Rouhani’s influence

Despite the more marginalized role of the president and his ministries, the implementation of internet policies, if not the policy making itself, remains in the hands of the Ministry of Communications, which is under the authority of Rouhani. Hence on several occasions, he has been able to directly intervene and prevent the implementation of policies with which he disagreed.

For example, on May 6, 2014, through a direct order to the Ministry of Communications, and in opposition to an earlier decision by the Working Group to Determine Instances of Criminal Content to block the messaging application WhatsApp, Rouhani successfully had the ban reversed.

The Rouhani administration’s efforts also led to the removal, in May 2014, of limits on internet speeds over 128 kbps. Previously, nothing faster that 128 kbps had been allowed. These slower speeds had hampered Iranian civil society, rendering the internet largely useless for transferring the large files often used by activists and journalists.

Rouhani had long asserted the need to address the issue of internet speeds in the country. For example, In May 2014, Rouhani said at the Fourth Annual Festival of the ICT, “I, as president, am not happy with the bandwidth conditions in the country. We have reached an agreement with the Ministry of Communications and Information Technology to as soon as possible, to make third and fourth generations of broadband width available not only for homes and commercial centers, but also for cellular phone users, and to use the capacity of the private sector in the best way possible to this end.” Rouhani’s lifting of these limits was framed within the context of the broader modernization of the country’s information and communications technology infrastructure, but the benefits to internet access and use by civil society were significant.

Yet even in the areas of implementation, as opposed to policy, Rouhani has had to push to affect policy—receiving significant resistance along the way. On the bandwidth issue, for example, hardline critics of Rouhani argued that the issue is not within the president’s jurisdiction. In a May 2014 article, the conservative paper Kayan wrote, “The Working Group to Determine Instances of Criminal Content is responsible for determining the issues and protecting the people’s interests, which falls in the area of the judiciary’s responsibilities and if [Rouhani’s] statements are to be regarded as instructions, it would represent intervention in other branches’ affairs and is in violation of Article 57 of the constitution.”

As bandwidth is well within the technical implementation role still afforded to the administration, the criticism illustrates the increasingly sharp struggle within the state for control over the internet in Iran. Indeed, the internet has emerged as one of the central battlegrounds within the state, both because of its importance in controlling the citizenry’s access to information, and the divergent views between the Rouhani administration, which sees it as central to the modernization of the country, and hardliners, who see it as a threat to their control.

Ahead of Iran’s February 2016 parliamentary elections, the Rouhani administration came under pressure by the Working Group to Determine Instances of Criminal Content and the Iranian judiciary to shut down the popular Telegram instant messaging application. The messaging app, now used by some 40 million Iranians, was being used heavily to promote reformist, centrist and pro-Rouhani candidates. The administration was able to successfully oppose these attempts.

Rouhani’s Minister of Communications Mahmoud Vaezi said on February 26, 2016, “We have had a lot of discussions at these meetings. Some agencies put a lot of pressure [on the council] to disrupt the internet in the run-up to the elections, or to block certain social media, but we opposed it.” The messaging app, now used by some 40 million Iranians and all political groupings in the country, was particularly important to groups promoting reformist, centrist and pro-Rouhani candidates, as these groups cannot use the state-controlled broadcasting and print outlets available to hardline groups and candidates.

Yet reflecting the constant tug of war over the blocking of such platforms, in April 2017, on the threshold of the country’s presidential election, the Rouhani administration was unable to stop the blocking of Telegram’s popular Voice Call feature ordered by the country’s judiciary.

More recently, during the unrest that broke out throughout Iran in late December 2017, Instagram and the messaging app Telegram, widely used by the protesters, were quickly blocked, as were access to VPNs and other circumvention tools.

Since his first campaign for president in 2013, Rouhani has publicly supported greater internet access for Iranians. In May 2014, for example, he said, “We ought to see [the internet] as an opportunity. We must recognize our citizens’ right to connect to the World Wide Web,” as quoted by the official IRNA news agency. While seemingly tame, such remarks were delivered in a context in which supreme leader Khamenei was stating that the internet is “used by the enemy to target Islamic thinking,” and officials such as Deputy Prosecutor for Cyberspace Affairs Abdolsamad Khorramabadi were saying, “Foreign cell phone messaging networks such as WhatsApp, Viber, and Telegram… [provide] grounds for widespread espionage by foreign states on the citizens’ communications [and] have turned into a safe bed for cultural invasion and organized crime.”

Public expressions of support and isolated unblocking notwithstanding, Rouhani’s overall record on internet access has not been impressive, and on internet security it has been extremely poor, as will be discussed in greater detail in the filtering and cyberattacks sections of this report.

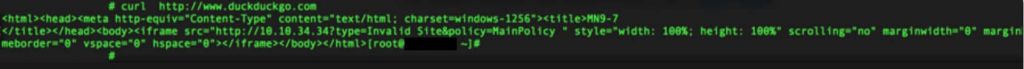

During his first term (2013 -2017), for example, at least 25 different tools that could provide users with secure online communication and browsing capabilities were blocked by the state. Over the past three years, access to secure messenger tools such as Signal and Crypto.cat, and the secure, privacy-friendly search engine Duckduckgo, have also been filtered and made inaccessible to Iranian users. In addition, major social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and YouTube all remain officially blocked in Iran, and the Rouhani-appointed Minister of Communications Mahmoud Vaezi admitted that the Ministry of Communications had filtered “seven million” websites during Rouhani’s first term.

This picture shows that the request to open the DuckDuckGo search engine without an SSL certificate leads the users to the filtering page, therefore Iran has filtered this search engine.

Perhaps most significantly, Rouhani has also not sought to hinder development of the NIN, even though its development has enabled the state to more effectively filter online content, monitor and access users’ online communications, and, critically, disrupt or cut off Iranians’ access to the global internet—a capacity demonstrated for the first time on December 30, 2017 after widespread street protests broke out throughout Iran. In fact, development of the NIN has accelerated under Rouhani, and state policies promoted during his tenure have aggressively encouraged Iranian users to use the sites and services of the NIN, such as its national email and messaging applications developed to replace Telegram and other encrypted apps.

Rouhani has also kept silent during his tenure on illegal activities such as cyberattacks against political and civil activists, journalists and even his own cabinet members. Article 25 of the Iranian constitution states: “The inspection of letters and the failure to deliver them, the recording and disclosure of telephone conversations, the disclosure of telegraphic and telex communications, censorship, or the willful failure to transmit them, eavesdropping, and all forms of covert investigation are forbidden, except as provided by law.”

Yet Rouhani, despite his promulgation of a Citizens’ Rights Charter, has made little if any effort to protect the citizenry in cyberspace, or attempt to explicitly extend the legal framework to protect digital communications. The NIN, which facilitates state access into accounts, and which, in all likelihood, will be used to facilitate the covert state surveillance of individuals, is a direct violation of citizens’ rights.

In sum, Rouhani’s record is decidedly mixed: his ability and/or willingness to extend political capital has varied considerably on internet issues. He has verbally defended internet freedom on numerous public occasions, unblocked some social networking platforms on a few occasions, and upgraded Iran’s ICT infrastructure to enable greater internet speed and use. Yet he has also allowed extensive filtering and social media blocking to continue, has overseen the accelerated development of the NIN, which, as discussed, has given the state the demonstrated capacity to cut Iranians off from the global internet (in addition to enhanced online surveillance capabilities), and, as will be discussed, has presided over a notable increase in state-sponsored cyberattacks without public comment. This, despite his pledge, as late as summer of 2017 during the announcement of his new cabinet members, that his administration would not filter the internet. Overall, Rouhani’s actions have fallen well short of his rhetoric. He has not protected Iranians’ right to access information or their right

to online privacy, actions that have left the people of Iran vulnerable to internet disruptions and cut-offs and to state intelligence and security agencies that can access users’ private online communications.