Malware

Malware is a computer program that runs spyware with the aim of collecting information or eavesdropping on the victim after the spyware is installed on a computer or mobile phone. Malware usually allows the attacker to commandeer the victim’s computer without his or her knowledge. Malware attacks are heavily used in Iran to monitor, take control of, or block accounts.

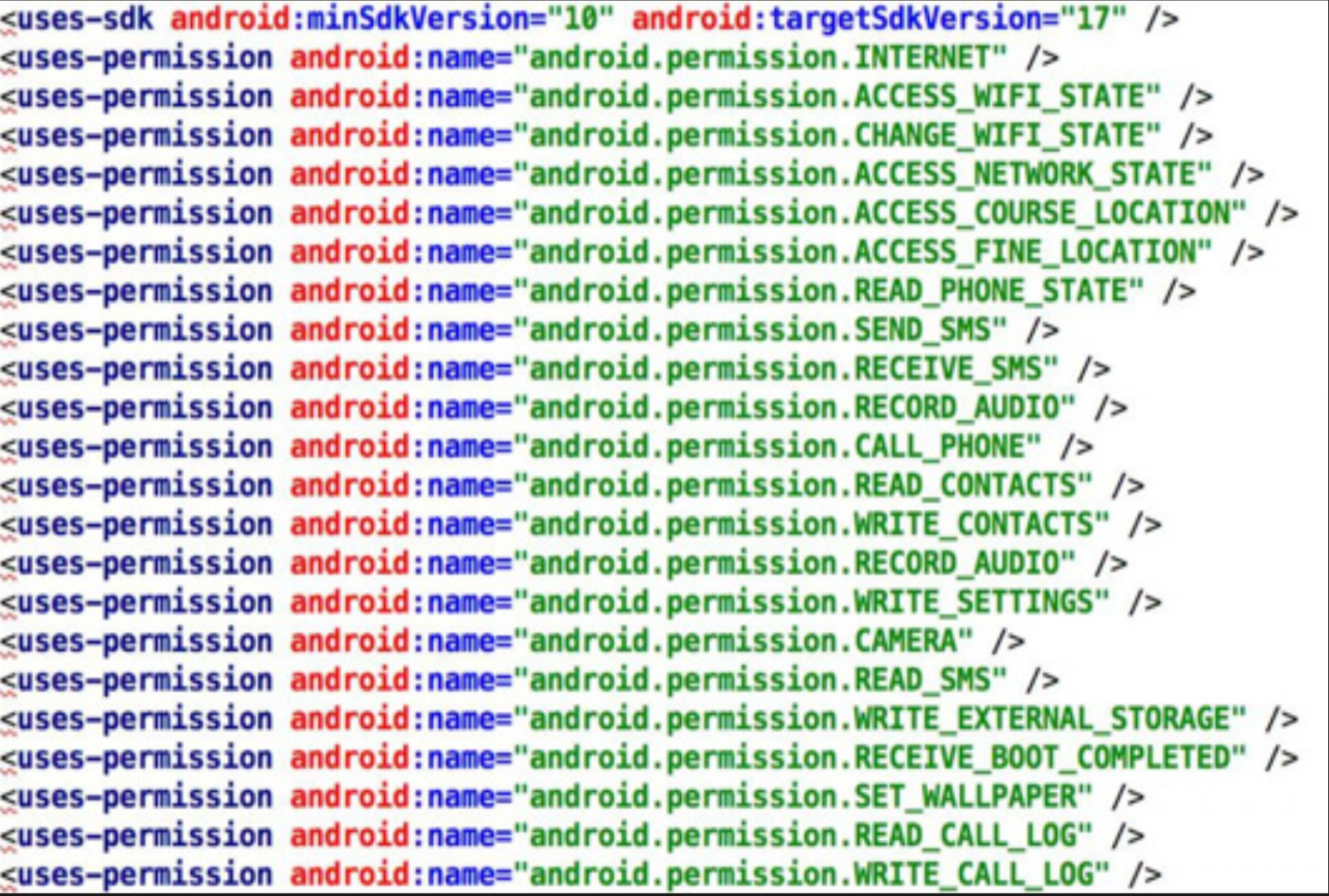

This image shows an Android malware analyzed by CHRI. This malware was used to attack a political activist in France.

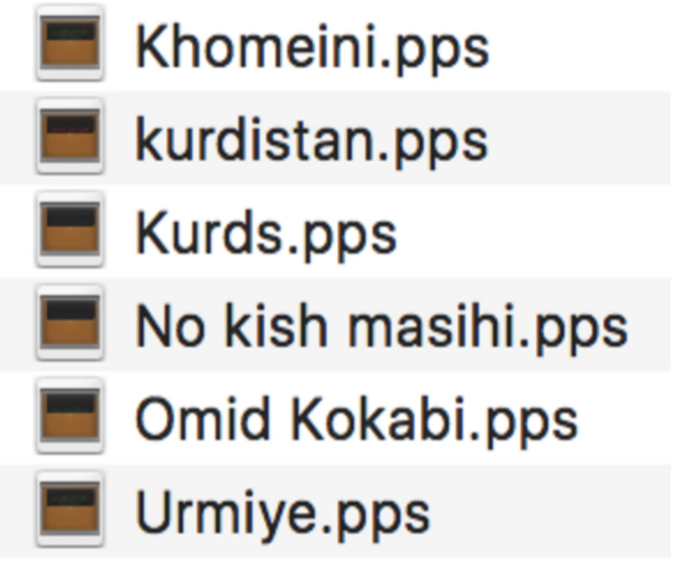

During the February 2016 Parliamentary elections, Hassan Khomeini, the (reformist) grandson of Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran, was disqualified by hardline vetting bodies from participating in the election. Immediately afterwards, an email containing a PowerPoint file was sent to journalists inside Iran, stating in the body of the email, “Urgent statement by Hassan Khomeini in reaction to his disqualification.” Considering the sensitivity and urgency of the subject to Iranian journalists, the hackers knew the file would be quickly and widely opened. As soon as the journalist opened the file, a program named Key logger was installed on the victim’s computer, which saved every key pressed on the keyboard and transmitted it to the hacker.

According to the Iran Threat’s website, which analyzes attacks by Iranian state hackers, there was only one malware attack in Iran prior to the Rouhani administration. Yet from April 2014 to May 2016, CHRI recorded dozens of examples of attacks using this method.

Examples of the PowerPoint files infected with the Key logger malware, received and investigated by CHRI.

Such malware is generally designed for the Windows operating system, although one example of such malware was also discovered for the Mac operating system. According to a report by the Iran Threats website, this malware, MacDownloader, was previously used to target other countries’ infrastructure but has more recently been used to target Mac computers belonging to Iranian human rights activists. MacDownloader steals the user’s computer password and creates a fake page where the user types in his or her password in order to enter the computer.93 It also introduces itself via two fake files for installing the Flash Player94 software and the Bitdefender95 Adware Removal Tool. After the user installs the malware, it hides itself in the computer and then makes copies of the database in Keychain Access.

Keychain Access is an application on the Mac OS that allows users to store data such as passwords for emails, websites, Wi-Fi connections, and hardware and software resources that are shared on the network, as well as encrypted disk images of computer memory.96 In this way, by making a copy of the database program, the hackers gain access to a large part of their victim’s information.

Malware is usually not detected by anti-virus programs because the process of finding, reporting and investigating malware by anti-virus companies, and then presenting updated versions of the anti-virus, is a time-consuming process. That, combined with the typical user’s lack of basic security knowledge, means that even before these stages are passed, the hackers have already accessed their victims’ accounts.

Even in instances where the malware is identifiable by anti-virus software, most users in Iran are using older versions of the anti-virus software and the software will no longer protect them against hacking. Remaining sanctions on Iran and Iranians’ difficulty conducting international financial transactions have further hindered their ability to download or buy updated software.

In addition to malware used by state-affiliated hackers to hack Windows and Mac operating systems, over the past two years there has been a substantial increase in malware designed to attack smartphones with the Android operating system, due to the rapidly increasing number of mobile phone users in Iran. After 3G and 4G services were made available to the Iranian public, smartphones and tablets became the main tools for web surfing in Iran. According to a report published on Donya-ye Eghtesad Newspaper on November 29, 2015, there are some 40 million smartphones in Iran. Such a broad market has attracted hackers.

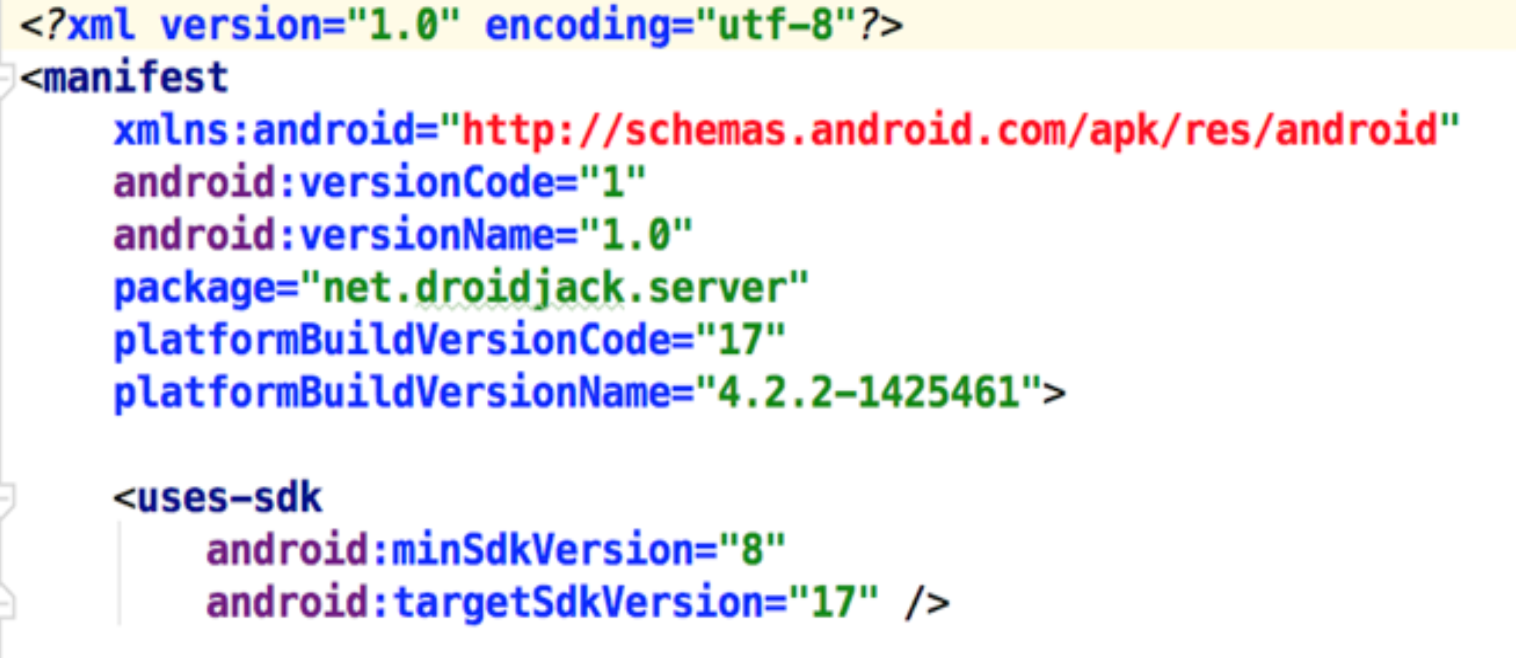

For attacking smartphones that use the Android system, hackers now often use tools widely available on the market (that were not intended for malware but can be easily subverted for that use), instead of writing new code to create the malware. According to CHRI research, hackers predominantly use tools such as Metasploit or DroidJack in this regard.

Since the Android operating system, unlike the iOS operating system, allows its users to install Android apps from sources other than certified sources such as GooglePlay, the hackers use different tactics to deceive their victims into installing a fake app that the hackers send.

In one example recorded by CHRI, the hacker told the victim that if he used the file sent to him, he would be able to create a safe audio visual connection.

This image shows the configuration files of the malware CHRI has analyzed. The malware targeted a prominent political activist in Paris. The malware was created using DroidJack.

In another instance, an unknown person contacted a prominent political activist living in France through Facebook and introduced himself as one of his “old students.” The hacker said the activist “had done a lot for him,” and as a token of his appreciation, he had built him some stickers with his picture for the Telegram application. He sent him a file with the APK extension that contained the picture. Fitting the victim’s photo into the file sealed the deception.

The victim’s picture was put in the malware file to deceive him.

In both cases, once the malware was installed, the victim’s phone became an online espionage device; every action the victim took was transmitted to the hacker. The hacker was also able to work with the victim’s phone. For example, he was able to send text messages, work with any of his applications such as Skype, and even open websites on his browser. The hacker was also able to read his emails and send email messages on his behalf.

All of the attacks using this method that were reported to CHRI targeted individuals such as journalists, civil activists, or political dissidents—in other words, perceived opponents of the state.