Blocking under Rouhani

The Rouhani administration’s record on blocking sites has also not supported his stated support for internet freedom. To be sure, his administration has on several occasions resisted the blocking of social networks. For example, as previously mentioned, in 2014 Rouhani issued an order to ban the blocking of the WhatsApp messaging application, and, in the run-up to the February 2016 Parliamentary elections in Iran, he refused requests by police and security forces to block popular messaging services such as Telegram. (During those elections, pro-Rouhani, centrist and reformist political channels were prominent on Telegram.)

Overall however, the blocking of services and applications has quietly accelerated under Rouhani, and this has had significantly negative implications for online security in Iran. During his first term, many secure messaging applications and secure search engines were filtered and made inaccessible to users (see list below). The authorities provided no explanations for the blocking of these services.

Critically, the bulk of the restrictions have been imposed on tools for maintaining digital security and privacy, such as the aforementioned applications that provide encryption by default, enabling users to store and carry out correspondence, searches, and files in a safe environment.

For example, the DuckDuckGo search engine, which is an open source search engine widely regarded as a secure tool for maintaining the privacy of its users, was filtered and blocked during Rouhani’s first term.

Some of the other major sites filtered during Rouhani’s presidency have included security websites, messaging apps, search engines, and online games. They include:

- Signal secure messaging application

- Popular game Pokémon GO

- Google Play App Store

- CryptoCat secure chat application 5. Kik messaging application

- DuckDuckGo secure search engine

- Periscope video broadcasting tool on Twitter 8. Google Drive

- Netflix

- Russian search engine Yandex

- The Omid List website (which contained a list of reformist candidates for Iran’s Parliamentary elections)

- Dropbox file sharing website

- Website of author Mohammaed Ghaed

- Pinterest website for photo sharing

- Bitly link shortening website

- Steam comunity marketplace for computer games

- Origin marketplace for computer games

- Footballitarin sports website

- Imo messaging app

- Wechat messaging app

- Quora.com question and answer website

- Euronews’ news website http://persian.euronews.com was filtered, which was later changed to http://fa.euronews.com and the present address is not filtered.

- The movie db film poster website

- Blogger and Blogspot, Google Company blog services

- One Drive

As stated previously, the use of SSL security certificates makes it impossible for the filtering system to “read” the content, allowing many of the sites listed above to remain accessible despite being blocked. As a result, many observers have underestimated the extent to which filtering has continued and even accelerated under the Rouhani administration.

For sites focused on areas in which the authorities in Iran are extremely sensitive, such as human rights organizations (for example, CHRI) or social media networks widely used by activists and critics of the government (such as Facebook), the government institutes a more technically sophisticated blocking mechanism that the SSL cannot circumvent, based on the website IP address and TLS inspection. In this manner, such sites remain blocked in Iran, despite their use of an international SSL certificate.

The Working Group to Determine Instances of Criminal Content has also barred Iranian mobile app stores from offering applications to the public that are blocked

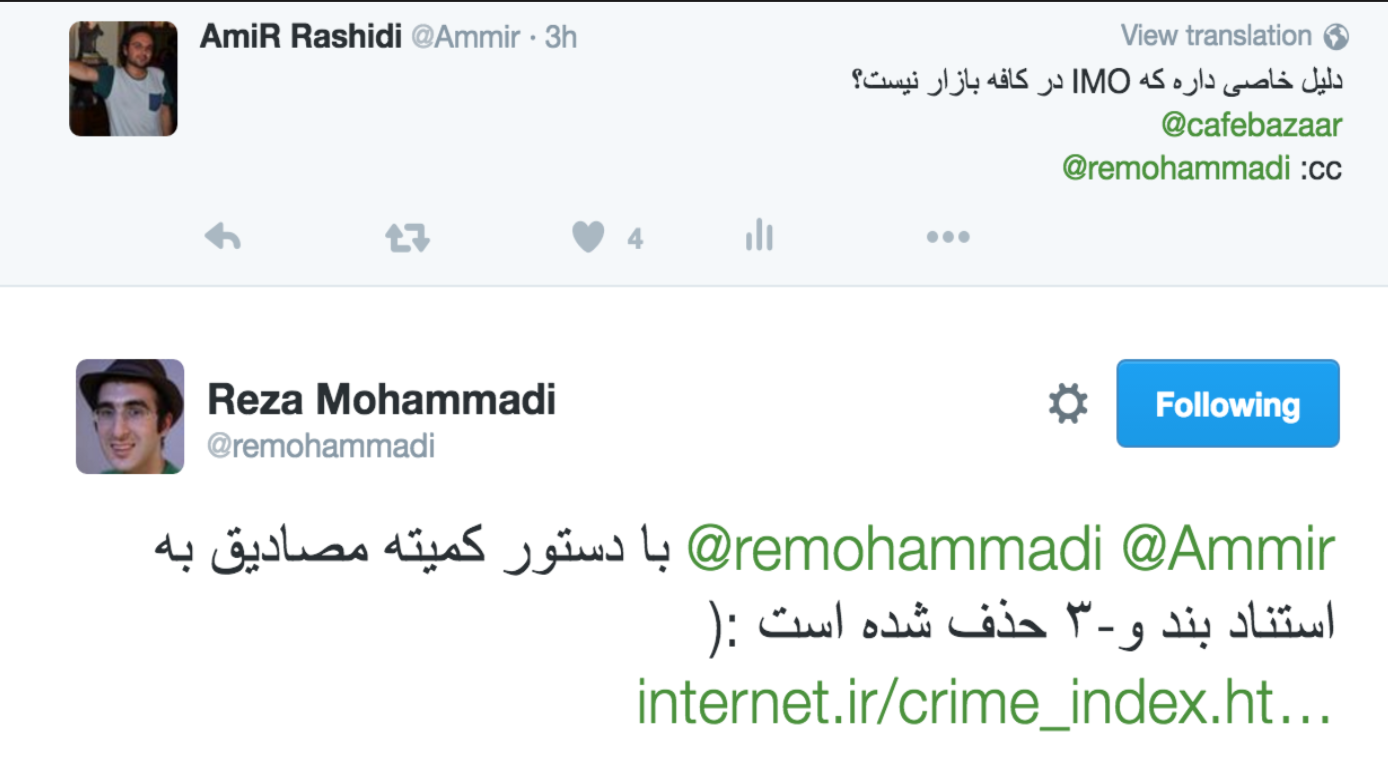

in Iran. For example, Reza Mohammadi, the Technology Department Head of Cafe Bazaar, the most popular Android app store in Iran, said in a tweet that the IMO app had been removed from the online store’s list by order of the committee, referencing the third paragraph of the Law on Cyber Crimes.

Reza Mohammadi, Technology Director of Cafe Bazaar, said in response to a tweet: The IMO application was removed from Cafe Bazaar on orders from the Committee to Determine Instances of Criminal Content.

According to this paragraph, “publishing links or promoting filtered websites or re- publishing criminal content of banned publications and media affiliated with groups and deviant and illegal organizations” is against the law and banned. In accordance with this law, none of the other popular blocked applications such as Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, or secure messaging apps such as Signal, are available for sale in Iranian stores.

Moreover, during important periods such as elections in Iran, filtering and blocking has increased. For example, during the run-up to the February 2016 Parliamentary elections, a video made by reformist former Iranian President Mohammad Khatami published on the Aparat website (announcing his support for reformist candidates) was removed on orders from the Committee to Determine Instances of Criminal Content, which cited Article 23 of the Law on Cyber Crimes.

Article 23 does not refer to content and only states, “Providers of web hosting services shall upon receipt of instructions from the working group that determines the instances mentioned in the above article, or the judicial authority reviewing the case for existence of criminal content in its computer systems, bar access to it” and in case of disobedience, they will face cash fines and a ban on activities.

Also during the February 2016 campaigning, content filtering on Instagram was more aggressive, via identifying user accounts, keywords and hashtags. Numerous user accounts which contained content concerning human rights or political activities were blocked. For example, access to hashtags that contained the names of Seyed Hassan Khomeini (the reformist grandson of the founder of the Islamic Republic of Iran Ruhollah Khomeini), former reformist President Mohammad Khatami, and centrist former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani were blocked, as were the hashtags referencing political prisoners such as #freejason, #jasonrezaian and #freearashzd.

During this period, the Omid (Hope) website, which provided a list of reformist candidates, was blocked as well. After the February 2016 Parliamentary elections were over, all Instagram hashtags without SSL were filtered, but because the entire Instagram content is by default on SSL protocol, the filtering has not had an impact on it and images are displayed for the users.

In April 2017, weeks before Iran’s May 2017 presidential election, Telegram’s Voice Call was blocked, based on a judicial order that cited the “national security” implications of their encrypted connection. Also in April 2017, Instagram Live, which had been used heavily to broadcast reformist political events, was blocked, without explanation or official comment.