Cleric’s Murder Gives Impetus to Calls for Military Control Over Internet

Authorities’ Focus on Political Activists while Violent Individuals Go Unnoticed on Social Media

Following the killing of Mostafa Ghasemi, a cleric in the city of Hamedan, by an individual who had displayed his violent intentions on his Instagram account, Iran’s security and military establishments have expressed support for Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s demand to impose greater restrictions on the Internet and tighter controls over social media in particular.

Since Nasrollah Pejmanfar, a hardline conservative member of Parliament, and fellow lawmaker Rouhollah Momen-Nasab, one of the strongest proponents of Internet censorship, proposed the “Managing Social Messengers Bill” to the Parliamentary Committee on Cultural Affairs in November 2018, there has been increasing efforts to hand over control of the Internet to Iran’s military.

The killing of Ghasemi has given those efforts greater impetus.

Ghasemi was gunned down in front of a seminary school in Hamedan on April 27, 2019, by Behrouz Hajilooie, who took responsibility for the attack and posted photos of himself with various kinds of guns on Instagram.

Authorities Call for Greater Monitoring of Social Media

According to the BBC Persian Service, Hajilooie had previously talked about carrying out assassinations in his messages on Instagram. He was killed by police in a shootout on April 28.

The same day, Khamenei said in a speech to a group of police chiefs that they should pay closer attention to monitoring content on social media.

“Today cyberspace has widely entered into people’s lives. Despite benefits and interests, it also poses great dangers,” Iran’s leader said.

He added: “The killer of the Hamedani cleric published photos of himself on Instagram carrying four different kinds of guns. Dealing with these matters is the responsibility of the police.”

Reacting to the Iranian leader’s green light for greater control of the Internet, Police Chief General Hossein Ashtari told a conference of police officers on April 29: “Cyberspace has become a platform for the spread of atheism and corruption and in our belief it should be managed.”

Ashtari continued: “Unfortunately we are witnessing growing incidents of crime in cyberspace and, in accordance with our duties, we have issued necessary warnings to relevant authorities.”

“I believe the police have been successful whenever they took well-planned actions in advance and stepped in with access to intelligence. We must therefore expand these strategies,” he added.

Also on April 30, Gen. Bakhshali Kamrani Saleh, the police chief in Hamedan Province, announced the arrest of 32 people who allegedly posted comments in support of Hajiloooie on his Instagram page and added: “several individuals have been identified in Mashhad.”

Authorities Monitor Online Activities of Peaceful Activists, But Not Violent Criminals

The statements by senior police officials have raised concern about the possibility of greater restrictions on social media in the name of fighting crime.

“The guy had 50,000 followers and posted photos with guns and today he killed a mullah in Hamedan. There’s no indication he was ever summoned or convicted. On the other hand, I was sentenced to three months in prison for posting a few critical comments on my page that had 200 followers …” tweeted political activist Siavash Rezaeian.

“I’m a simple activist. Am I under greater surveillance than a killer with a lot of followers?” he added.

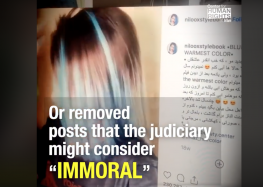

Journalist Jila Baniyaghoob wrote on Twitter: “The FATA cyber police force and certain other agencies were busy monitoring Siavash Rezaeian’s posts and detaining (former secretary of the Defenders of Human Rights Center) Jinous Sobhani over a few strands of hair. They had no time to look at photos of an armed man who openly talked about his assassination plans. If they had spent the time, perhaps the killer and his victim would have been alive right now.”

Passive Defense Organization: Social Media “Incites the People,” Should be Controlled

Meanwhile, on April 28, Gholamreza Jalali, IRGC member and head of the Passive Defense Organization (PDO), which has four divisions responsible for dealing with biological, chemical, radiological and cyberattacks, called for greater control over social media.

“The control of social media networks is a necessity that requires attention,” Jalali said, adding, “In times of crisis, social media networks incite the people against the government and put pressure on the country’s administration. That needs to be controlled.”

On January 21, 2019, the organization had planned to shut off the country’s Internet for two hours supposedly to test the ability of Iranian online banking systems to resist a cyberattack. Although the test was scrapped after widespread opposition by Iranians on social media, it showed the military’s determination to gain access and control Iran’s Internet infrastructure.

Former IRGC member Takes Lead of Key Organization Fighting “Soft War” on Internet

Another step taken to enhance the military’s control over the Internet was Khamenei’s appointment of the former commander-in-chief of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), Mohammad Ali Jafari, to head the IRGC’s Baghiyatollah Cultural and Social Headquarters (BCSH) in April 2019.

The BCSH’s significance stems from its cyber operations. Their role is to help the country address the so-called “soft war” that the West is allegedly waging against Iran on the internet. The fact that its head was directly appointed by Khamenei for the first time is an indication of the importance Iran’s ruling establishment attaches to the “soft war” on the Internet, a topic frequently addressed by Jafari.

“Given your interest in being present in cultural fields and having a role in the soft war… I appoint you to head the BCSH,” Iran’s supreme leader said in his order.

Comments made by high-level officials, appointments to top positions, and actions taken by legislative and executive branches are all signs that the ruling establishment is moving toward imposing tighter restrictions on online activities. Expanding the role of the military and the IRGC in cyber affairs has alarmed defenders of Internet freedom and human rights organizations.

The primary concern is that elected bodies have no oversight of the IRGC, perpetuating the lack of transparency and opening the door to further violations of the law and people’s rights by the IRGC.

During his tenure as commander of the IRGC (2007-2019), Jafari expanded cyber operations focused on the “soft war,” which in December 2016 he described as a the “greatest threat” to the Islamic Republic.

In 2007, Jafari’s first year as commander, the IRGC established the Center for Investigation of Organized Crime, which in 2015 was upgraded to the Cyber Defense Headquarters (CDH).

Gerdab is believed to be the CDH’s official website and it has played a role in suppressing online political and civil dissent, especially following the popular upheavals in 2009. The organization has also carried out several operations to identify and arrest people involved in “indecent” activities such as women’s fashion, female modeling and studio photography.

The operations have put the FATA cyber police force in charge of dealing with online criminal activity.

Jafari’s statements indicate the centrality with which he views this “soft war.” “A lot of people think that the eight-year Holy Defense [Iran-Iraq war] ended [in 1988] but it’s a very important strategic mistake to believe that the war with our enemies is only in the physical realm,” Jafari said to a group of IRGC defense experts on July 24, 2010.

“Today we are engaged in a soft war against the enemies. Their plans, objectives and actions are obvious. But we are not showing the same determination in engaging in this war… We must stop and repulse the soft war before it turns into a physical one,” Jafari added.