Iran Draws “Red Lines” Before Talks With EU on Human Rights

Ahead of high-level talks between Iran and the European Union on human rights, the Foreign Ministry in Tehran has declared certain topics, including the death penalty, off limits. The “red lines” were drawn shortly after a senior member of Iran’s Parliament said the Islamic Republic should accept legitimate criticisms on the issue.

“We have told [the Europeans] that we have certain red lines,” said Deputy Foreign Minister Majid Takht-Ravanchi, on November 11, 2016, referencing the bilateral talks that he said could take place in “the next two or three weeks” and could last “two, three or even four years.”

“When the topic of executions comes up, we will tell them that the death penalty is part of our laws. Edicts in the Quran (Islamic sacred book) are not something we can just put aside. That’s impossible. This is clear to us and clear to them. Other than that, there are some topics that can be debated in order to bring our views closer,” he added.

Last month an official admitted that the death penalty could become a campaign issue in Iran’s 2017 presidential election. “We’re having presidential elections in eight months and it’s important that [executions] will not turn into a political issue,” the head of the Judiciary’s Human Rights Council, Mohammad Javad Larijani, told a Brazilian newspaper on October 6.

Death Penalty Debate

The vast majority of executions in Iran are for drug-related crimes, but despite Takht-Ravanchi’s comment, the Quran does not recommend the death penalty as punishment. Human rights organizations and civil rights activists have strongly criticized the Islamic Republic for having one of the highest execution rates in the world. While hardliners have vehemently resisted reform, some members of the political establishment are showing signs that they may be open to change.

“The Europeans might have some criticisms about human rights violations in Iran, and in my view, some of them are true,” said the Parliament’s Deputy Speaker Ali Motahhari, during an interview with the semi-official Iranian Labor News Agency on November 12.

“Regarding human rights, there are some concerns that [the Europeans] may interfere in our affairs,” he continued. “There are two issues here. One is that Islamic laws are not negotiable. On the other hand, there are common human affairs that have nothing to do with any particular ideology.”

“We must accept legitimate criticisms on human rights. At the same time, we must also monitor human rights issues in Europe where there are many violations. So it goes both ways. They will be watching us and we will be watching them and voicing our concerns, too… What’s important is that we should accept fair criticism and avoid being stubborn,” he added.

The unprecedented display of openness to Western criticism by a conservative MP coincides with an ongoing debate in the country between MPs and the Judiciary over the effectiveness of executing hundreds of petty drug traffickers every year.

“The large majority of those who have been executed or are on death row are petty drug dealers who are first-time offenders, and their deaths harm families,” said Jalil Rahimi Jahanabadi, a member of Parliament’s Legal and Judicial Affairs Committee, on October 4 after announcing that a majority of MPs support limiting the death penalty to bigger crimes.

“In essence, we are proposing to add an amendment to the current law for fighting drugs which states that the death penalty would apply if certain conditions are met, such as carrying and using a gun, or being an international drug kingpin, or having a commuted death sentence and repeating the crime,” he added.

“There a lot of people waiting to be hanged right now and the question is whether all these executions carried out so far have stopped the spread of drugs or not? If there haven’t been any benefits, we need to think of alternative punishments,” he said.

In his September 2016 report, former UN Special Rapporteur Ahmed Shaheed estimated that there were between 966 and 1,054 executions in Iran in 2015 according to human rights organizations—“the highest number in 20 years.” More than 90 percent of the executions in the country are drug-related, according to Mohammad Javad Larijani, who on October 8 for the first time expressed support for limiting executions.

“I am in favor of changing the law, but that does not mean we should stop the fight against drug-trafficking,” said Larijani, the brother of Judiciary Chief Sadegh Larijani, who strongly supports the death penalty.

“Naturally, executions are not an ideal solution, but we need to act quickly and firmly against harms to society and the destruction of families [caused by drugs],” said Sadegh Larijani on September 29. “I ask prosecutors across the country to carry out executions as soon as the verdicts are issued.”

However, the Judiciary chief’s hardline position seems to be losing ground within the government as more officials question the efficacy of executing hundreds of people every year for petty drug crimes.

“We are looking to see what punishments can replace executions with greater effectiveness for certain criminals. Of course, the death penalty will still be enforced, but not to the extent we have today,” said Justice Minister Mostafa Pourmohammadi—who is by no means a moderate—on October 29.

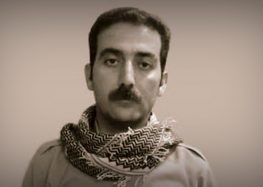

In addition to the death penalty, the Iranian delegation will likely be questioned by the Europeans over their treatment of civil rights activists, including prominent human rights activist Narges Mohammadi, who has been sentenced to 16 years in prison in part for her opposition to the death penalty.