National Search Engines

HOW THE NIN’S SEARCH ENGINES REDIRECT USERS TO “FAKE NEWS” WEBSITES

With the development of the NIN, Iran’s national search engines now automatically block key words and phrases—and send users to sites that deliver only state-approved and sometimes fabricated content.

National data centers comprise an important part of the infrastructure of the NIN. These centers are responsible for data storage, maintenance and processing, and maintaining the space for hosting websites in the country, online email communications, domestic messaging services and all communications between government and non-government organizations and users inside Iran.

The data centers were privatized under the Rouhani administration, but again, the term private sector is imprecise in the Iranian context, including in the technology sector. Most ostensibly private companies are either at least partly state-owned or owned by parastatal parent organizations. Iranian officials have stated that foreign companies have expressed interest in participating in launching the data centers. Communications Minister Mahmoud Vaezi told Fars News Agency in February 2015, “In the post-sanctions negotiations, the Chinese company Huawei asked to build data centers in our country and Iran agreed with the request.”

The ownership and state affiliation of the Iranian companies connected with these data centers is unknown. This lack of transparency raises security concerns because it means the nature of the state’s continued involvement, if not control, is not known. Data centers play a central role in the maintenance of data for web hosting, email, and cloud processing, and are responsible for storing and protecting users’ online information and communications. Given the record of online surveillance and hacking by Iran’s security and intelligence organizations, any potential state involvement in or access to these data centers raises troubling security issues. Indeed, the aforementioned case in which state officials ordered a hosting company to delete the Memari News website’s content after it reported on corruption in the Tehran municipality bodes poorly for the security implications of these data centers.

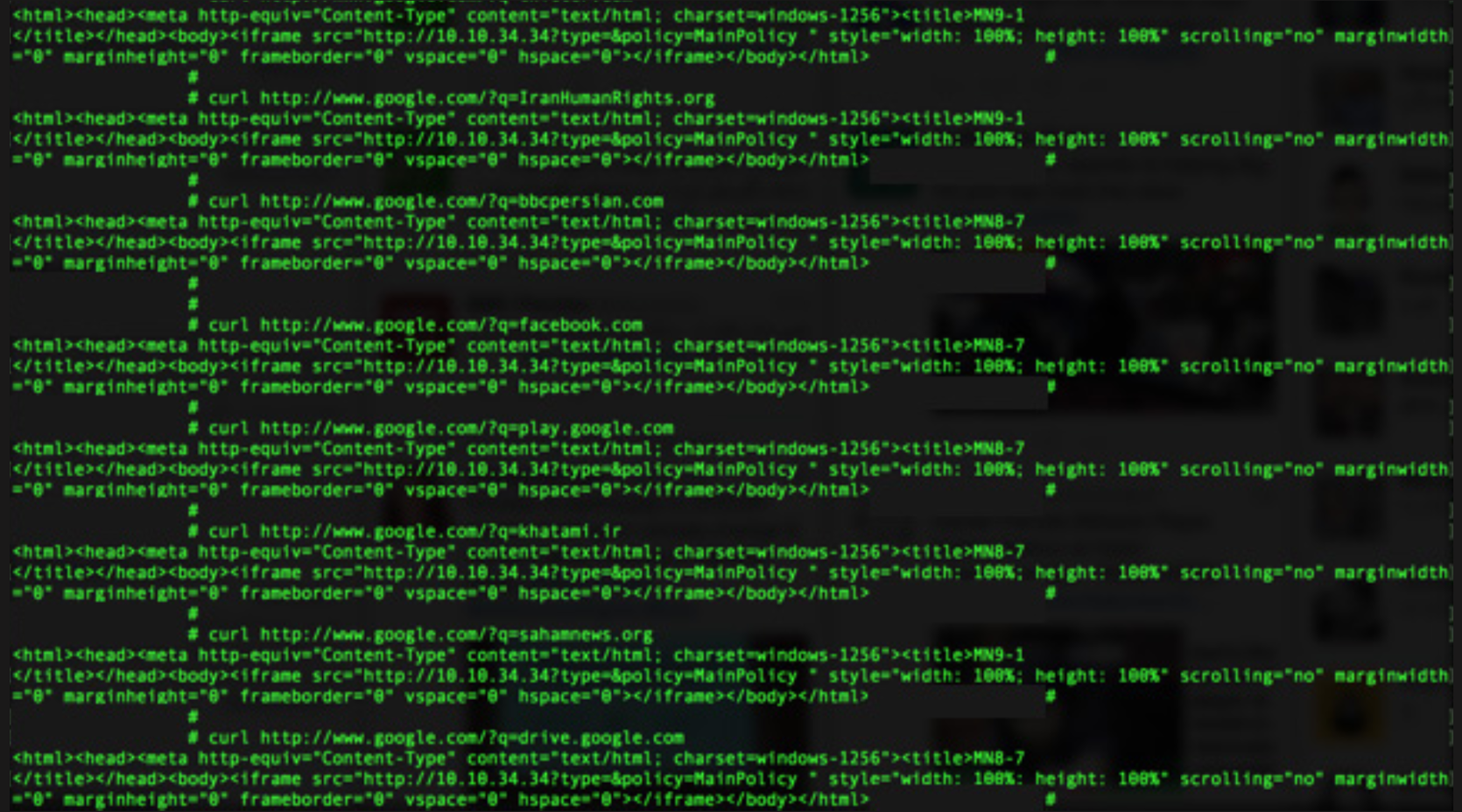

This image shows that without an SSL security certificate, the search results of news websites, social networks, and Google Play will direct the user to a filtering page.

Because of the difficulty in censoring international search engines that use encrypted web traffic, the Iranian authorities have intensified their promotion of the NIN and all its various auxiliary tools and services such as the national search engines. Iranians are bombarded continuously with advertising on state-run media that aggressively broadcasts the NIN’s pricing incentives, increased speed, and (supposed) safety benefits.

The reception in Iran nevertheless seems to remain less than robust. On March 2, 2015, Farhad Elyashi, a member of the Tehran Computer Trade Organization’s Software Commission said Iranian users will show no interest in using the National Search Engine. “There is this image that Iranian engines present content in a filtered fashion, leading to results that the user does not want and this is one of the reasons the Iranian search engines are not received enthusiastically,” Mr. Elyashi told Khabar Online, adding, “A search engine that presents only partial results will not be received well.”

The authorities appear to be intensifying the censorship attributes of the NIN. For example, Iran’s national search engines offer the user an option of “Intranet (NIN) Active/Inactive.” Previously, this gave the user a choice between conducting the search on the NIN (“Intranet Active”) or on the global internet (“Inactive”). If a user chose active, and searched for the website of reformist former Iranian President “Mohammad Khatami, who is now reviled by the Iranian government, the first result shown was a phony website linking Khatami to anti-US propaganda (“Mohammad Khatami’s election website in the US”). The former president’s website was not displayed in subsequent search results, either. If the same phrase was entered on the Google Search engine, the first result would be Khatami’s actual website. Yet as of October 2017, the choice is no longer offered; selecting either Active or Inactive produced the same search result for Khatami: the bogus website.

Ministry of Communications and Information Technology officials have consistently denied the specific state filtering and deletion of content related to human rights or sensitive political issues. Nasrollah Jahangard, deputy minister of CIT told ISNA on February 24, 2016, “The politicized atmosphere has led us to consistently accuse Iranian software programs of … filtering.”

Yet CHRI research does not support Nasrollah Jahangard’s comments. Searching for the names of civil activists or political prisoners, or topics such as the disputed 2009 presidential election, the serial killings of dissidents abroad during the 1990s, the mass executions of prisoners in the 1980’s, or the financial corruption of current state officials, will all confirm that blocked information and state censorship remains robust in Iran. In effect, the national search engine provides a world parallel to the real world for Iranian users, in which only hand-picked information in support of the state narrative of events and individuals is delivered.

This image shows that Parsijoo search engine, which has been introduced as the “National Search Engine,” provides forged and false information to the users.

Iran has also tried to encourage international companies that provide search engines to implement Iran’s censorship policies in their search engine results. Alireza Yari, secretariat of the Steering Council of National Search Engines, said in September 2012 that they had sent letters to Google, but had not received a response from the company.

In a state visit to Russia in November 2015, Mahmoud Vaezi, then minister of communications and information technology, announced that according to an agreement signed with Russia, the developers of the Russian search engine Yandex would soon open an office in Iran. At the time of the announcement, access to the Yandex search engine was blocked in Iran and as of April 2017, no changes have been made in this area.

The Iranian government has spent large sums on the devlopment of its national search engines. The failure of a number of them has not deterred continued investment, reflecting their perceived importance to the state’s censorship efforts. For example, Gorgor, a search engine introduced as the national search engine in 2015, is no longer active and no official has ever offered any explanations for its quiet disappearance despite the resources that were allocated.

The model used to guide user search results on the NIN is one of the costliest and most sophisticated applications of its kind and the implementation of this policy by government ministries is in stark contrast to numerous public statements made by President Rouhani defending the right to access information. In fact, during Rouhani’s presidency, the ability to manipulate the way content is presented in search results

in order to achieve engineered results, a long-standing dream of opponents of free access to information, has become a reality.

The Iranian government’s success in encouraging people to use the NIN will mean that in many areas—political, business, cultural, economic, scientific, social and even entertainment—Iranian users will be presented with filtered content, propaganda and intentional falsification by Iranian intelligence and security organizations, rather than real information.

Prior to the launch of the NIN, the state-run Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting organization (IRIB) was bestowed with this responsibility. Yet during the past decade, the IRIB has lost influence, credibility and power, as satellite television networks based outside Iran and the internet have broken its monopoly on information. In his letter appointing Abdolali Asgari as the new head of the IRIB, Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei advised him to have “an effective presence in cyberspace,” reflecting the importance of the internet to Iran’s highest official.82