Rouhani’s Post-Deal Test Starts in Paris

This op-ed was originally published in French.

By Hadi Ghaemi

This week, President Hassan Rouhani will visit Europe, including France, his first trip since the implementation of Iran’s nuclear deal. The two governments will focus on boosting economic ties, and Rouhani will seek to end years of Iran’s isolation. But what is at stake for the Iranian people, and what should President Hollande be aware of when meeting with Rouhani?

Rouhani left Iran just a few weeks before the parliamentary elections. Rouhani hopes that on the heels of the nuclear deal and the lifting of sanctions, his supporters would be able to participate in the elections, and then once elected into parliament, provide support for his policies. But Iran’s powerful hardliner Guardian Council, supported by Iran’s Supreme Leader, has brutally disqualified most of the reformist and moderate candidates, leaving no hope for the president’s supporters to even participate, let alone gain a majority. If Rouhani fails to reverse this unequivocal ban, his success in achieving the nuclear deal will not translate into domestic reforms.

Rouhani should ensure that the elections are free and fair. With just a few weeks left until the next parliamentary election, Rouhani faces a critical test: will he leverage the good will generated by the nuclear deal to finally deliver on his original campaign promise to bring about much needed human rights reforms?

The international community, and France in particular, can help. As a party to the agreement, a EU leader, and an important potential trade partner with Iran, France should leverage its standing and demand Rouhani prioritize human rights.

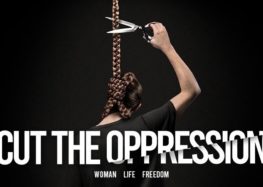

Human rights violations in Iran are not going to end on their own. In 2015, Iran achieved a new low – the highest number of executions in a single year in 20 years – more than 960. Women are facing a wave of new potential legislation that would impact their access to work, education, and health. Most importantly, there is effectively no room to express dissent to these and other troubling policies. Take the case of 28-year-old Atena Faraghdani. Locked up in Evin Prison, she awaits an Appeals Court decision on her 12-year prison sentence for drawings she posted on Facebook mocking Iranian lawmakers for passing a law outlawing surgical contraception.

The Revolutionary Guards has been aggressively arresting activists and critics. In November, the powerful security and military organization detained high profile journalist Issa Saharkhiz and three other journalists. Many commentators saw this move as an attempt by hardliners to take measures that would ensure the upcoming parliamentary election does not become an opportunity for critical voices to assert themselves. Hardliners fear candidates will get elected who would back Rouhani and push for human rights reforms.

Indeed, just last week, Iran’s Guardian Council disqualified an astonishing 99% of the reformist candidates among the more than 12,000 total candidates applying to run in this election. Rouahni has called these disqualifications illegal, but he must do more. Hollande should encourage Rouhani to use all the means at his disposal to make these elections as open and transparent as possible.

Transparency and cooperation should be key among France’s demands. Over the past decade while the rest of the world was busy placing economic sanctions on Iran, Iranian authorities were in effect self-imposing civil and political sanctions on the country by increasingly cutting off relations with international human rights, development, and humanitarian bodies. In this regard, Hollande should remind Rouahni that Iran has a responsibility to work with United Nations human rights mechanisms, most importantly among them the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Iran, who has never been permitted to visit the country – and therefore, not able to fully perform his job. This cooperation should extend to international human rights organizations, such as Human Rights Watch, Amnesty International, and the International Federation for Human Rights (FIDH), none of which are currently allowed to visit the country.

There are partners for reform within the Iranian government and civil society, and Rouhani must work to empower them. Just as Iran’s oil industry needs the help of international experts and technology to get back up and running, Iran should welcome international assistance from the UN and others when it comes to human rights issues, as opposed to continuing its policy of hostility.

By leveraging the post-deal excitement to encourage human rights reform, Hollande can broaden the scope of France’s bilateral relationship with Iran beyond trade to ensure human rights principles to be ingrained in every aspect of the new relationship. With a more empowered, vibrant Iranian civil society, France’s diplomatic and trade investments would be much more stable as a diversity of voices would be able to check the excesses of the most extreme and hardline political forces.

This week in Paris, the meeting of the two presidents should help rebuild relations following the nuclear agreement. Many issues will surely be on the agenda. For the Iranian people, the question is clear: Will Rouhani’s reconciliation with the EU lead to real protections for free expression, transparent elections, and increased cooperation with the UN and international organization? The answer to this question will depend on Rouhani’s political will, which depends on whether France and the EU prioritize human rights in the new relationship.

Hadi Ghaemi is Executive Director of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.