Iran’s Workers: Battered by Brutal Repression and Lethal Work Conditions

19 Labor Activists Still Imprisoned, One Woman at Risk of Execution

Over 2000 Workers Dead in Last 12 Months Due to Unsafe Working Conditions

April 30, 2025 – On this International Labor Day, the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) draws urgent attention to the plight of Iranian workers—the true backbone of the nation’s economy—who are being relentlessly persecuted simply for demanding what should be universal: livable wages, safe working conditions, and basic labor protections.

Peaceful labor leaders are met not with dialogue, but with repression. They face arbitrary arrest, sham trials, and years behind bars. As of today, 19 labor activists are imprisoned in Iran, with one courageous female advocate now facing the possibility of execution. Their crime? Standing up for dignity and justice in the workplace.

According to the latest research:

- At least 19 labor activists remain imprisoned, including Sharifeh Mohammadi, who is at grave risk of being hanged following her death sentence. (See list below.)

- More than 2081 workers have died due to grossly unsafe working conditions from May 1, 2024, to April 27, 2025.

“Iran’s workers are oppressed and mercilessly exploited by the state as cheap and disposable labor, while their leaders are arrested, flogged, and imprisoned by a government that shows no regard for their rights, safety, or dignity,” said Bahar Ghandehari, CHRI’s director of communications.

“While labor leaders languish behind bars in Iran, hundreds of workers lose their lives each year due to grossly inadequate safety standards, workers in industries across Iran struggle to survive with unpaid wages, and millions of children labor in the workforce, due the Iranian government’s deliberate failure to enforce labor laws,” Ghandehari said.

“Desperate for employment, workers in Iran are deeply vulnerable, especially members of impoverished and marginalized minority communities, women who face systemic abuse and discrimination, and children who are forced into the workforce,” Ghandehari added.

CHRI urges the international community to speak out for the rights of Iran’s oppressed workers, and publicly support those who continue to protest the severe abuses they face by amplifying their demands and defending their right to protest. Indeed, in just the last four months alone, there were at least 44 labor protests and strikes across 26 cities in Iran. (See list below.)

The UN, the International Labor Organization (ILO), international trade associations, and governments worldwide should call upon the Iranian authorities to:

- Immediately and unconditionally release all imprisoned labor leaders.

- Recognize the right of independent unions to form, collectively bargain, and strike, and for workers to peacefully protest.

The cases documented in this report reveal a continuing pattern of:

- Criminalization of Labor Activism: Authorities treat independent labor activities as national security threats and do not recognize independent unions. State-controlled “Workers Houses” operate in lieu of independent unions, providing workers with little, if any, agency. Strikers risk arrest, and independent labor leaders receive long prison sentences.

- Denial of Due Process: Many arrests occur without warrants, and detainees are often held incommunicado and denied legal representation.

- Retaliation Against Protest: Activists who expose human rights violations inside prisons face intensified punishment, including enforced disappearances.

- Use of Exile and Forced Displacement: Authorities impose internal exile sentences on activists to isolate them from their communities.

- Health Endangerment: Imprisoned labor leaders with serious illnesses are routinely denied access to proper medical care as a form of additional punishment.

Criminalization of Labor Rights Advocacy Leaves Workplace Abuses Untouched

The persecution of the country’s labor leaders, the inability of workers to organize effectively and bargain collectively, and the inability of civil society, NGOs, rights activists, and journalists to operate freely in Iran, undermine Iranian society’s ability to address the multitude of severe workplace abuses that Iranians face. These include:

- High work fatalities: Workplace fatalities in Iran have steadily increased from already extremely high levels, due to egregiously poor safety standards. (See discussion below)

- Unpaid work: Iranian workers routinely struggle with non-payment of wages, sometimes for months, and encounter significant difficulties in collecting back pay.

- Denial of benefits: Iran’s workers are often denied benefits and critical social protections required under Iranian law, such as pensions and health insurance.

- Unlivable wages: Iranian workers struggle with wages that are often below the poverty line, even as they face annual inflation rates exceeding 40%. Indeed, what many workers in Iran earn is not just below the poverty line, it is barely sufficient to stay alive. The World Bank estimates that some 28% of the population lives below the international poverty line, with 40 percent of Iranians “vulnerable” to falling into poverty.

- Temporary contracts: The ubiquitous use of temporary contracts in Iran (some 90% of workers are employed under them) means that workers have no security and are thus forced to accept even lower pay and none of the benefits required under Iranian law.

- Widespread use of child labor: Iranian laws prohibiting child labor for children under 15 are not enforced; millions of children are forced into employment, especially in small and family-based workplaces that are exempt from regulations. Children are most frequently used in the textile industry, waste disposal, mining, agriculture, construction, domestic work, and street vending.

- Discrimination: There is systemic workplace discrimination, in both hiring and pay, against women (who have twice the unemployment level and can be prevented from working or fired at the husband’s behest), members of ethnic and religious minority communities (applicants are often required to state their religion, and Baha’is are routinely refused work), and persons with disabilities (who face widespread inaccessibility issues).

CHRI urges the UN, the International Labor Organization (ILO), international trade associations, and governments worldwide to call upon the Iranian authorities to:

- Implement international occupational health and safety (OHS) standards, with increased training programs and rigorous enforcement and monitoring.

- Implement strict enforcement and monitoring of prohibitions against child labor.

- Demand that workers promptly receive all wages due as per international law, as well as guaranteed insurance, pensions, and other protections.

- End discriminatory labor practices against women, members of religious and ethnic minority communities, and others.

Daily Realities for Iran’s Workers: Unlawful Arrests and Enforced Disappearances

Discussions CHRI has recently held with workers in Iran and with members of their families illustrate the abuses and hardships Iranians face, especially if they engage in any kind of peaceful labor activism aimed at addressing severe and rampant workplace violations.

On January 8, 2025, Taregh Kaabi, a 29-year-old father of two and worker at the Haft Tappeh Sugarcane Company, was violently removed from a workers’ shuttle bus on his way to work by Ministry of Intelligence agents. Kaabi, a resident of Shush and brother to former political prisoner Maher Kaabi and current prisoner Ahmad Kaabi, was arrested for allegedly sharing content online about labor conditions. For nearly a month, his whereabouts were unknown.

A source, unnamed for security reasons, familiar with Tareq Kaabi’s case told CHRI:

“Unfortunately, access to Mr. Kaabi’s case is extremely difficult, and for nearly a month after his arrest, there was no information even about his whereabouts. The only thing we know about Tareq now is that he is being held in Dezful Prison.

“Tareq’s brother, Maher Kaabi, was released from Ardabil Prison a few years ago after serving 10 years without a single day of furlough. In recent years, several other members of their family have also faced lengthy prison sentences due to political activities. It appears that one of the reasons for Tareq Kaabi’s arrest is the political background of his family.”

Kurdish Labor Activist: Denied Medical Care for Severe Illnesses in Prison

Isa Ebrahimzadeh is a Kurdish farmer and labor rights activist who has been imprisoned in Naqadeh Central Prison. He and members of his family have been repeatedly targeted for their peaceful labor activism, including their work for the Coordinating Committee for Helping to Form Workers’ Organizations.

Ebrahimzadeh, who developed heart and intestinal illnesses in prison, was previously denied leave even as his young, ailing son died in his absence. He was arrested after participating in the Woman, Life, Freedom protests, spent 50 days in solitary confinement at the Ministry of Intelligence detention center in Urmia, and was denied access to a lawyer. In a trial riddled with due process violations, he was sentenced to five years in prison without being granted the right to an independent lawyer by the Revolutionary Court of Oshnavieh, presided by Judge Rezaei.

The charges against him included “membership in opposition groups,” “participation in gatherings,” “propaganda against the regime,” and “assembly and collusion.”

Ebrahimzadeh was finally granted a 14-day medical furlough for treatment on April 20, 2025, but only after his condition had deteriorated drastically due to prison officials’ refusal to allow him access to hospital care and proper medical treatment—and under the condition that he would have to obtain and pay for the treatment himself during his medical leave.

Behnam Ebrahimzadeh, Isa’s brother, told CHRI:

“This 14-day furlough has been granted to Isa under highly unusual conditions —these 14 days will not be counted toward Isa’s prison term. This is happening even though Isa has developed multiple illnesses during his imprisonment, and prison officials are directly responsible for his deteriorating condition [due to their denial of medical care for him whilst in prison]. However, because the costs of Isa’s treatment are very high and the authorities want to avoid any responsibility, they granted him this medical leave under these conditions.

“Isa’s physical condition, especially his heart problem, has worsened significantly compared to two years ago. During this time, Isa’s young son, who was suffering from an illness, passed away. Our family protested in front of the Intelligence Ministry building, but Isa was still denied furlough, leading him to attempt suicide in protest. Although he survived, Isa’s current condition is extremely poor — physically, mentally, and financially — especially since he was the family’s sole breadwinner.

“Granting this 14-day furlough with these conditions means Isa must obtain and bear the full cost of his treatment during his leave; the prison refuses to accept any responsibility, even though it was the prison conditions and the refusal to grant him medical treatment that caused his health to deteriorate.

“One of Isa’s illnesses, an intestinal infection, is contagious, and prison officials were aware of it. When the illness worsened recently, Isa was sent to Naqadeh Hospital for two days, where it was confirmed that his condition was contagious. Nevertheless, he was returned to prison. A day later, they handed him the furlough papers. When Isa realized this was technically a ‘pause’ in his sentence rather than a regular medical furlough, he protested, but prison officials forced him to accept it.

“We have always been a working-class and politically engaged family. Our father was once a member of the Coordinating Committee to Help Form Workers’ Organizations, and because of that, my brother and I also got involved in labor rights activities. All our activities were legal — we did nothing illegal.

“Although Isa was a simple farmer, he deeply cared about social justice. He was actively involved in the Woman, Life, Freedom protests. He was sentenced to prison after an entirely unfair trial. Isa spent a month and a half in solitary confinement, and the legal process was completely opaque — he wasn’t even allowed access to a lawyer.”

Labor Activist: Years in Prison for “Insulting” the Supreme Leader

On February 10, 2025, Mohammad Davari, a labor activist serving a sentence in Adilabad Prison in Shiraz, was taken to an unknown location for 17 days—and then returned to prison.

An informed source told CHRI that this abduction, which was the second time he was abducted incommunicado from prison, was in response to an open letter Davari wrote to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei a month earlier in January 2025, describing the torture, threats of sexual violence, and fabricated charges he was subjected to during his earlier abduction in December 2024. His sentence—three years for “insulting the Supreme Leader” and 1.5 years for “propaganda against the regime”— included a two-year travel ban and exile to Bardsir, Kerman.

In his letter to Khamenei, Davari wrote:

“I have heard your recent statements emphasizing action against those who disturb society’s ‘psychological security.’ Yet, not even a month after my father’s death, I was abducted from prison [in December 2024] under such brutal conditions, leaving my mourning family — who were preparing for his fortieth-day memorial — in a state of terror and despair. … I was beaten so severely that my ribs and chest were bruised, my nose bled, my feet were wounded, my glasses were broken, I was humiliated and sexually threatened with a broken bottle to silence me. For what crime? For what purpose?”

The Price of Criminalized Labor Rights Activism: “Every worksite resembles a battlefield”

Without the ability of labor rights activists to address workplace violations, these abuses continue—and worsen. One especially lethal aspect of this deterioration is workplace fatalities in Iran due to egregiously unsafe working conditions. Iran has an extraordinarily high workplace fatality rate compared to other countries, including countries who are at similar levels of economic development.

From May 1, 2024, to April 27, 2025, at least 2,081 workers in Iran lost their lives, and at least 16,273 workers were injured in workplace incidents, according to HRANA. Among the victims was Salman Vodkar, a 16-year-old child laborer from the village of Irafshan in Sistan and Baluchistan province. Due to a lack of transparency and large numbers of unreported deaths of undocumented workers, the true number is far higher.

Official Iranian statistics show a steady increase in workplace fatalities over the past few years. In the first half of 2024 alone, 1,077 workers died—approximately 200 per month. In 2023, official figures recorded 2,115 workplace fatalities—up from 1,900 in 2022, 1,817 in 2021, and 1,755 in 2020.

In a March 2025 workshop on workplace safety, Hossein Moshiri Tabrizi, Director-General of International Affairs at Iran’s Social Security Organization, said that workplace accidents claim two to three lives every day, adding that “every worksite resembles a battlefield.”

Workplace accidents are the second leading cause of death in Iran, with construction workers (60% of workplace deaths) and mine workers especially vulnerable due to the near-total absence of safety protocols and weak regulatory oversight. The most recent mining tragedy occurred on April 7, 2025, when seven miners died from gas poisoning at the Javaher Coal Mine in Mihanduiyeh, Damghan. On September 21, 2024, an explosion from a methane gas leak at a coal mine in Tabas, South Khorasan Province, killed at least 51 workers and injured 20 others.

Most recently, on April 26, 2025, a massive explosion tore through Iran’s largest commercial port at Shaheed Rajaei Port in southern Iran’s Bandar Abbas city, killing at least 40 people and wounding over 1,200 others. The numbers of fatalities are expected to rise. Although the cause of the explosions is not yet clear, initial reports suggest mishandling of chemicals by authorities caused massive fires, and Iranian officials have pointed to improperly observed safety procedures. Arsalan Heidari, a member of the executive board of the Hormozgan Workers’ House, said:

“Fifty-five percent of the country’s imports and exports pass through Shahid Rajaee Port in Bandar Abbas, where approximately 11,000 workers are engaged in loading and unloading cargo. Unfortunately, general and specialized safety measures are not properly observed at the port.”

CHRI echoes the call by the Coordinating Council of Iranian Teachers’ Trade Associations on April 27, 2025, for transparency and independent investigations.

“The Coordinating Council of Iranian Teachers’ Trade Associations …emphasizes the bitter truth that the deprivation and neglect of workers’ livelihoods and safety are the result of years of injustice and mismanagement. …we call for full transparency regarding the causes of this tragedy, the firm prosecution of those responsible for negligence, and compensation for the victims’ families. We hope that the unjustly shed blood of these oppressed workers will serve as a beacon to awaken dormant consciences and drive the reform of the broken structures.”

The statistics cited here only account for deaths caused by workplace accidents. They do not include the huge numbers of workers who are severely injured, or the large numbers of workers who die from illnesses (or are made seriously and/or permanently ill) due to improper and unsafe exposure to dangerous substances.

There are many reasons for Iran’s extremely high workplace fatality rate, including:

- Substandard OHS conditions in Iran are largely due to grossly inadequate monitoring and enforcement, demonstrated in insufficient inspections, supervision and penalties for violations. Official Iranian statistics indicate 800 auditors serve 12 million registered workers—which amounts to one auditor per 15,000 workers. Iranian studies have noted a lack of management commitment to safety protocols, severely inadequate training in safety procedures, and the absence of even the most basic protective equipment. The lack of NGOs and civil society organisations able to advocate for more rigorous OHS standards exacerbates the problem.

- Corruption: Widespread corruption and bribery also undermine the enforcement of OHS standards. Systemic corruption in Iran allows employers to avoid accountability and continue to operate hazardous workplaces that claim lives or leave workers maimed, sick, and in constant danger.

- A high proportion of Iranians work without insurance, in violation of Iranian law and international standards that workers be covered. Iranian government reports estimate a third of Iranian employees are not insured at all. Of the two thirds, many are self-insured and thus significantly underinsured. Lack of insurance means workers and employers don’t report workplace accidents or illnesses, and OHS violations are left unchecked.

- Temporary contracts: The lack of insurance also arises largely from the roughly 90% of Iranian workers who are employed under temporary contracts. While insurance is required under these contracts, this is not enforced and often not provided. The lack of job security under them makes workers unlikely to demand insurance or make OHS complaints.

- Exempt workplaces: Under Article 191 of Iran’s Labor Code, workplaces with fewer than 10 employees are exempt from major portions of Iran’s labor regulations. As a result, many companies artificially break their workplaces up into smaller units to avoid labor regulations and safety requirements. Family-run operations and certain agricultural sectors are also exempt from key labor regulations. These legal loopholes leave a major portion of the country’s workplaces unregulated and unprotected, and millions vulnerable to exploitation, as such enterprises are estimated to represent as many as 50% of Iranian workplaces. Children and women in particular are likely work in these unregulated and unprotected settings.

- Opaque subcontracting: Companies and even major municipalities in Iran routinely subcontract work to private sector companies without any contracts; as such there are no records of this work—and no accountability for even the most severe OHS violations. Such subcontracting is often carried out through companies that are labeled “private,” but in fact operate under state or quasi-state control. This has become so commonplace in Iran that the public refers to these entities using the term: KhosooLati—a combination of Khosoo (from “khosousi”/private) and Lati (from “dolati”/state-run), reflecting their hybrid and opaque nature.

- Large numbers of refugees and migrant workers in Iran—many of whom are undocumented— contribute to the problem as they provide employers with a large pool of desperate labor unable and unwilling to register OHS complaints, especially in the construction industry, where many work.

- The informal economy: One out of three Iranian workers is estimated to be working in the unregistered and unregulated informal economy, for which there is no accountability for health and safety violations, and whose deaths, injuries, and illnesses go unreported.

The Ongoing Persecution of Labor Activists

The Islamic Republic’s persecution of labor leaders and its criminalization of independent labor organization and activism are in severe violation of its obligations under the International Labor Organization’s (ILO) Fundamental Principles, to which Iran is a signatory, as well as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), all of which require respect for the right to peacefully protest, to strike, and to independently organize and bargain collectively.

The following is a list of recent publicly reported cases of such persecution just during the first four months of 2025; there were likely many more such cases.

- On January 6, 2025, Sosan Razani, a well-known women’s and labor rights activist from Sanandaj, was interrogated and accused of “propaganda against the state” and “disturbing public opinion.” She was released on bail and tried with six other activists in April. Razani has faced repeated arrests over the years, and was previously sentenced to suspended prison terms and lashes for participating in an International Workers’ Day event.

- On January 22, 2025, judicial authorities rejected labor activist Fouad Fathi’s request for conditional release, despite his serious lung infection requiring specialized medical care and the denial of medical care in prison. Arrested in November 2024, Fathi was sentenced by Branch 26 of the Tehran Revolutionary Court to four years in prison, two years of exile from Tehran, and bans on group membership and social media activity.

- On January 18, 2025, five labor activists from the city of Sanandaj—Majid Hamidi, Seyed Ghaleb Hosseini, Abdollah Kheyrabadi, Namegh Babakhani, and Eghbal Shabani—were summoned and interrogated by the local Intelligence Office.

- On January 24, 2025, labor rights advocates Amjad Garma Khizi and Naeem Dousti—members of the anti-death penalty campaign—were arrested without a warrant on the streets of Kurdistan while working at a pastry shop. Dousti was released on bail on February 20, and Garma Khizi was freed on March 7.

- On January 25, labor activist Jalil Mohammadi was arrested at his home in Sanandaj without a court order. According to the Kurdistan Human Rights Network, his arrest was linked to his participation in a bazaar strike protesting the death sentences of Varisheh Moradi and Pakhshan Azizi. He was released on bail on March 9, 2025.

- On February 6, 2025, former political prisoner and labor activist Kamran Sakhtemangar was arrested in Sanandaj and transferred to an unknown location. Though acquitted of the charge of “assembly and collusion” by Branch 1 of the Sanandaj Revolutionary Court, he was convicted of “propaganda against the regime through social media activity and interviews with television networks.” He was sentenced to three months in prison and a financial penalty. He was released on bail on March 11, 2025.

- On February 9, 2025, imprisoned labor activist Morteza Saeedi, who was granted a two-week furlough following his father’s death, was forced to return to Evin Prison. On March 19, prison officials ordered his transfer to a different ward without explanation. Saeedi, citing the prison regulation requiring the separation of prisoners based on the nature of their offenses, objected to the transfer. In response, prison authorities transferred him to Evin’s quarantine ward, prompting him to launch a wet hunger strike. He had been sentenced to two years in prison in July 2024 for allegedly forming a workers’ union to disrupt national security. He was arrested on November 6, 2024, after appearing at Branch 3 of the Sentence Enforcement Office in Shahre Qods to begin serving his prison term. He was sentenced to two years in prison on the charge of “forming a group under the name of a labor union with the intent to disrupt national security” by Branch Two of the Shahriar Revolutionary Court.

- On February 13, 2025, Iranian authorities once again sentenced female labor activist Sharifeh Mohammadi to death, despite the Supreme Court previously overturning her initial death sentence. Mohammadi was arrested in December 2023 on bogus charges solely in retaliation for her peaceful activism and handed a death sentence following a sham trial marked by torture, forced “confessions,” and grave due process violations.

- On March 8, 2025, labor activist Farhad Sheikhi’s two-year exile sentence was enforced. In July 2024, Sheikhi was sentenced by Branch 1 of the Karaj Revolutionary Court, presided over by Judge Seyed Mousa Asif al-Hosseini, to one year in prison, two years of exile to Divandareh in Kurdistan Province, a two-year travel ban, and a two-year ban on residing in Alborz and Tehran provinces following the completion of his exile. He was convicted on the charge of “propaganda against the Islamic Republic.”

- On April 7, 2025, eight labor and civil rights activists from the city of Sanandaj, including Seyed Khaled Hosseini, Jamal Asadi, Iqbal Shabani, Fardin Mirki, Shith Amani, Farshid Abdollahi, Arman Salimi, and Susan Razani, were tried in Branch 1 of the Sanandaj Revolutionary Court on charges such as “anti-regime propaganda” and “disrupting public order and peace. Participation in political song performances and attending the funeral of justice-seeking mother Dayeh Farasat were cited as evidence. All had been previously interrogated in January and released on bail.

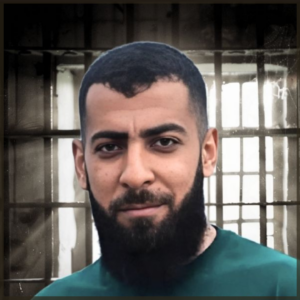

Labor Activists Still in Prison in Iran (Photos followed by names underneath):

1. Sharifeh Mohammadi, Lakan Prison, sentenced to death

2. Mohammad Davari, Adelabad Prison, sentenced to three years in prison; banned from leaving the country with passport revoked; banned from social media activity; two years of forced residency in Bardsir, Kerman

3. Nahid Khodajou, Women’s Ward, Evin Prison, Sentenced to six years and 74 lashes

4. Peyman Farhangian, Azbaram Prison, sentenced to six years; two years of forced residency in Zabol; two-year travel ban

5. Esmail Gerami, Evin Prison, sentenced to one year in prison and fined 20 million tomans

6. Nasrin Javadí, Evin Prison, sentenced to seven years and 74 lashes

7. Davoud Razavi, Member of the board of the Syndicate of Workers of the Tehran and Suburbs Bus Company, Evin Prison, Sentenced to five years in prison; two-year ban on social media and political group activities

8. Fouad Fathi, Evin Prison, sentenced to four years in prison; banned from leaving the country, joining political/social groups, and residing in Tehran or surrounding areas for two years (Kurdish)

9. Maziar Seyednejad, Evin Prison, sentenced to two years in prison; two-year bans on travel, political affiliation, and social media activity

10. Morteza Seydi, Evin Prison, sentenced to two years in prison (Kurdish)

11. Hajar Saeedi, Sanandaj Correction and Rehabilitation Center, sentenced to one year in prison (Kurdish)

12. Mehran Raouf, Evin Prison, sentenced to seven and a half years in prison (British-Iranian dual national)

13. Reyhaneh Ansarinejad, Evin Prison, sentenced to four years in prison; two-year ban on political and media activities and international travel

14. Sepideh Qoliyan, Evin Prison, Re-arrested just hours after completing a 4-year and 7-month sentence; sentenced again to two years in prison

15. Anisha Asadollahi, Evin Prison, sentenced to five years in prison

16. Narges Mansouri, Evin Prison, sentenced to nine years in prison

17. Ebrahim Madadi, Evin Prison, sentenced to one year in prison

18. Isa Ebrahimzadeh, Naghadeh Central Prison, sentenced to five years in prison (Kurdish)

19. Tareq Kaabi, Dezful Prison, No information available about sentence (Arab)

In just the first four months of 2025, at least 44 labor protests and strikes took place across Iran.

Despite the risks of prosecution and termination of employment, Iranian workers continue to protest the severe rights violations they continuously face. The following is a list of publicly reported protests and strikes that took place in Iran just during the first four months of 2025; there were likely many more such protests and strikes.

- January 1, 2025 – Abadan Petrochemical workers held a protest for the second consecutive day in front of the city governor’s office.

- January 3, 2025 – Families of Tabas coal miners protested against poor living conditions. They said miners have only worked two weeks since the Tabas mine disaster and received no pay during unemployment periods.

- January 9, 2025 – Strike and protest by Iran Ofogh Company workers in Khorramshahr. Workers laid out empty tablecloths during the protest.

- January 10, 2025 – Protest by Chouka Factory workers against unpaid wages. Retired workers of Chouka had also protested earlier in front of the Social Security Office in Rezvanshahr.

- January 12, 2025 – Protest by contract operational workers (Arkan Aval) in South Oilfields demanding employment status changes, job classification, bonuses, contractor removal, and tax exemption from oil cards.

- January 13, 2025 – Protest by laid-off workers of Arghavan-Gostar Petrochemical Company in front of Persian Gulf Holding in Tehran.

- January 13, 2025 – Protest by poplar growers, workers, and producers in front of Gilan Province Governorate.

- January 18, 2025 – Protest by Chouka Factory employees in Rezvanshahr, Gilan, over unpaid wages.

- January 19, 2025 – Protest by retired workers in front of the Khuzestan Social Security Organization in Ahvaz, at Labor Square.

- January 26, 2025 – Protest by third-party oil and gas workers in front of the Presidential Office.

- January 27, 2025 – Protest by contract workers of Fajr Jam Gas Refinery in Bushehr.

- January 29, 2025 – Protest by firefighters in front of Mashhad Governor’s Office regarding wage calculations.

- January 30, 2025 – Protest by third-party and contract workers of Iranian Offshore Oil Company, Lavan.

- February 1, 2025 – Protest by health workers and rural health workers in front of the Qorashi Building, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

- February 4, 2025 – Protest by workers of the Karun Irrigation and Drainage Networks Operations Company in Ahvaz.

- February 7, 2025 – Protest by third-party workers in the Lavan Oilfield region.

- February 12, 2025 – Protest by Khazar Steel Smelting Factory workers in Gilan over unpaid demands and job insecurity.

- February 15, 2025 – Strike by Kerman Telecommunication contract workers over unmet demands.

- February 15, 2025 – Babol Textile Factory workers in Borujerd stopped production for three days to protest unpaid wages.

- February 18, 2025 – Strike and protest by Bandar Imam Petrochemical Holding employees in Mahshahr over living conditions.

- February 18, 2025 – Protest by Fajr Jam Gas Refinery contract workers.

- February 18, 2025 – Strike and protest by workers of Petro Niro Saba Company (project executor at Karun Petrochemical) over three months of unpaid wages.

- February 18, 2025 – Protest by Borujerd Textile Factory workers.

- February 22, 2025 – Protest by Southern Oil workers hired in 2013 over poor living conditions and wage discrepancies.

- February 22, 2025 – Protest by rural health workers (hospital staff) in Minab, Hormozgan Province.

- February 24, 2025 – Protest by Iranian Offshore Oil Company permanent employees in Lavan Operational Zone.

- March 1, 2025 – Protest by third-party workers in Nar and Kangan Operational Zones in Bushehr.

- March 4, 2025 – Protest by native personnel of Jahaan Pars Company in front of Sarcheshmeh Copper Complex HR office in Rafsanjan.

- March 9, 2025 – Protest by third-party company employees in South Oilfields.

- March 13, 2025 – Farmers from eastern Isfahan villages, including Varzaneh and Ajieh, protested again with their tractors.

- March 17, 2025 – Protest by Iranian Offshore Oil Company permanent employees in Lavan Operational Zone.

- March 24, 2025 – Protest by Iranian Offshore Oil Company permanent employees in Lavan Operational Zone.

- March 26, 2025 – Seasonal sugarcane workers at Haft-Tappeh Sugarcane Company were attacked by security forces after protesting job losses caused by mechanization. Several workers and security guards were injured, and some workers were arrested.

- April 5, 2025 – Protest by Haft-Tappeh workers over water shortages affecting sugarcane fields.

- April 12, 2025 – Protest by women school-bus drivers in front of the House of Industry and Mine in Isfahan.

- April 12, 2025 – Protest by workers of Iran Poplin Company in Rasht over unpaid March 2025 wages.

- April 13, 2025 – Large protest by Gachsaran Oil workers (third-party and contract workers).

- April 19, 2025 – Protest by Fars Regional Electricity workers in front of the Ministry of Energy in Shiraz.

- April 20, 2025 – Strike and protest by South Pars Phase 12 Refinery contract workers.

- April 20, 2025 – Protest by Tehran Metro Operation Company workers in front of Tehran Municipality.

- April 21, 2025 – Protest by Gachsaran Oil and Gas Company contract workers and South Pars Phase 12 third-party workers.

- April 22, 2025 – Protest by Iranian Offshore Oil Company workers in Lavan Operational Zone, Bushehr.

- April 22, 2025 – Protest by Welfare Organization staff in Tabriz over low wages and poor living conditions.

- April 23, 2025 – Strike and protest by Lorestan Gas Company’s contract drivers.

This report was made possible by donations from readers like you. Help us continue our mission by making a tax-deductible donation.