Banning of Films Continues under Rouhani Administration, 14 Movies Now Forbidden

Despite repeated statements made by President Rouhani regarding the need to allow more cultural freedoms in Iran, the banning of films in the Islamic Republic has continued unabated during his two-year administration.

The latest film added to the list of forbidden cinema came just last month, in July 2015, when the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, which is under the direct authority of President Rouhani, banned Rastakhiz. This brought to 14 the number of films that have not received permission for public screening in Iran since 2007.

Although most of these films were prevented from screening during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency (2005-2013), they have yet to be seen by the public two years after Hassan Rouhani replaced him.

The most frequent reasons for the bans include references in the films to the mass peaceful protests that followed the disputed 2009 presidential election in Iran, a highly sensitive subject in the Islamic Republic that hardliners continue to refer to as the “sedition,” and issues with what is perceived as actresses’ “poor” hijab (female attire).

On June 5, 2013, during his presidential election campaign, Rouhani promised he would “hand over the monitoring of cultural matters to the people,” and he questioned how any individual censor could fairly judge a film’s religious violations. Such remarks increased hopes that banned films would make their way to the cinemas if Rouhani was elected.

Statements in support of cultural freedom continued during Rouhani’s presidency. In a meeting with artists and cultural figures on January 8, 2014, he stated, “Viewing the arts as a security concern is the biggest mistake.” He went on to say, “If there is no freedom, true artistic creations would not be produced. We cannot create and produce arts on order. Any type of security atmosphere can nip arts in the bud.”

In June 2015, at a press conference marking the second anniversary of his election to office, in response to a question by a reporter about the widespread cancellation of concerts over the past year, Rouhani said, “In the cultural domain, we believe cultural affairs should be relinquished to the people of culture, and the atmosphere must be facilitated so that consumers and producers of cultural works can meet.”.

Nevertheless, the disputes between the Rouhani administration’s Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance and Iranian filmmakers have still not been resolved, and the films remain banned.

A number of the blacklisted films were initially shown at the Fajr International Film Festival in Tehran, and some were screened in cinemas for a few days before being pulled. The latest casualty, Rastakhiz, was banned on the day it premiered, even though 40 minutes of it was cut to receive a screening permit from the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance.

During the past two years, extreme positions taken by conservative Members of Parliament and hardline media, along with ultraconservative religious groups, have played a central role in preventing films from public viewing.

In September 2014, the Cultural Affairs Committee of the Iranian Parliament wrote a letter to the Minister of Culture and Islamic Guidance demanding he refuse screening permits for eight films that appeared to be sympathetic to the public “rebellion” against Ahmadinejad’s victory in the widely disputed 2009 presidential election.

“What we expect from the institution in charge of the film industry is to have the authority to carry out its decisions. The Ministry of Guidance gave a permit for the screening of my film [Khaneh Pedari (The Paternal House)] but then it was forced to pull it down after just two days, even though it was only being shown in a small cinema,” director Kianoosh Ayari told the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.

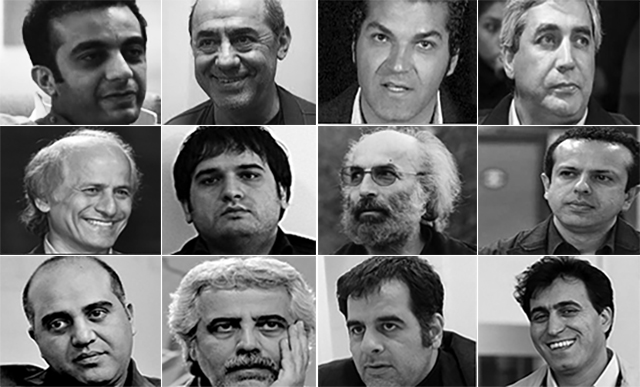

The Campaign has compiled the following report on 14 banned films. Other films may also have faced censorship issues but their makers have chosen to remain quiet, hoping to eventually get a screening permit.

RASTAKHIZ (Hussein, Who Said No), directed by Ahmad Reza Darvish

RASTAKHIZ (Hussein, Who Said No)

Rastakhiz (Hussein, Who Said No) opened in cinemas on July 15, 2015, but was pulled within hours because of criticism from conservative religious leaders and protests by religious hardliners in front of the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance.

Rastakhiz is a religious feature film set in 7th century Iraq that tells the story of the Ashura revolt, when Hossein, the Prophet Mohammad’s grandson and the third Imam of Shia Muslims, fought against the ruling caliph and died in an unequal battle near Karbala. Some religious leaders took issue with the depiction of Imam Hossein’s uncle Abolfazl al-Abbas. According to Shia theology, reproducing the face of the Imams and their family members is forbidden.

Director Ahmad Reza Darvish received many awards and accolades when Rastakhiz was first shown at the 2015 Fajr International Film Festival. But criticism from religious quarters was so strong that he was forced to cut 40 minutes of the film to satisfy Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance censors. Some religious leaders, however, were still dissatisfied and eventually forced the Ministry to pull its permit.

“As far as I’m aware as the director, this film has been made in accordance with the views of religious leaders, during the research phase when it received permission for production, and during the making of the film,” Darvish told ISNA, the official Iranian Students’ News Agency. “Even before public screening, when the film was being revised, representatives of some honorable religious leaders were present and some of them praised the filmmakers.”

According to the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance Spokesman Hossein Noushabadi, “Rastakhiz will remain in suspension until its issues are resolved. In any case, this film will be screened at cinemas. But we hope the esteemed director and producer will cooperate with us so that we can resolve the issues more quickly.”

It is unclear if Darvish has agreed to make more revisions.

KHANEH DOKHTAR (The Girl’s House), directed by Shahram Shah-Hosseini

KHANEH DOKHTAR (The Girl’s House)

The Girl’s House (2014), directed by Shahram Shah-Hosseini and written by Parviz Shahbazi, deals with issues facing Iranian women while telling the story of two female university students who try to solve the mystery surrounding the murder of one of their classmates.

Conservative media have slammed the film for being against “traditional and family values” and despite a number of revisions, it has not received a permit for public screening.

The Girl’s House was only screened at the 2015 Fajr Film Festival, after which it came under intense attacks from ultraconservative religious circles, and the Tehran Municipality’s cultural affairs division opposed its screening at cinemas under its management.

The state broadcasting organization IRIB (Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting) reported that “nearly all viewers” considered the film to be immoral and the conservative Fars News Agency (http://www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13931119000015) described it as an attempt to demonize religious Muslims and please foreign film festival judges.

Director Shah-Hosseini has dismissed the criticism. “I reject any accusation that this film is against Iranian or Islamic morals,” he told ISNA news agency.

MEHMOUNIYE KAMI (Kami’s Party) and MAADARE QALBE ATOMI (Mother of the Atomic Heart), directed by Ali Ahmadzadeh

MEHMOUNIYE KAMI (Kami’s Party)

Ali Ahmadzadeh has made two feature films in his young directorial career and both have yet to get screening permission. His first film, Kami’s Party, about a road trip by a group of youths, was rejected by censors because they thought the actresses did not cover themselves properly.

Mother of the Atomic Heart, Ahmadzadeh’s latest film, has failed to make it to the cinemas without any official explanation. But its title has fueled rumors that the ban is due to references to Iran’s nuclear program.

Despite problems at home, Ahmadzadeh’s films were well-received abroad. Kami’s Party won the Best Film Award at the third Festival of Iranian Films in Prague and Mother of the Atomic Heart was screened at the Berlin film festival.

A member of the production team of Mother of the Atomic Heart told the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran that censors have not explained why it has been banned. “What usually happens is that if a film has a chance of being screened after censorship and revisions, the monitors will discuss it in a meeting with the director. But there are some films which have fundamental problems in terms of plot, screenplay and production and for those the monitors will not even bother to set up meetings,” he added.

ASABANI NISTAM (I’m Not Angry), directed by Reza Dormishian

ASABANI NISTAM (I’m Not Angry)

I’m Not Angry premiered at the 2014 Fajr International Film Festival after director Reza Dormishian agreed to cut 17 minutes, including the final scene, of the film. But the film was also shown simultaneously at the Berlin Film Festival, with the final scene intact.

I’m Not Angry was widely praised by film festival audiences but the reaction by hardline MPs, state media and conservative pressure groups was quite the opposite, forcing officials to ban special screenings of the film and to cancel a promotional press conference.

Dormishian’s film is about a university student who gets expelled because of his political activities and struggles to control his anger. Hardline critics are particularly displeased with scenes showing the turbulent events after the 2009 presidential elections in a positive light.

Despite its popularity with the Fajr film Festival’s audiences, I’m Not Angry was pulled from the Festival’s competition category to ensure it received no awards, even though its leading actor Navid Mohammadzadeh had been nominated for the Best Actor award. At the awards ceremony, this note was read on behalf of the director: “Out of respect for the integrity of Iranian cinema and preserving peace, we will pass on our awards. Hoping for better days.”

BOLOOKE NOH KHOROOJIE DO (Block 9, Exit 2), directed by Alireza Amini

BOLOOKE NOH KHOROOJIE DO (Block 9, Exit 2)

Directed by Alireza Amini, the 2014 the Fajr International Film festival refused to show Block 9, Exit 2 because the organizers thought it was too “bitter”. Still, the film was screened at a number of foreign film festivals. Most recently it won Best Film and Best Actor awards at the Kimera Film Festival in Italy.

ASHGHALHAYE DOOSTDASHTANI (Lovely Garbage), directed by Mohsen Amiryoussefi

ASHGHALHAYE DOOSTDASHTANI (Lovely Garbage)

Lovely Garbage did not get permission for public screening when it was completed in 2012 during Ahmadinejad’s presidency. But director Amiryoussefi has still not been able to show his third film in cinemas because the censors are unhappy about scenes related to the disputed 2009 presidential election.

The film begins with a group of protesters demonstrating against the results of the election. They run away from the security forces and take refuge inside the home of an old woman. There they discuss and criticize events of the past 30 years.

“Despite the insistence of the producer and some politicians, this film has not received a viewing permit and there are no plans to screen it,” Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance Spokesman Hossein Noushabadi said in November 2014.

KHERS (The Bear), directed by Khosro Masumi

KHERS (The Bear)

The Bear (2011) tells the story of a prisoner of war who returns home after many years in captivity to find his wife has remarried. Although the film has undergone some revisions, it has not yet been released for public viewing.

“This film has not crossed any red lines. We even did some changes for the Fajr Festival,” director Khosro Masumi told the Aftab newspaper on November 30, 2014. “Despite our efforts, the film is still banned and it’s not clear why. This isn’t pleasant for the producer who invested in the film but I’m still hopeful The Bear will be screened.”

GOZARESHE YEK JASHN (The Report of a Party), directed by Ebrahim Hatamikia

GOZARESHE YEK JASHN (The Report of a Party)

The Report of a Party was nominated for several awards when it was first shown at the Fajr Film Festival in 2011. It depicts events at a matchmaking agency managed by a woman who is targeted by the police. But critics accuse director Hatamikia of hiding the film’s true message in support of those who challenged the validity of the 2009 election results.

In an unprecedented move, the state-owned Film Organization purchased the rights to the film in order to cover Hatamikia’s production costs, a favor shown to no other banned film in the past. Hatamikia has not commented on the film’s status.

“The Guidance Ministry owns this film and there are no plans to screen it,” according to Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance Spokesman Hossein Noushabadi.

KHIABANHAYE ARAM (Calm Streets), directed by Kamal Tabrizi

KHIABANHAYE ARAM (Calm Streets)

The leading character in Calm Streets is a reporter who is suddenly faced with events similar to the aftermath of the 2009 elections. Not surprisingly, it has yet to be shown in cinemas.

“I was pretty much sure that this film would be banned if officials lacked tolerance. There are certain sensitivities surrounding this film and according to what they have told us this film will not be screened for the time being, because it is somehow related to the 2009 incidents,” director Kamal Tabrizi told Borna news agency in August 2013.

PARINAAZ, directed by Bahram Bahramian

PARINAAZ

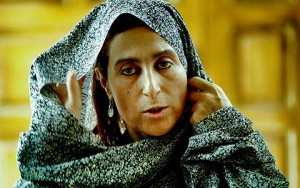

Bahram Bahramian’s second film is about a little girl who is raised by relatives after the death of her parents. The lead female character, played by Fatemeh Motamed-Aria, is a traditional woman who wears the chador, the full-body cloak.

“This woman is very religious and suffers from deep personal issues which cause problems inside the home. Although these issues get resolved at the end of the film, the cinema authorities have said that a chadori woman should never be shown with moral or psychological issues,” the film’s producer Abdolhamid Najibi said in an interview in July 2014.

After President Rouhani’s election and the arrival of new officials in charge of the film industry, Parinaaz was issued a screening permit but the film has still not been shown in public.

EEN YEK ROYA NIST (This is Not a Dream), directed by Mahmoud Ghaffari

EEN YEK ROYA NIST (This is Not a Dream)

This is Not a Dream, Mahmoud Ghaffari’s first feature film, was made in 2010. It is about a struggling young girl who gets caught up in a couple’s complex relationship.

“This is Not a Dream was sent to the 2013 Fajr Film Festival but after being shown to the selection committee, I was told it needed changes and I acted on their request. But even after the revisions, it was again rejected by the selection committee,” director Mahmoud Ghaffari told Mehr news agency on January 7, 2013.

KHANEYE PEDARI (The Paternal House), directed by Kianoush Ayari

KHANEYE PEDARI (The Paternal House)

The Paternal House received a screening permit in 2014, five years after it was first made. But after only ten showings at one theater in Tehran, it was pulled by the authorities.

Many have been critical of a scene where a fanatical boy brutally murders his sister with a rock. But veteran director Kianoush Ayari believes that is not the real issue behind the banning.

“The scene where the boy is ordered by his father to beat his sister with a rock only lasts a few seconds. That’s the only violent scene, which is nothing compared to similar scenes in other films which are screened without any problem in the cinemas. So it’s clearly an excuse. It looks like there are other interpretations which have caused this film to be banned,” Ayari told the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.

“It has been mentioned that this film has a tendency to reject Islamic behavior, but I don’t accept this view. That interpretation is completely wrong,” he added.

Ayari’s harshest critics have been in the Iranian Parliament. A day before the short-lived screening of The Paternal House on December 25, 2014, MP Morteza Agha-Tehrani, a member of the Cultural Affairs Committee said that MPs believed The Paternal House is unsuitable for public viewing and its permit should be revoked.

“It’s not right to attack our nation’s history with misguided ideas and [accuse] our forefathers of discrimination and violence against women,” Agha-Tehrani said.

SAD SAL BEH EEN SALHA (A Hundred Years Like This), directed by Saman Moghadam

SAD SAL BEH EEN SALHA (A Hundred Years Like This)

The main character in A Hundred Years Like This (2007), directed by Saman Moghadam is a woman named Iran who goes through many stages of life during a 30-year period. She first loses her husband in the 1979 Revolution, then her son in the Iran-Iraq war, and then other relatives who becomes victims of various social and political upheavals.

The references to the human cost of the Revolution and the establishment of the Islamic Republic have made authorities reluctant to release it to the public. As a result, its only screening was in the Fajr Film Festival in 2010.

“A Hundred Years Like This received a screening permit during the previous administration but there are no plans to screen it in this administration,” said Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance Spokesman Hossein Noushabadi in November 2014.