Speed and Bandwidth

One of the main objectives of the first and second phases of the NIN was to increase bandwidth in Iran. Until recently, internet service providers were not allowed to offer speeds faster than 128 kbps to home users. The removal of this constraint, advocated by and achieved under the Rouhani government, has enabled providers to offer services at higher speeds.

Undertaken simultaneously with this has been the segregation of internal and external network traffic. This segregation means that if users request access to content within the country and within the NIN, they will be able to use the faster (domestic) path, as opposed to the one they would have to use to access content outside the country. This has allowed the benefit of higher access speeds and lower costs for domestic traffic.

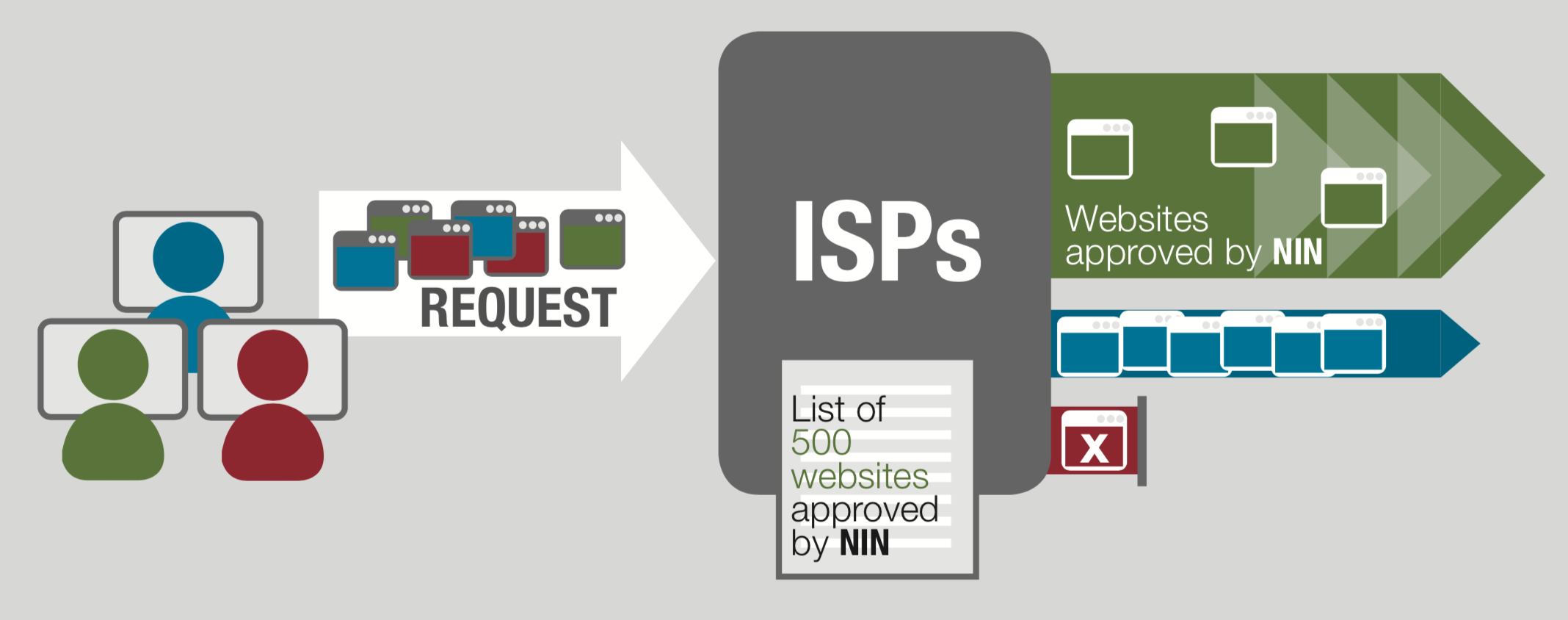

Three results can occur if a person tries to access a website while using NIN. If the website is filtered, the user will be denied access and directed to a filtered website notice page. If the website has been approved by NIN, the user will be able to access it at a discounted rate and at a faster loading speed. If the website is not filtered, but is not included on NIN’s “approved” list, the user will gain access at the regular speed and price

Mohammad Ali Yousefizadeh, the managing director of Asiatech Company, one of the largest internet service providers in Iran, told Mehr News Agency on March 11, 2017, “Currently, more than 200 internal websites with the highest traffic are accessible at half the price of international internet access.” This number has now increased to 500 domestic websites.

For example, the Asiatech, Rightel, and IranCell companies signed an agreement with the Communications Infrastructure Company whereby users who visit national websites such as Aparat, Filimo, Telewebion, and RazavaTV (which provide live broadcasts of the Shrine of Imam Reza in Mashad), will pay access rates that are 50-100% lower than their normal rates.

When users access websites outside the country however, the access rates have not been similarly reduced. Faster speeds and lower costs for domestic content are central to the state strategy to steer user traffic to the NIN.

By favoring domestic traffic, Iran violates the principles of net neutrality, According to the Global Net Neutrality Coalition, “To guarantee freedom of choice and information, net neutrality promotes the idea that internet traffic shall be treated equally, without discrimination, restriction or interference regardless of its sender, recipient, type or content, so that internet users’ freedom of choice is not restricted by favoring or disfavoring the transmission of internet traffic associated with particular content, services, applications, or devices.”

The Iranian government is violating net neutrality by segregating the internet into global and domestic networks for the purpose of offering higher speeds and lower rates for those who access domestic content. Disregarding net neutrality could potentially lead to the violation of the rights of online users and endanger their privacy because it enables the state to monitor private traffic and determine what sites users are accessing. Monitoring traffic should only be carried out under the law.

Iran’s Cyber Crimes Law makes several references to access to user traffic, and it prohibits eavesdropping. Articles 1, 2 and 3 ban “unauthorized” access or surveillance of online data. Violations carry a punishment of one to three years in prison or a fine. However, the law does not define authorized access.

In the US, federal laws restrict network monitoring to “headers” information, which only describes IP version, total Length of IP packet, source and destination address and other non-sensitive information. In his June 2017 statement, UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression David Kaye said repressive governments “are shutting down – or demanding that third parties shut down – services, including in times of public protest and mass dissent. Many are demanding that service providers retain and share user data. Still others are rolling back much-needed protections for net neutrality.”

Iran’s second largest mobile network service provider, Irancell (MTN), admitted on May 1, 2017, that VPN users won’t qualify for the 50 percent discount on monthly internet costs offered to those who limit their usage to 500 sites on the NIN. Other mobile and web service companies have followed suit. Offering these discounts

to discourage Iranians from accessing banned sites fundamentally violates net neutrality, which requires that “a maximally useful public information network aspires to treat all content, sites, and platforms equally.”

The objectives of the second phase of the NIN are to provide the average internet access speed of approximately 2 Mbps in third generation mobile telephones (3G), approximately 12 Mbps in fourth generation (4G), and approximately 5 Mbps in household DSL networks.46

According to a report by M-Lab website, which collects and analyzes more than 200 million tests of internet speeds worldwide, between 2013 and 2017 Iran’s internet speed for international traffic escalated from 0.3 Mbps to approximately 1 Mbps.47

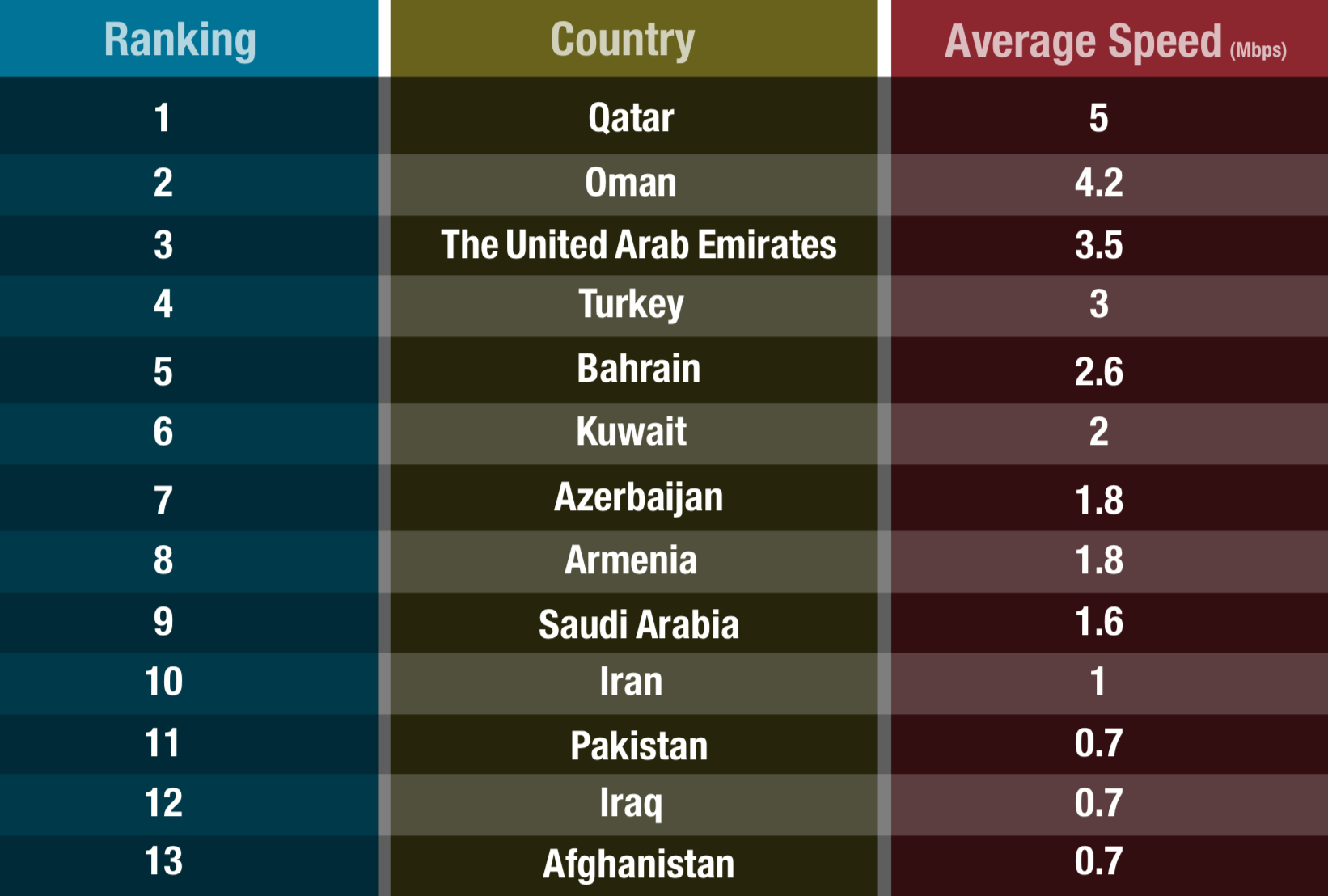

Although Iran’s international internet bandwidth has more than tripled over the past four years, this improvement is still less than the average internet bandwidth compared to countries in the region such as Turkey, with 3 Mbps, and the UAE, with 3.5 Mbps. The table below compares the bandwidth of Iran’s 12 neighboring countries based on M-Lab website reports:

Source: M-Lab, www.measurementlab.net

For mobile phones, internet speeds have also significantly improved. Mobile phones are increasingly central to Iranian online use: According to the Mehr News Agency, as of June 20, 2016, about 22 million Iranians use mobile internet—far more than home internet users.48 (ADSL internet users in the same period were nine million.) Between 2013 and 2017, the average internet speed for mobile phones increased from 0.2 to 2.4 Mbps due to the availability of 3G and 4G mobile services.

Additionally, during the same period, the Rouhani administration ended the Rightel Company’s monopoly over 3G and 4G mobile services, enabling other mobile phone service companies to offer these services to their users.49 Nevertheless, mobile users still face the same environment as that of home users, with faster speeds and lower prices steering users to state-controlled domestic sites.