Imprisoned Iranian-British Dual National Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe Pleas for Release in New Letter

Unjustly Jailed Mother Relays Torment of Separation from Her 5-Year-Old Daughter

Unjustly Jailed Mother Relays Torment of Separation from Her 5-Year-Old Daughter

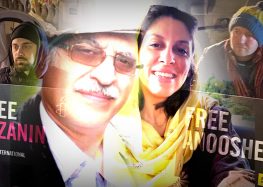

Iranian-British dual national Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe has made an impassioned plea for her release from prison in a new letter written from her cell in Iran’s Evin Prison. A copy of the letter was sent to the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) by Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s London-based husband, Richard Ratcliffe.

In the letter, Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who has been imprisoned in Iran for over three years and is the mother of a five-year-old daughter, speaks of her separation from her daughter Gabriella as the “deepest torture of them all.”

She writes:

“I sit in that cell today as the mother of a girl now 5, who was taken from me by my own country when she was only 22 months old. Those bleak first days of separation from my baby, when she had barely started to speak, passed with a bitterness beyond words. You have to be a mother and have experienced separation from your child to know the depth of what it means.”

Noting that Iran has put her “on sale,” referencing the fact that in July 2018, a judge reportedly told Zaghari-Ratcliffe that she was being held as a bargaining chip by the Iranian government to convince London to pay Tehran an old debt, she states: “I cannot imagine any politics that justifies separating a mother from her baby.”

In April 2016, Zaghari-Ratcliffe was arrested by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ intelligence organization and ultimately sentenced to five years in prison under unspecified and unsubstantiated espionage charges after an unfair trial completely lacking in due process. An employee of the Thomson Reuters Foundation charity, she has been eligible for release since November 2017 based on Article 58 of Iran’s Islamic Penal Code, which states courts can issue an order of conditional release after a convict has served one-third of their sentence.

The following is the complete letter from Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe:

To the Mothers of Iran:

Perhaps brushing your daughter’s hair seems such an ordinary part of your everyday routine. For me, these past 3½ years it has been a dream kept waiting.

Perhaps reading bedtime stories, going back for extra night time kisses pass unnoticed in their normality. Perhaps trips to the park or the library are something you struggle to squeeze in the time. For me, there are now years of envy, years of missing out.

Perhaps not being able to hold your baby is unimaginable. It is the image I struggle to escape even after all these years. The deepest torture of them all.

My heart pounds much more than usual every Sunday morning – when I get to see my Gabriella Gisou in the visiting room of Evin prison, full of excitement. When the door of the visiting room opens, and the prisoners are allowed in, it is my little girl who runs towards me first, calling out my name, rushing to my cuddle. Those brief minutes might be the shortest of cuddles, but without doubt the most beautiful and uplifting cuddles in the whole world. They are my world.

But then comes the stress – Sundays slip so soon through my hands, and fade away in the fog of the cell.

I sit in that cell today as the mother of a girl now 5, who was taken from me by my own country when she was only 22 months old. Those bleak first days of separation from my baby, when she had barely started to speak, passed with a bitterness beyond words. You have to be a mother and have experienced separation from your child to know the depth of what it means.

Last week another mother was released from prison, whose imprisonment was once connected to mine.

Negar is a mother who gave birth to her child in prison in a faraway land. Those of us with experience of prison have some sense of what she endured. There is a particular pain in having your baby taken from your chest, even while she is still breastfed. I remember that feeling, of waking in the middle of the night, all on my own, in a cold sweat at the sound of her cries ringing through my nightmares, the overwhelming worry in the small hours wondering what she was going through. That lingering echo of my sobbing, that hollow embrace of my arms now emptied of my baby, discarded in a dark grey solitary cell, stuck in an unknown place – perhaps that is also what she went through.

I have some experience of this pain. Like Negar I longed to embrace my baby, to kiss her and smell her milky scent, over these past months become years, hard and bleak. I understand well that such pain is experienced alone, beyond comparison and measurement.

Except for the obvious difference. The Judge has decided that due to her circumstances, and long separation from her baby, she had suffered enough. Her sentence was also her release.

Negar and I are fellow countrywomen. She had been convicted in a foreign country, whereas I was accused by the country of my birth. I was convicted in an unfair trial, even according to the UN, and was sentenced unfairly to 5 years. I have already been made to endure three quarters of this sentence, despite my begging and tears behind bars, despite my baby being denied her parents across such important years.

Now we are at the beginning of an even tougher road.

In the near future, my baby will leave me to go to her father and start school in the UK. It will be a daunting trip for her travelling, and for me left behind. And the authorities who hold me will watch on, unmoved at the injustice of separation. That first day of school not for me.

My country constantly talks about the separation of Yemeni, Syrian and Palestinian mothers from their children. Yet it remains blind to the pain of separation of a mother and baby in her homeland. It even adds to that pain.

Last week my country put me on sale – in return for a huge amount of money, using me for its own political benefits. Was it a surprise? My hope for freedom from my own country died in my heart years back.

My country did not defend me or my baby’s rights, but marketed me for its negotiations. Those who violate human rights – in the eyes of Iran – turned a blind eye on Negar’s fault, and let her go to her baby.

By contrast the Iranian authorities accuse me of something I have never done, convict me and hold me – and have no mercy still. And in the stand-off, it is only me, my baby and my husband who pay the price. Not the governments who play with our lives.

It is such a bitter feeling to know you are stuck unjustly in prison in your own country, with no road to freedom ahead. I am a desolate mother ready to burn like a desert dune when her baby leaves, unable to see any light in this tunnel without end.

I have no hope or motivation after my baby goes. There is no measure to my pain.

As Negar returns to Iran, her baby is exactly the same age as when my Gisou was taken from me. It has brought back that memory. Even now I cannot imagine any politics that justifies separating a mother from her baby.

Even now I remain a pawn in the hands of politicians – abroad and in Iran – to reach their goals in their games of chess. Some have used every opportunity these past years to use a mother and baby as political leverage. They did not leave anything behind.

Perhaps if humanity, morality and religion, as practised in a true Islamic country, existed in the hearts of politicians and decision makers, our world would be a better place, and the pain of Iranian mothers a lot less.

In that world, perhaps I would have been able to see my baby on her first day of school. In that world, freedom would sing a song long and soft as brushing my little Gisou’s hair. And one day that will be our everyday.

Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe

Mother of Gabriella Gisou Ratcliffe

Evin Prison, Tehran, Oct 2019