Fake Applications

Another method used to intercept the communications of Iranian users is through the distribution of pirated versions or localized versions of popular applications that are widely used in Iran.

For example, the messaging application Telegram, which remains unblocked in Iran and has 40 million registered users there, has turned into one of the main sources of news and discourse among Iranians. Unlike other social networks, Telegram also enjoys high popularity among hardline and even radical groups, such as the Basij voluntary militia, and ultraconservative clerics and politicians. Indeed, even those who have held the most vehement stance against other social networks not only have their own news channels on Telegram, but have opposed its blocking.

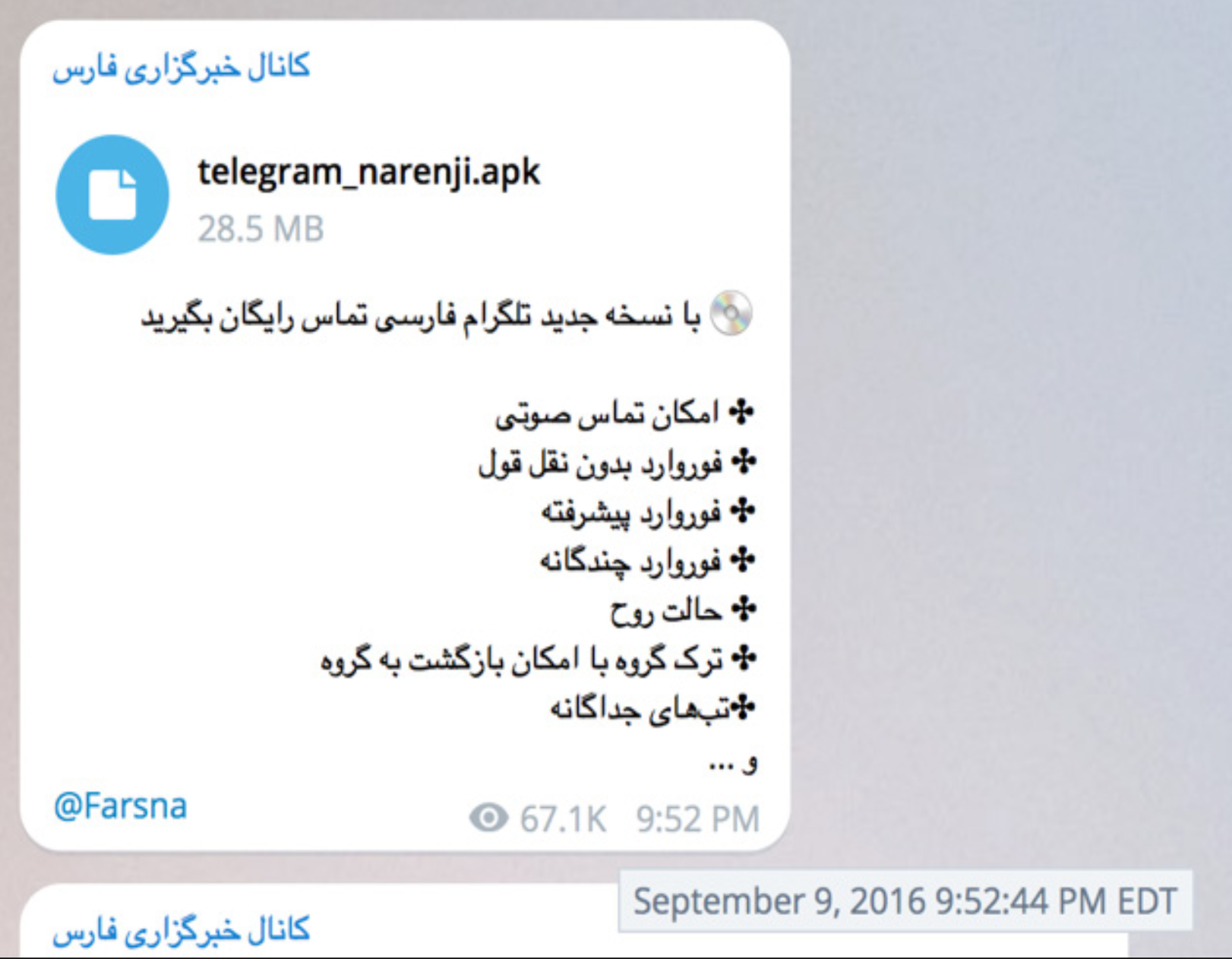

An example of Fars News Agency’s Telegram channel advertisements for Farsi Telegram

For example, Hasan Abbasi, a hardline ideologue who is close to intelligence agencies and has more than 21,000 members on his Telegram channel, appeared on a television program in November 2016, where he opposed the blocking of Telegram: “I am a member of Telegram. The legal issues, whether from a morality or a security stand point, remain. In our evaluation and overall assessment, the positive aspect has far outweighed the destructive security aspect…. The medium will come to our help and the [correct] ways of usage will be taught by the people.”

Cognizant of the popularity of such applications, state authorities have launched alternative (domestic) mobile social networks. The semi-official Fars News Agency,

for example, repeatedly introduced and promoted the capabilities of an alternative application named Farsi Telegram for a month in September 2016 on its Telegram channel. It is worth noting that Fars News Agency’s Telegram channel has, as of this writing, never advertised any other products or services and Fars News Agency never accepts advertisements for its Telegram channel or affiliate channels.

CHRI research indicates that Farsi Telegram is in fact a doctored version of the Telegram app in which other capabilities such as phone calls, with the help of open source programs, have been added and made available to the public. (When Farsi Telegram was introduced in 2016, the original Telegram had no voice call capability

at that time.) Yet unlike the original Telegram, Farsi Telegram has no encryption and if users use this application, not only would the content of their communications be accessible to intelligence agents, their phone conversations could also be tapped. Telegram CEO Pavel Durov addressed the issue of the compromised security of these fake applications in a tweet on July 29, 2017, in which he responded to another Farsi version of Telegram, Mobogram, stating, “Mobogram is an outdated and potentially insecure fork of Telegram from Iran. I don’t advise to use it.”

As servers for social media networks or popular foreign instant messaging applications are located outside Iran and Iranian security, intelligence, and judicial organizations have no control over them, over the past two years, Iranian officials have frequently spoken about the necessity of creating and encouraging people to use localized messaging services as an alternative to applications such as Telegram.

For example, on May 28, 2016, referring to a speech delivered by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, Seyed Abolhassan Firouzabadi, Secretariat of the Supreme National Security Council, said, “With the approval of this Council, localized online instant messaging networks which are competitive with foreign messaging apps will be launched within a year.”

As of yet such applications have been developed—but have attracted little user interest in Iran. Similarly, the authorities’ efforts to pressure foreign companies into placing their servers inside Iran have been roundly refused. The complete loss of user security either option would present has not been lost on the Iranian public, and international companies do not wish to lose their customer base.