Hardliners Handpick Candidates to Block Moderates and Rig Elections

- 3000 reformist applicants (99%) disqualified for Parliament in first vetting.

- 63% of all applicants disqualified in first vetting, reduced to 40% in second round.

- Prominent ayatollahs excluded from Assembly of experts for their moderate affiliations.

- In most of Iran’s provinces, the Council handpicked the only candidates that could run for Assembly of Experts seats.

- None of the 16 women who applied to run for the Assembly of Experts were approved.

February 9, 2016—Arbitrary and sweeping disqualifications of moderate candidates for the upcoming elections in Iran by hardline bodies who control the approval process are stripping Iranians of their right to free and fair elections.

The Guardian Council, the clerical body charged with vetting all candidates in the Islamic Republic, has disqualified the vast majority of reformist and moderate candidates for Parliament and for the Assembly of Experts, the body that selects the country’s next supreme leader, in a process completely lacking in transparency or accountability.

“These disqualifications are creating a situation in which there is little competition among candidates or choice for the electorate,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. “So why bother with the charade of holding elections?”

“By rigging the elections to ensure that only hardliners will assume office, they are setting the stage for a government that has little domestic legitimacy,” Ghaemi added.

While fierce protests in Iran over the last few weeks against the disqualifications—by citizens, leading clerics, reformist leaders, and even Iran’s President, Hassan Rouhani—prompted the Council to reverse their decision on some of the disqualifications, roughly 40% of the applicants, the vast majority of whom are reformist or moderate, remain disqualified by the Council. All of these disqualified candidates had passed a prior vetting process undertaken by the Ministry of Interior.

The vetting process indicates that the hardliners’ base is narrowing to an unprecedented degree. The disqualified applicants are not dissidents, activists, secularists, and others that would present a more direct challenge to clerical rule. Rather, they are consummate insiders, long-time Islamic Republic leaders, and high-level clerical figures.

Their suspect loyalty to an increasingly hardline—many would say reactionary—clique of ultraconservative officials, led by supreme leader Ali Khamenei, and their willingness to entertain cooperative alignments with more moderate and pragmatic factions, rendered them unacceptable to the Council of Guardians.

In a January 21 speech to government officials, President Rouhani directly challenged the Council’s disqualifications in unusually strong terms, stating that Parliament was the “house of the people, not a particular faction,” and that elections would be pointless if there were “no competitors.” He asserted, “If there is one faction and the other is not there, they don’t need the February 26 elections—they go to the Parliament,” and added “No official without the vote of the people would be legitimate.”

In a letter published on February 9 and addressed to President Rouhani, 300 prominent academics and university professors in Iran expressed their deep concern for the “widespread disqualifications of candidates.”

“Under such circumstance, it is better not to hold a non-competitive and unfair election with limited citizen participation,” the academics warned in their letter.

“The Islamic Republic crows about its democratic credentials and regular elections, and uses them to legitimize its repressive political and social order,” Ghaemi said. “But handpicking candidates and engineering electoral outcomes has little to do with democracy and everything to do with legitimizing the silencing of its opponents.”

In addition, the disqualification process has been characterized by a stunning lack of transparency.

There is a two-step process for vetting candidates for Parliament. Applicants must first register with the Ministry of Interior. Of the initial 12,123 applicants that registered, the Ministry disqualified only 814 based on criteria such as pending legal cases or police investigations. Four separate agencies have to sign off on the applicant to pass the Ministry’s vetting process.

The Interior Ministry then sends all of the applications, both those it approved and those it disqualified, to the Council of Guardians for its vetting. Of those 12,123 applications, the Council approved only 4,816, or 40% in the first round. This is the lowest approval rate in the history of the Islamic Republic’s Parliamentary elections, Hossein Marashi, member of the Supreme Policy Council of Reformists told the Iranian Labor News Agency (ILNA) on January 17.

Thus 60% of the applicants were excluded in that first round, with disqualifications ruling out 99% of the reformist applicants.

Among the disqualified applicants, 3,637 of them were rejected because, according to the spokesperson for the Council of Guardians, Nejatollah Ebrahimian, who spoke to the Iranian Student News Agency (ISNA) on January 16, “it was impossible to confirm their qualifications based on the documents in their cases, considering the little time we had.”

In other words, no evidence was presented to substantiate grounds for their disqualifications. It is noteworthy that the reformist applications, all of which had passed the Ministry of Interior’s vetting, fell so disproportionately into the “no time” pile.

At a provincial meeting in the Central Province on January 18, Dorri Nafabadi, former Intelligence Minister and Arak Friday Imam said: “What does ‘not confirmed’ mean? We are not talking about one or two people here—qualifications of 40% of the applications have not been confirmed.”

Former President and Islamic Republic stalwart Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani also sharply criticized the process: “I agree that it is not possible to have 12,000 individuals registering for the parliamentary elections, and for all of them to compete in the elections,” he said. “But the way to deal with this is to have a law prior to the elections, saying those who want to become candidates must have a series of qualifications…We must not allow them to register when we have no time to review their cases, and fail to review their cases, and eventually tell them that their qualifications have not been confirmed. This is not the right way or methodology.”

The Guardian Council’s second round of vetting, underway now and prompted by the protests over the disqualifications, is faring only little better. As of this writing, the Council has re-affirmed the disqualification of some 55% of the applicants that had passed the Interior Ministry’s vetting.

The difference between the Interior Ministry’s vetting and that of the Guardian Council’s highlights the opaqueness of the electoral process in Iran. The Ministry’s vetting is overseen by multiple agencies and adheres to a clear process focused on pending judicial and police matters. The Council’s vetting is based on criteria such as allegiance to the Supreme Leader or allegiance to Islam—criteria that by their very nature are subjective, opaque and impossible to definitively discern or refute.

On February 7, a group of 60-70 Iran-Iraq War veterans who were disqualified gathered in front of the Council of Guardians’ Tehran offices. According to Khabar Online, the Secretary General of the Veterans and Constitution Defense Party, Alireza Matani, told Iran Newspaper they were disqualified due to insufficient commitment to Islam and to the Islamic Republic. He stated, “If they had disqualified us under any other reason, perhaps we would not have objected like this. [But] they said that the veterans do not have commitment to Islam…How could veterans, who for years fought in war fronts for Islam, and have become disabled for it, not have commitment to Islam now?”

As the extent of the disqualifications began to be clear, supreme leader Khamenei made his support for the vetting process clear: in a speech to election officials on January 20, he clarified an earlier statement he had made urging all citizens to vote by adding, “This does not mean that they could send individuals to the Parliament who do not believe in the Islamic Republic.”

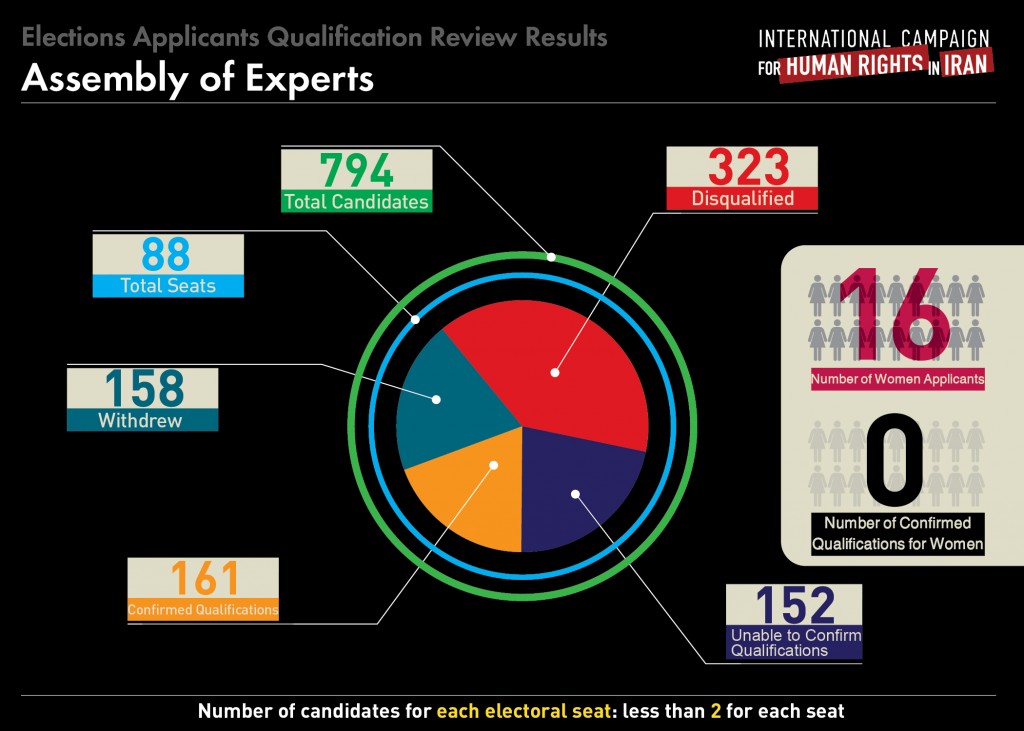

The Guardian Council demonstrated equal determination to block moderate applicants for the 88-seat Assembly of Experts. This body of Islamic clerics and scholars is important, as it is near certain that during its tenure it will select the next supreme leader to succeed the now-ailing, 76-year-old Ayatollah Khamenei.

The total number of applicants for the Assembly was 794; of these, only 161 were qualified, and 158 withdrew. The Council ruled out 152 applicants because they “couldn’t verify the qualifications”—again providing no substantiation for the rulings—and disqualified 323 applicants. Although 16 women registered as applicants, none were approved.

Strikingly, the Council disqualified a number of major ayatollahs and clerical leaders that are considered moderate or reformist-affiliated. These include Rasoul Montajabnia, Kazem Mousavi-Bojnourdi, Mohsen Gharavian, Seyed Hassan Khomeini (grandson of Ayatollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic), Hassan Namazi (an advisor to President Rouhani on clergy affairs), Majid Ansari (Deputy to President Rouhani for Parliamentary affairs), and Seyedali Mohammad Dastgheib, a current member of the Assembly of Experts.

Rage among established clerical figures in the Islamic Republic over these disqualifications was on public display, indicating the depth of the fissures within the political elite. Former president Rafsanjani had this to say: “When you do not confirm the qualifications of an individual who is most similar to his grandfather, Imam Khomeini, where did you receive your own qualifications? Who gave you permission to pass judgment? Who gave you permission to sit and judge? To take over all the authority for the parliament, the cabinet, and other places, too? Who allowed you to own the guns and the pulpits? Who allowed you to take over the Friday prayers podiums and the state radio and television?”

The extent of the electoral rigging was made clear by the fact that for many provinces in Iran, the number of applicants the Council approved for the Assembly of Experts equaled the number of seats allotted to that province (see chart). In other words, the Council of Guardians handpicked the candidates that would win those seats.

Nevertheless, the Iranian public seems determined to vote in the elections. Even President Rouhani, whose growing electoral popularity in Iran may translate into few vetted candidates among the centrists with which he is aligned, has exhorted people to vote. On February 7 he told a conference on women and development, “Although sometimes making a choice becomes very difficult, we must all, under any circumstances, appear before the ballot boxes on February 26. Electing officials is a huge duty and responsibility, and we know that if we are present, we will make gains, no matter how small. But by being absent, we will definitely suffer a loss, and it is clear that under such circumstances, we would choose the small gains.”

The prominent reformist Hossein Marashi added his support as well, telling ILNA on January 17, that reformists would carry on with the elections, vowing: “We will stay to fight because we don’t want extremists to grow.”