Discrimination and Inaccessibility Prevent Blind People From Obtaining Employment in Iran

Agency Tasked With Aiding People With Disabilities Fails to Fulfill Mandate

Every October 15 is marked in Iran by White Cane Safety Day, which according to the National Federation of the Blind, is dedicated to raising awareness about safety and independence for people living with blindness and partial sight.

To mark the occasion in 2018, the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) interviewed blind people in several Iranian cities about the obstacles they face obtaining employment despite the passage of laws during the past fourteen years guaranteeing people with disabilities jobs in certain employment sectors.

According to Article 15 of Iran’s Law for the Protection of the Rights of Persons With Disabilities, which was approved by the Guardian Council on April 11, 2018, “The government is required to allocate at least three percent of official and contractual employment opportunities in government agencies, including ministries, organizations, institutions, companies and public and revolutionary organizations, as well as other entities that receive funding from the national budget to qualified persons with disabilities.”

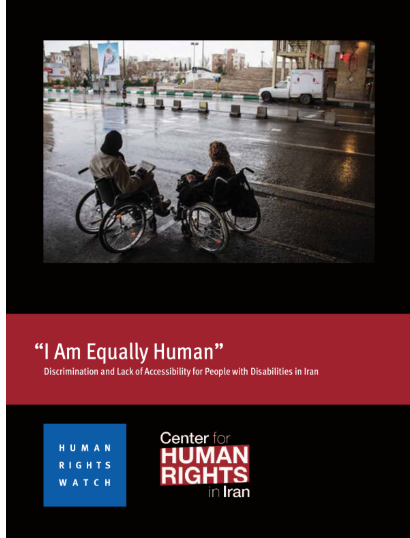

Learn more about the obstacles blind and other people living with disabilities in Iran face on a daily basis in CHRI’s new report co-authored with Human Rights Watch.

Despite an earlier version of this law being ratified by Iran’s Parliament in 2004, the government has still not released any statistics on how the three percent rule is being implemented. Compounding this problem is the lack of accurate statistics on blind people in general.

The government’s lack of a system for compiling statistics about this vulnerable segment of society, such as how many people live in Iran with low vision or blindness, has resulted in officials making wildly different claims about important issues faced by this community, including the employment rate.

For example, on October 14, 2018, Hossein Nahvinejad, the State Welfare Organization’s (SWO) deputy in charge of rehabilitation, said the unemployment rate among blind people in Iran is 40 percent. But in 2017 he had claimed it was 80 percent.

“When there are discrepancies in the statistics about the blind in the country, naturally there will be differences in the unemployment rate,”

Pouya, an Iran-based advocate for the rights of people with disabilities, told CHRI.

“What is certain is that unemployment is very common among the blind and it would be impossible to imagine that half of them found jobs in the past year,” he added.

The individuals who agreed to discuss their experiences for this report requested anonymity to protect their personal security.

Humiliation and Unnecessary Pressure

Blind people in Iran face an array of obstacles obtaining employment, beginning with the lack of reading options for the blind, such as braille, when the job in question requires a written test.

Maryam, a 26-year-old resident of Ahvaz, Khuzestan Province, has a degree in psychology with a specialization on children with disabilities, yet she was treated like she was a nuisance instead of given a fair chance to apply for a job in the Education Ministry:

I mentioned my disability in the employment form but the evaluation test questions were not sent to me in braille due to the carelessness of the officials. On the day of the test, they were very rude to me and asked why I had not informed them of my blindness. I told them I had stated I was in their form. It wasn’t my fault.

Then a secretary there came and read the test questions for me. She had poor knowledge of math and literature and couldn’t read the questions properly so I didn’t mark answers for a lot of them. In the end, she told me to sign my test sheets. I always carry a stamp, which I use instead of signing my name by hand. But for some reason, they didn’t accept my stamp and told me to use a pen to sign my name.

My signature looks like a circle or sometimes like horizontal and vertical lines. But they didn’t accept that either and said I needed to properly sign all the sheets in the same proper way. I still don’t understand why I had to do that. These wrong attitudes humiliate the blind and put unnecessary pressure on them.

Reza, a 23-year-old resident of Rasht, Gilan Province, has a degree in social sciences. He told CHRI that even the SWO, the main agency tasked with providing services to people with disabilities, has not implemented measures that would enable blind people to take employment tests.

“You can even find problems in the employment tests conducted by the SWO, despite it being the top government organ in charge of caring for the disabled,” he said.

“One time I went to the SWO to apply for a job,” added Reza. “They blamed me for not having someone with me to read the questions on the form. They said it wasn’t their job to read the questions for me.”

“If the SWO doesn’t accept us, who will?”

According to Article 11 of the Law for the Protection of the Rights of Persons With Disabilities, 30 percent of telephone operator positions in Iran must go to people who are blind, living with low vision or to people with physical and mobility disabilities.

But Reza told CHRI that not only is this stipulation extremely restrictive, it has also become nearly obsolete due to the fact that most people don’t use phone operators anymore, opting instead for the ease of use of their mobile phones and other digital devices:

“Everybody thinks that a blind person can only be a phone operator. But with the advances in communication networks, there’s no longer a need for phone operators. It has disappeared from the job market for the blind. My friends and I went to look for jobs like marketing, packaging and typing but all the officials politely threw us out. They said we need healthy people.”

On October 14, the SWO’s deputy in charge of rehabilitation claimed there are “about 50 special training centers for the blind” that teach telephone operation and secretarial skills as well as handicrafts. But Reza told CHRI the facilities fail to provide sufficient training that could be applied to existing work opportunities in Iran.

The SWO is not providing any training in mobility directions or classes in areas such as computer science or the English language. Many families do not have high incomes and cannot afford private classes. The SWO has a duty to provide these classes, especially on how to find directions so that when blind go somewhere for work, they know how to navigate without help from others.

Maryam told CHRI that the SWO has refused to step in to enable blind and other people living with disabilities to obtain employment:

I have gone to the SWO office several times and asked officials to find us factory jobs. I even said I would accept all responsibility. We can do packaging operations very well. But they said they were not allowed to interfere in such matters.

My question is: If the SWO cannot step in, and state organizations can easily disregard the law, then why bother legally requiring the three percent allocation of state jobs for people with disabilities?

Since I have a degree in psychology, I asked for a job as an adviser in the social emergency services on an hourly basis. But the official in charge said I was not capable of doing it because I’m blind. If the SWO doesn’t accept us, who will?

Reza told CHRI he had applied at some 30 organizations but that they had all politely, and sometimes disrespectfully, rejected him:

At the state-funded Imam Khomeini Relief Foundation, “a gentleman made fun of me for asking for a job. He said ‘are you really asking for a job?’ I said yes. He said, ‘boy, if I hire you I would have to hire another person just to take you to the bathroom and do your work.’ I told him, ‘didn’t you notice I came here from home by myself? I came from downstairs to your office on my own.’ Then I angrily left.

Iran Fails to Deliver on Domestic and International Commitments

Article 27 of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which was ratified by Iran in 2008, urges member states to remove employment discrimination obstacles and provide job training and accessibility in the workplace for people living with disabilities.

But the people interviewed for this report told CHRI they haven’t seen positive developments beyond the words written on those legal documents.

“The SWO and people with disabilities are concentrating their efforts on implementing the three percent allocation of state jobs but the fact is that attention must also be paid to enhancing the skills of people with disabilities and improve accessibility in their work environment,” disability rights activist Pouya told CHRI.

“For instance, one of my blind friends had been hired by a private company but the ill-informed company officials would not allow him to screen-reader software for the blind on his office computer,” he said. “The question is, how do they expect a blind person to work like his colleagues if they don’t provide enabling capabilities?”