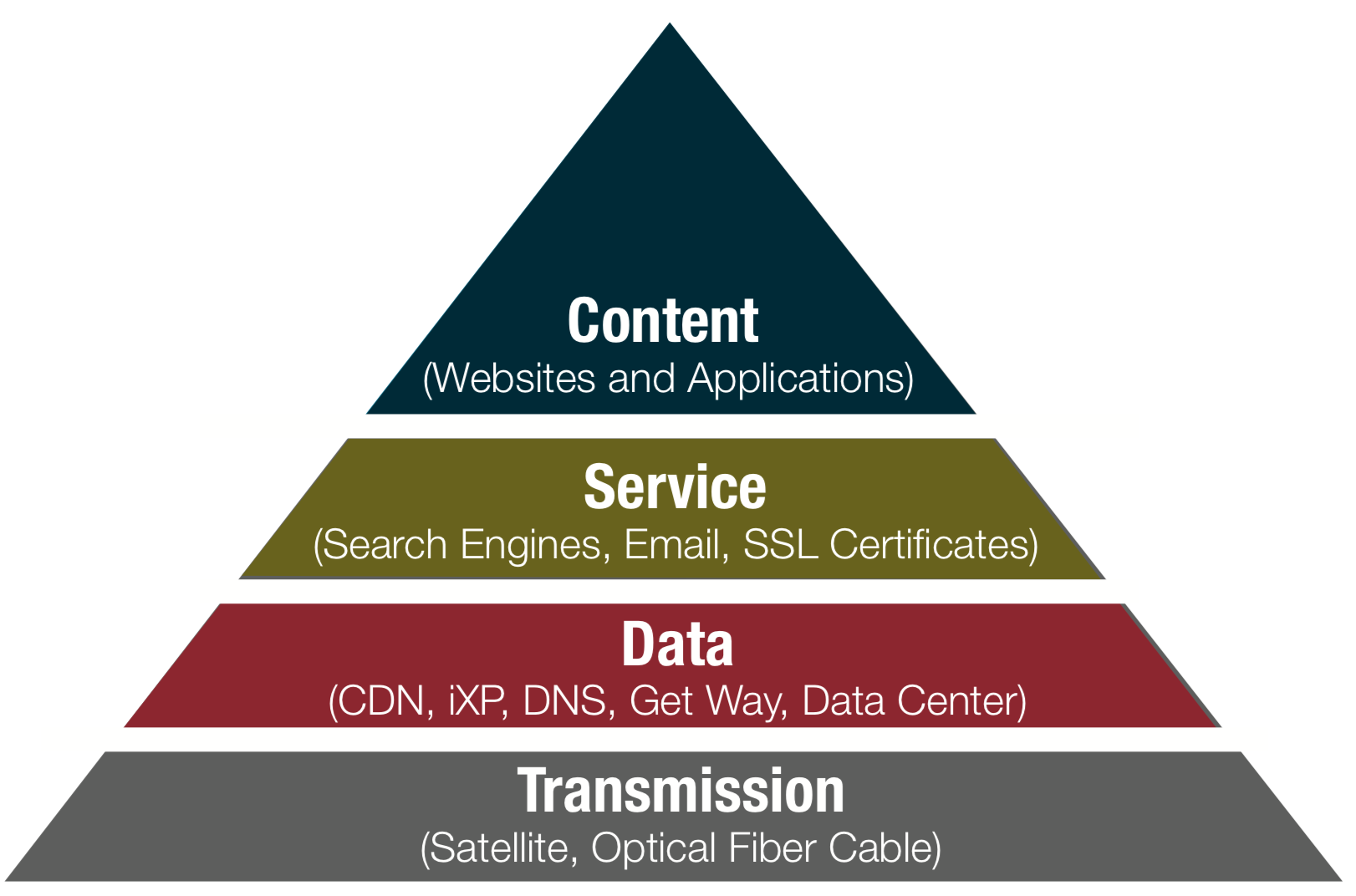

COMPONENTS OF THE NIN

The NIN is augmented by domestic services that mimic global online services (for example, a video service called Aparat, which is the NIN’s version of YouTube) that drive traffic to the NIN because the government makes them faster and cheaper for Iranians to use than the corresponding global services.

The increase in internet speeds, while promoted by Rouhani as central to the digital modernization necessary for the country’s economic and professional vitality, has also been integral to the success of the NIN. A little publicized aspect of the bandwidth increases has been the extent to which most of it has been funneled into the domestic connections used by the NIN. While internet speeds have improved across the board for both international and domestic internet traffic, and this has brought significant benefits for internet use throughout the country, the lion’s share of the increases has been used for faster internet connections for sites hosted inside the country.

The NIN has been sold to the Iranian public on the basis of government claims that it is cheaper, faster and more secure than the global internet. As will be detailed in this report, these claims are problematic and do not take into account the losses to Iranian users in uncensored access and online privacy.

While the cost of internet access has indeed been reduced and speeds have increased significantly, the NIN has also allowed state censorship to be implemented on a wider and more sophisticated scale, strengthened the state’s online surveillance capabilities, and enabled the state to disrupt or cut off Iranians’ access to the global internet. While it is yet to be determined if the NIN will provide its users with greater technical security from some types of hackers and digital threats, the NIN will make it easier for state security, intelligence, and judicial agencies to monitor, hack and disrupt citizens’ online communications.