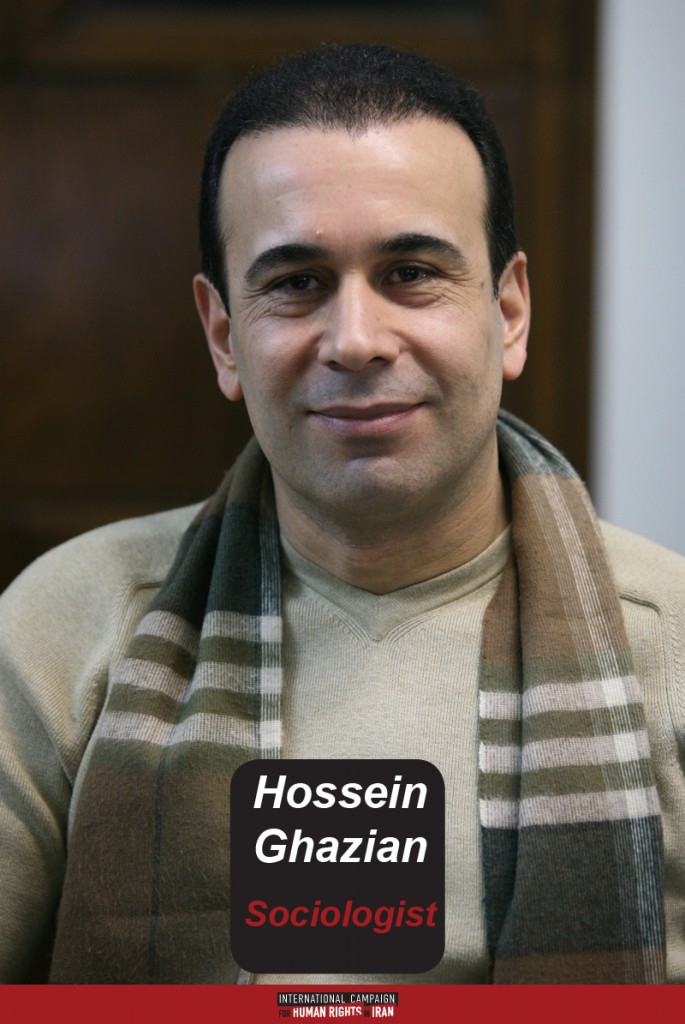

Commentary: Iran’s Lonely Islamic Laws

Hossein Ghazian, a sociologist and researcher of Iranian politics, gender, and culture, specializes in social gauging and measurement, and specifically in surveys. Dr. Ghazian has also been a journalist for more than 20 years. He has authored several books and has published numerous articles on sociology and Iran. This is the first of a series of articles by Dr. Ghazian that will be published by the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, focusing on themes of human rights and sociology, and analyzing policies related to these subjects.

By Hossein Ghazian, Sociologist

Commentary: In his most recent reaction to the third report by UN Special Rapporteur for human rights in Iran Ahmed Shaheed the Head of Iran’s Judiciary states that the report is “a violation of Islamic laws.” In order to disagree with Ahmed Shaheed’s report, Ayatollah Sadeq Larijani uses a two-pronged approach. First, he begs other Islamic countries for help, and then, for those people who feel ambivalent towards Islamic laws, he tries to agitate them into feeling offended.

Mr. Larijani says that human rights reports like this one in fact seek to “close down Islamic laws” in our country. He tries to portray this demand to “close down Islamic laws” as a threat that is not limited only to Iran, but also affects all Islamic countries. In other words, he warns Islamic countries that while human rights monitoring may be a predicament Iran is facing now, sooner or later it will come knocking on their doors, too. But as Islamic countries have not yet been moved by such warnings or punishment, it is doubtful that this same rhetoric would move them, assuming they hear it at all.

But why? Why don’t the other Islamic countries support the Islamic Republic of Iran, a country that wishes to establish Islamic laws? Why does Iran feel alone when it comes to Islam?

A simple reason could be that these other Islamic countries, the ones that are begged by our Ayatollahs, are not that Islamic, or are not Islamic in the way that the Ayatollahs would think or wish. From among 57 member states of the Islamic Countries Conference, only a few base their penal codes exactly on Islamic laws. For example, the punishment of stoning is only enforced in a few Islamic countries, and only sporadically at that, and usually away from the eyes of the media and public opinion. Aside from stoning, Mr. Sadeq Larijani is probably better qualified to tell us in how many Islamic countries sentences like hand and foot amputations, throwing a person from great height, or gouging eyes by throwing acid are carried out.

And these are only some very violent laws. What about other, not-so-violent laws? How many of these countries, for example, have forced hijab laws, or laws governing citizens’ eating and drinking? Even putting aside these laws governing normal life, how many heads of Islamic states can you find who would refuse to shake hands when introduced to women? Even Saudi rulers, who have not abandoned stoning and beheading, do not hesitate to shake hands with women. Perhaps if these countries weren’t facing pressure from their strong tribal traditions, they would not have any reason to behead or amputate the hands of thieves at all. Conversely, if our rulers did not have to face international public opinion and human rights reports like Ahmed Shaheed’s, perhaps they would not hesitate to carry out those sentences and worse. Both sets of political leaders submit to enforcing or not enforcing these laws because their political power is intertwined with their observation or lack of observation of these laws. In other words, keeping and continuing political power is more important in these cases than Islamic considerations.

When only a few Islamic countries enforce Islamic laws in practice, one might pose the question of what is left of their “being Islamic.” Whatever is left, it is not enough to encourage them to enforce Islamic laws, at least not according to their present day Iranian interpretation. Whatever is left, it is not enough to move them to enforce these laws knowing the opposition of international public opinion—an opposition that, good or bad, is a result of the domination of human rights discourse in today’s world. And whatever is left, it is not enough to force them to support the Islamic Republic of Iran, which violates human rights while claiming to enforce Islamic laws. This is why today’s Iran also faces a type of Islamic loneliness.

This loneliness is not only formed on a foundation of historical and traditional differences between Shi’a traditions versus the rest of the Islamic world’s mostly Sunni beliefs, but also on the very tradition’s outdated nature in today’s human rights–affected world, opposed by those who wish to live in up-to-date ways. This loneliness becomes more palpable considering the Islamic Republic believes itself to be the center and leader of the Islamic world. As far as Islamic laws are concerned, it appears that this leadership does not go outside the boundaries of Iran.

The problem is that Iran’s Islamic loneliness is not limited to the Islamic world. This loneliness has somehow also gripped the regime inside Iran itself. The Ayatollah overseeing the branch that deals with justice and fairness, the one through whose fingers the crime statistics run, and who can observe to what extent the nation violates Islamic laws, knows better than the rest of us that in Iran, not too many people are concerned about whether or not the laws are Islamic, at least not as much as whether their desire to see justice and fairness is met. Therefore, it appears Mr. Larijani can feel that his forays into the area of “closing down of Islamic laws” will not produce any tears from his internal audience. This is why he uses another trick, one that works better in the case of our easily excitable society.

He adds that human rights organizations in fact demand that we not execute “drug traffickers” and “sex offenders.” He knows well that when he mentions these groups of suspects, the people’s revenge-seeking blood boils hotter than when he talks about the “closing down of Islamic laws.” It seems he knows that aspects of human rights violations have their roots in the society’s unrelieved need for revenge, in a society where the citizens remain undecided about the deaths of others. This is the same current that runs under the very skin of Iranian society and emboldens its rulers towards violence and death. And it is this violence and death that brings temporary relief and is recounted as a manifestation of human rights violations in human rights reports.