Union Leader: Less Pressure on Teachers Thanks to Rights Activists

Under Rouhani, “They have changed tactics from hard forms of pressure to milder ones.”

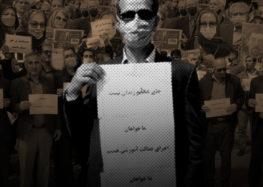

The leader of Iran’s largest teachers’ rights organization has said that due to pressure from civil rights activists, the government of President Hassan Rouhani has been less repressive towards teachers’ rights activists since the signing of the nuclear deal in July 2015.

“The reason why [imprisoned teachers] have been freed or are granted extended leave is because of the pressure put on the government by human rights groups,” said Esmail Abdi, secretary general of the Teachers Association of Iran, in an interview with the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.

“After the [Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action] JCPOA was signed, the government made a logical retreat in the face of pressure from the teachers’ community,” he said. “They had no choice but to let us go free and allow us to hold demonstrations and express our professional demands.”

The Teachers Association of Iran was formed in 1998 during the reformist administration of President Mohammad Khatami. Since then dozens of its members, as well as independent teachers, have been arrested and imprisoned for terms ranging from four to 15 years for peacefully defending teachers’ rights.

Although there are currently no members of the association in prison, some are awaiting trial and many of those who have been released have faced serious difficulties returning to their profession.

At least two teachers have also been executed. Hashem Shabaninejad and Hadi Rashedi were hanged in 2013 in the city of Ahvaz in Khuzestan Province based on confessions given under torture, according to one of their family members.

Rouhani Era

“There are now 16 labor groups that have permission to operate and hold general meetings. The government didn’t want this situation, but it has been forced to accept it,” said Abdi. “It is very clear that there’s a battle going on between [moderate] government officials on one side and hardline forces on the other. When we look closer, we see both sides belong to the ruling establishment, but the Rouhani government has acted a lot better, especially since accepting international demands under the JCPOA. These are all positive things.”

“During the [administration of former President Mahmoud] Ahmadinejad, there were no discussions [with leading teachers] and the operating permits of professional teachers’ groups were not renewed. But now we see change in the air in favor of teachers,” added Abdi.

Abdi noted that in accordance with Article 10 of the Parties and Associations Law, the Interior Ministry under Rouhani had issued permits for more than a dozen professional teachers groups, but had also demanded that their operations be limited to local provincial branches rather than to those of national entities.

“Ostensibly, they want professional organizations to expand and be active in every province. But … what they are really trying to do is to prevent us from having a national organization… I think this plan has been injected into the Interior Ministry by the security forces so that we would not be effective in all cities near and far,” said Abdi.

Independent unions are not allowed to officially operate in Iran, strikers often lose their jobs and risk arrest, and labor leaders who attempt to organize workers and bargain collectively are prosecuted under national security charges and sentenced to long prison sentences.

Abdi was arrested on June 27, 2015 by the Revolutionary Guards’ Intelligence Organization a week after being prevented from leaving Iran to attend an international teachers’ conference in Canada. He was subsequently sentenced to six years in prison by Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court and is free on bail awaiting a final ruling by the Appeals Court.

The former spokesperson for the Iranian Teachers Trade Association, Mahmoud Beheshti Langroudi, is also currently free on bail. In 2013 Judge Abolqasem Salavati of Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court sentenced Langroudi to five years in prison. He was released on bail in May 2016 after a 22-day hunger strike.

Banned from Work

In April 2016 Rassoul Bodaghi, a member of the Association and one of the most prominent labor activists in Iran, was conditionally released from prison after serving more than six years, but was banned from working again as a teacher. In July an informed source told the Campaign that Bodaghi has been harassed by the Intelligence Ministry since his release from prison.

“I am the only member of the Teachers Association who has been banned from work,” Bodaghi told the Campaign. “I haven’t asked to be reinstated. I will not beg officials of the Islamic Republic to let me go back to work. They unlawfully bullied me out of work and now they are sending over people to get me to come back and ask to be reinstated.”

“If they don’t ask me to come back to work, I will resume my activities and drag them to international tribunals for banning me and putting me behind bars,” he said.

Bodaghi was arrested on September 2, 2009 and sentenced to six years in prison for “assembly with the intent to disrupt national security” and “propaganda against the state.” He was also banned for five years from engaging in social activities.

He was conditionally released from prison on April 29, 2016, but has since been charged with “insulting the supreme leader” following an altercation with guards at a hospital who tried to prevent him from visiting a former cellmate.

Three other teachers—Abdolreza Ghanbari, Abdollah Momeni and Mohammad Davari—have also been banned from working in the educational system because of their political and civic activities.

At the time of his arrest on January 4, 2010, Ghanbari was a high school Persian literature teacher. Judge Abolqasem Salavati sentenced him to death for his alleged connection with the banned Mojahedin-e-Khalq (MEK) opposition group, but in February 2013 the Appeals Court reduced his sentence to 15 years in prison. In March 2016 Ghanbari received a pardon and was released. His wife told the Campaign that he was not mentally prepared to challenge his teaching ban and go back to work.

Momeni, a former prominent student activist, was arrested on June 20, 2009 while working as a high school social sciences teacher. He was released on March 13, 2014 after serving a five-year prison sentence. He was not banned from work by the court, but two years passed before his teaching license was reinstated.

Davari, a middle school teacher, was arrested on September 8, 2009 following a security raid on the headquarters of the moderate Etema Melli Party. Branch 28 of the Revolutionary Court sentenced him to five years in prison for “assembly and collusion against national security” and “propaganda against the state.” He was freed on September 8, 2014.

“Fortunately, I had not been banned from teaching, but I was banned for ‘unjustified absence from work’ during my imprisonment. I was able to get back my professional license in November 2015,” Davari told the Campaign in an interview.

Exile, Forced Retirement and Salary Cuts

“Most labor activists who faced security issues have been forcibly retired,” said Abdi. “Ali Akbar Baghani, Mahmoud Beheshti, Hashem Khastar and Mahmoud Bagheri have all been forced to retire. Mehdi Bohlouli and Mohammad Reza Niknejad were released on bail and could go back to work, but are awaiting to hear their fate from the Appeals Court.”

Baghani, a board member of the Iranian Teachers Association, was arrested at his home on April 29, 2010 by security forces. In January 2013 Branch 26 of the Revolutionary Court presided by Judge Yahya Pirabbasi sentenced him to a year in prison and two years’ exile for “propaganda against the state.” In March 2016 he was released from prison and in April he began his exile in the city of Zabol, in Iran’s impoverished Sistan and Baluchestan Province.

According to Abdi, the following teachers have been forced to move and work in other cities: Ali Sadeghi, Madar Ghadimi, Hamid Mojiri, Hamid Rahmati, Nabiollah Bastan, Peyman Modirian and Eskandar Lotfi. Abdi added that several teachers have been forced to retire before becoming legally eligible and others have received salary cuts because of their civic activities.

Fahimeh Esmailzadeh Badavi, a female elementary teacher from Khuzestan Province, has been in prison since 2005—longer than any other teacher, according to Ahmad Madadi, a former member of the Teachers Association of Iran. “Badavi was arrested in connection with issues concerning [Arab] minorities. Her husband was executed, but she’s still in prison,” Madadi told the Campaign.

“There’s a lot of pressure on teachers’ groups, especially in Khuzestan and Kurdistan Provinces,” added Madadi, who currently lives abroad. “For instance, Nasser Azizi has been exiled from Kurdistan to Semnan Province for five years. We’ve had about 700 cases of forced relocations, salary cuts and demotions.”

Madadi said that compared to Ahmadinejad era, teachers’ rights have improved under Rouhani, but that security pressures persist.

“What has happened is that they have changed tactics from hard forms of pressure to milder ones. Teachers get summoned and threatened by security agencies in order to make them reduce their activities,” he said.