10 Years Later, This Baha’i Manufacturer is Still Fighting to Claim His Business in Iran

Payam Vali’s manufacturing business was shuttered in Iran in 2008 because of his religious beliefs.

Payam Vali’s eyeglass lens manufacturing business in the Iranian city of Karaj was shuttered by the authorities in 2008 because of his religious beliefs. Ten years later, he’s still fighting to get it back.

“I have gone through all the legal channels,” he told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) on May 28, 2018. “If the judiciary does not respond to my complaints, there’s not much more I can do other than to ask Parliament’s Article 90 Commission to investigate violations of the law by the judicial authorities.”

The Iranian Parliament’s Article 90 Commission is charged with investigating public complaints regarding Parliament, the Executive

Branch and the Judiciary, and can send inspectors to conduct investigations to deal with such complaints.

However, the efficacy of the Article 90 Commission as a public grievance mechanism is limited by the fact that it has no real enforcement capabilities. Moreover, its track record has been mixed; while at times it has served in an investigative capacity, its activities are dependent upon the political proclivities of its members at any given time.

The judiciary has also not proven to be particularly responsive to the Article 90 Commission’s questions or criticism in the past.

Vali told CHRI that he has been prevented from running a business despite holding a license from the Ministry of Labor to operate as a lens crafter.

“Ten years ago, six lens crafting shops in the Nazarabad district were shut down,” he said. “Five of them belonged to Baha’is. The only one who continued to operate was a Muslim.”

“After they sealed my shop, I wasn’t working for nine months and I went to various government offices every day from eight in the morning to two in the afternoon to follow up on my case,” he added.

“Then my financial situation got very bad and I had to start another business selling cosmetic and health products. But they stopped me from doing that, too,” Vali said.

He continued: “I was supplying products to skin specialists in Karaj. After six months, one of the best dermatologists was summoned by the provincial health office and he got lectured for two hours by several Intelligence Ministry agents who ordered him to stop ordering my products. They told him Baha’is are politically corrupt, which is a lie.”

“So they used this tactic to gradually ruin my second business, too,” said Vali. “Little by little, it became harder to work as word spread to other skin specialists who naturally became scared of doing business with us. Eventually, we couldn’t continue the business and I have been practically without work for two years.”

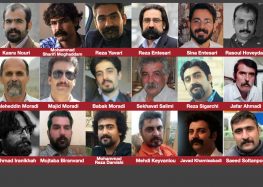

In May 2018, the Baha’i International Community (BIC) at the United Nations expressed alarm over a spate of arrests of Baha’i faith members in three Iranian provinces by agents of the Intelligence Ministry.

Iran’s Constitution does not recognize the Baha’i faith as an official religion. Although Article 23 states that “no one may be molested or taken to task simply for holding a certain belief,” followers of the faith are denied many basic rights as one of the most severely persecuted religious minorities in the country.

In November 2016, dozens of Baha’i-owned shops across Iran were shuttered while their owners briefly closed them down to honor the birthdays of two of the faith’s holiest figures.

Vali told CHRI that when he complained to the Administrative Justice Court about the closure of his business, he was told he must make a pledge to the Intelligence Ministry not to convert Muslims to the Baha’i religion.

“I told the judge that we are constantly being accused of things like spying… and as a citizen I have the right to defend my reputation and to tell the people that these accusations are without foundation and violate my rights as a citizen,” Vali said.

“We are the same as followers of any other religion,” he added. “But when we defend ourselves based on our constitutional rights, they try to hide their shame by accusing us of ‘propaganda against the state.’”

Despite decades of international condemnation of their discriminatory behavior, Iranian leaders—particularly the country’s supreme leader, Ali Khamenei—have justified the continued persecution of Baha’is by describing them as “unclean” and even forbidding Muslims from shaking hands with members of the faith.

Vali also told CHRI that anti-Baha’i propaganda led to the death of his brother.

“The slanderous attacks against Baha’is during all these years resulted in the death of my 12-year-old brother on June 9, 1990,” he said.

“Three months before it happened, a cleric came to our village mosque near Nazarabad and started spreading hatred against Baha’is and said anyone who spills the blood of a Baha’i, his sins will be forgiven and will go to heaven,” explained Vali. “I was 10-years old at the time and I heard these things from my Muslim classmates.”

“I didn’t understand that the people were being psychologically brain-washed to attack Baha’is,” he added. “Then, three months later, my brother went missing and his body was found in a well. The climate was very much against Baha’is at the time and my father decided not to take the case to court.”