Campaign Report on Human Rights in Iran since 12 June 2009 – Accelerating Slide into Dictatorship

21 September 2009

Accelerating Slide into Dictatorship

Human Rights in Iran since 12 June 2009

———————————-

Violations of Citizens’ Rights

Killing of Peaceful Demonstrators by Government Forces

Arbitrary Arrests and Disappearances

Torture and Ill-Treatment of Detainees

Violations of Freedom of Expression and Information

Violation of the Obligation to Protect Human Rights Defenders

Appendix — Testimony of Ebrahim Sharifi

———————————-

Introduction

Human rights in Iran have deteriorated precipitously for over four years, since the onset of the administration of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. But since the disputed presidential election on 12 June 2009, Iran’s slide into dictatorship has sharply accelerated.

For the past four years, the government has increasingly cracked down on dissent; persecuted women’s rights activists seeking to end discriminatory legislation; denied labor activists their international right to organize; restricted the freedom of expression; persecuted student activists; arrested and otherwise persecuted members of religious minorities; tortured political defendants and convicted them in unfair trials; denied minorities their cultural rights; and executed more prisoners in absolute terms than any other country except China, including juvenile offenders. The government has shut down human rights organizations and arrested and imprisoned human rights defenders.

These developments occurred in the context of the militarization of the government bringing it under control of intelligence structures and the Revolutionary Guards, as well as the manipulation of the Judiciary by intelligence and security agencies. To provide a pretext for the repression of human rights and civil society and its own escalating arrogation of power, the Ahmadinejad government has stoked international tensions in an attempt to stir nationalistic feelings and support for itself by conflict with members of the international community.

In order to retain power, and before the eyes of the world, political authority in Iran has been allowed to be hijacked by military, intelligence and security forces, which have tried to violently crush the movement for freedom, democracy, human rights, and normalization of international relations.

Ayatollah Syed Ali Khamane’i, who had, until the elections, been viewed as an arbitrator of power between different political factions, has become a political partisan through his unwavering support of Ahmadinejad’s government and his policies in the post election era.

In the aftermath of the disputed 12 June election, hundreds of thousands of Iranians publicly protested what they said was massive fraud in counting the ballots. These protests were numerous and largely peaceful. On June 19, Ayatollah Khamane’i, who as the commander in chief is responsible for the actions of the security forces, the Revolutionary Guards, and the Basij militia, threatened the protestors with use of force if they did not desist.

Over the following days, government forces confronted demonstrators with excessive and sometimes lethal force, leading to dozens of deaths, hundreds of injuries and at least 4,000 arbitrary detentions. The government has recently publicized mass trials in which prominent reformists and others read confessions that bore every sign of being coerced, and the Campaign have gathered testimonies that confirm allegations of widespread torture and rape of persons in detention.

This brief report details how an accelerating slide into dictatorship has been accomplished by the grave violation of Iran’s international human rights obligations.

Violations of Iranian citizens’ right to freedom of association and freedom of assembly, protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) as well as the Iranian Constitution (Art. 27)

Following the disputed 12 June elections, Iranian authorities banned peaceful demonstrations in Iran’s main cities including Tehran, Shiraz, Isfahan, Tabriz, Mashad and Rasht, as well as elsewhere, to protest electoral fraud and to demand human rights. Security and intelligence forces as well as Basiji militias on motorcycles brutally attacked demonstrators, using batons, tear-gas, pepper-spray, water cannon, chains, and live ammunition and plastic bullets, killing an as yet undetermined number of them. The use of force against demonstrators has been excessive, unlawful, and in gross violation of the standards contained in the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force by Law Enforcement Officers upheld by the UN General Assembly. Many victims were killed or gravely injured by gunshots or blows to the head, which is to say, intentionally. Security agents have arrested injured demonstrators when they sought medical treatment in hospitals.

Iran’s Leader, Ayatollah Khamane’i demanded an end to demonstrations and threatened to hold opposition candidates responsible for any problems. Others among Iran’s highest religious and political authorities announced a policy of criminalizing dissent, which can have lethal consequences, given Iran’s excessive use of the death penalty and lack of independent courts. Ayatollah Khatami, an influential hard-line cleric, has demanded that demonstrators be considered “enemies of God (Mohareb),” guilty of crimes under Iran’s Islamic legal code for which they can be executed. Iran’s Leader has also demeaned protesters, terming them “rioters” and has thus legitimated harsh punishment of those who have been detained on the basis of their political views and for exercising their right to freedom of assembly and to peacefully demonstrate their views.

Despite these threats, hundreds of thousands of Iranian citizens peacefully demonstrated on several occasions including 20 June, 9 July, to commemorate student demonstrations ten years earlier, on 17 July, at Friday Prayers, and on other dates. The gatherings were met with severe violence by the authorities, resulting in hundreds of arrests and injuries and numerous killings.

The Mayor of Tehran, Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, estimated that three million persons have taken part in demonstrations on 20 June.

An unknown but apparently large number of peaceful demonstrators have been killed by government forces and militia in the course of demonstrations

Iranian authorities assert that approximately 30 persons have died in the course of events since the 12 June elections, but several forms of evidence point to a much larger figure. To date, a lack of transparency and manipulation of information by government authorities has obscured the truth. Authorities have threatened family members against discussing injuries and deaths of victims, and in some cases forced families to claim their loved ones died of natural causes. Investigations by political organizations and NGOs have been forcibly thwarted and halted.

The authorities have repeatedly used excessive, lethal force, which has led to the death of persons who were not even involved in demonstrations. For example, Basiji militiamen have been documented by photographs and videos firing at crowds from atop buildings. Massive volleys of gunfire against protesters were witnessed on 14 June, 20 June, 9 July, and on other dates. Ten students were killed on 14 June in attacks in Isfahan, Tabriz, and Tehran. Medical professionals with access to the records of morgues of three hospitals have reported that 34 bodies of demonstrators were deposited in one day, and some of the bodies reportedly showed multiple bullet wounds.

Families of disappeared persons seeking information from the authorities have been shown albums of photographs of the dead reportedly containing hundreds of photographs, and some have reported seeing “hundreds” of corpses in makeshift morgues. Many bodies were reportedly buried in anonymous graves in Behesht Zahra cemetery overnight.

A number of detainees have died from wounds they received, either before or after their arrest, while they have been in custody. The body of Mohsen Ruholamini, the son of a supporter of unsuccessful presidential candidate Mohsen Rezai, was returned to his family reportedly bearing marks of torture and ill-treatment. The authorities claimed he died of meningitis. Amin Javadifar, a student detained on 9 July, also reportedly died in detention.

Ramin Qahremani, 30, was tortured in prison and his body was delivered to his family recently. According to the Norooz website, he was arrested in his home after agents identified him from a bank security camera. He was kept in prison and tortured for 10 days before being released. He told his mother that for several days he was suspended from his feet. He was taken to the hospital a few days before being released for internal bleeding in his chest. Ramin’s body was buried under the supervision of the police forces.

Taraneh Mousavi was arrested on 28 June near the Masjed Ghoba. She was reported as disappeared for several weeks and finally her burned body was found near Ghazvin. It was reported that she was severely sexually abused while she was in detention. Her case was revealed by reformist presidential candidate Mehdi Karroubi, but his information was denied by State authorities. Mohammad Kamrani, 18, was arrested in Tehran on 9 July 2009 and was transferred first to Kahrizak detention center and later to Evin prison. On 15 July 2009, his family was informed that he was in Evin prison and was transferred to the Loghman hospital under guard control. As he received no treatment there, and was simply left handcuffed to the bed, his family obtained permission to transfer him to Mehr hospital, where he died on 16 July from severe injuries. Hamid Madah Shourche, a member of the Mousavi presidential campaign in Mashad, was arrested while he was protesting at Goharshad Mosque. He was tortured and died several days after his release, in the first week of July, because of brain damage. Pouya Maghsoud Baygi, a medical student in Kermanshah, was arrested on 20 June by Intelligence forces in Kermanshah, and died because of the severity of his torture in the prison.

The number of dead has been claimed by Iranian opposition researchers at around 73.

In the 50 days after the 12 June presidential elections, Iran executed 115 convicted prisoners, according to Amnesty International. The authorities have provided no detailed information about who many of these persons were, and what crimes they allegedly committed. This “alarming spike” in executions is considered a warning to dissidents, who may be charged with crimes for which they could face capital punishment.

———————————-

Arbitrary arrests, disappearances, and detentions including incommunicado detention; unfiar trials; disregard for due process

On 11 August, the Judiciary’s spokesperson, Alireza Jamshidi, announced that around 4000 citizens have been arrested and detained since the elections. About 400 people are believed to be in detention as of this writing.

A large number were ordinary people who were taken into custody as they participated in peaceful demonstrations. The authorities also arrested hundreds of opposition figures, journalists, human rights lawyers and activists, intellectuals, and professors, and students including prominent former members of the government. The Campaign has compiled a list of about 240 of those detained who were arrested in the first 10 days after the election. While some of them were released on heavy bail, others who had been ordered released on bail and paid the required sums were not released, including Mohammad Ghouchani, journalist. The families of some detainees could not pay the high bails demanded, as high as $500,000 (500 million toman) and such detainees, including for example Shiva Nazarahari, had to remain in jail. However, the detentions continue, and have included three grandsons of Grand Ayatolah Montazeri, who has openly criticized the abuse of citizens’ rights, and son of Ayatolah Mousavi Tabrizi. On September 17, at least four well-known people were arrested, including, Sayed Mehdi Mousavinejad, the brother-in-law of Ali Abtahi, a former vice president also in detention; Mehdi Mahmoudian, human rights activist and a member of the reformist Iran Participation Front; Mehdi Mirdamadi, son of Mohsen Mirdamadi, General secretary of Iran Participation Front , who is in prison; and Hossein Nourinezhad, the head of public outreach of Iran Participation Front.

Following mass trials, many detainees have had no access to their families and lawyers and still are in solitary confinement, including for example Mustafa Tajzadeh and Abdollah Ramezanzadeh. The first information available about Abdullah Momeni since his arrest on 21 June, and confirmation that he was even alive, was his appearance at the mass trial on 13 September.

Due process violations have accompanied all arrests. Arrests have been made with no warrants or other court documents being presented, or documents that gave authorities carte blanche to arrest anyone; they have often been made late in the night or very early in the morning and family have been abused in the process; arrests have been made by plain-clothes agents presenting no identification; personal property has sometimes been damaged or confiscated; and detainees have been taken to unknown locations, essentiallydisappeared.

Arrests have in a number of cases threatened the lives of the detainees: Seed Hajjarian, a detained reformist political figure, suffers from severe physical problems as a result of an assassination attempt in 2001, and needs special care 24 hours a day; a journalist in detention; Ebrahim Yazdi, a former Foreign Minister, was arrested and taken into detention while in the intensive care unit of a hospital. Dr. Mohammad Maleki, who was arrested while he was under treatment for prostate cancer, wasn’t able to walk and two agents helped him to the car. He needs special injections and conditions for his treatment that cannot be found in prison. According to the report published by the Committee to Investigate Arbitrary Detentions, many detainees arrested after 12 June suffer serious health problems, including Behzad Nabavi who had open heart surgery before his arrest. Abdullah Momeni and Isa Saharkhiz also suffer serious health problems.

Many of those detained are reportedly held in solitary confinement and in incommunicado detention. They have been prevented from contact with families, friends, or lawyers. Detentions have been extended without legal justification.

The government has not released a comprehensive list of those detained and their whereabouts, nor has it announced what charges detained persons face, leaving many hundreds of family members in a state of high anxiety; as indicated above, the charges may carry death sentences. Cases have been documented in which officials have willfully misled family members seeking information about missing relatives, and concealing the fact that such persons were dead. The large number of unaccounted for persons raises fears about torture and also that many of the missing are dead.

Among those detained are several foreign nationals, including Kian Tajbakhsh, an Iranian-American social scientist, who is still in prison, Maziar Bahari, an Iranian-Canadian journalist.

Human Rights Watch and FIDH expressed concern about the appointment of Iranian prosecutor Saeed Mortazavi, who has been asked to investigate and prosecute detained reform leaders. Mortazavi has been implicated by the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detentions for involvement in a range of grave human rights violations. He was subsequently removed from the position and appointed as a deputy of the national general prosecutor.

The mass trials of those detained for political reasons have been widely condemned for being “show trials” completely at variance with international standards of due process, and in violation of Iranian law. Defense lawyers have been denied access to their client’s files, and have not been informed about which courts would consider their cases. Lawyers have informed the Campaign that in some cases, defendants have been given court-appointed lawyers without informing their own attorneys.

———————————-

Torture and ill-treatment of detainees

There have been credible reports of torture and ill-treatment including inter alia rape, beatings, and sleep deprivation aimed at confirming the government’s claims that protests have been orchestrated by foreign governments or terrorist organizations.

For example, Ahmad Zaidabadi, the director of the Advar Tahkim Organization and a prominent journalist, was detained on 13 June at his home. A person posing as a delivery man lured him out of his house and unidentified agents kidnapped and took him away. In protest against the illegal manner of his detention, the lack of charges against him, and the conditions of his detention, Zaidabadi was on a hunger strike during the first 17 days of his detention.

His wife, Mahdieh Mohammadi, was able to visit him only after 65 days of having no access to him. During their visit, Zaidabadi told her that he had spent 35 days in solitary confinement, in total isolation, where there was no sound, no light, and no human contact. He told her he felt like he was in a grave, developing serious mental disorientation, and becoming suicidal. Since he could not find any means for committing suicide, he started to scream nonstop. The prison guards eventually realized that he is on the verge of insanity and transferred him to a different solitary cell. During the visit, Zaidabadi told his wife that interrogators had asked him to give guarantees that he would never engage in political activism, although they had not formally charged him.

Amnesty International has reported that Mostafa Tajzadeh, Abdollah Ramezanzadeh and Mohsen Aminzadeh, all imprisoned supporters of opposition candidate Moussavi, are reported to have undergone “intensive interrogation” sessions in Tehran’s Evin prison. Ramazanzadeh, the spokesperson in Khatami’s cabinet, was arrested on 13 June in the street when he was seriously beaten, causing injuries to his head and rib cage. Since his detention, he has not been charged and the location of his imprisonment remains unknown. After 74 days of detention, Ramezanzadeh was brought to the mass trials in which he asked journalists to tell his family that he was fine. Up to that date, his family had no information about his situation.

The Campaign has received information indicating that other prisoners, about whom no information is available about their legal situation, have suffered beatings and other ill-treatment, including Keyvan Samimi a journalist and human rights defender. Keyvan Samimi was arrested at the midnight of 14 June while Security Forces broke into his house and confiscated his personal computer and belongs. According to his lawyer, Nasrin Sotudeh, she visited him for the first time on 10 September in presence of his interrogator. He told that her that he was beaten twice and the prison doctor certified that the sign of torture was seen on his left leg. Sotudeh also has said that she has had no access to his file, but during the visit, he and his interrogator informed her that he was charged with membership in the illegal groups including, the National Religious Coalition, the National Peace Council, and the Committee to Investigate Arbitrary Detentions.

“Confessions” by detainees aired on state television have led associates and family members to allege that they could only have been obtained under coercion. The large number of persons held in incommunicado detention, and in unknown locations, leads to fears about torture and ill-treatment especially in consideration of the very widespread use of torture to produce confessions in Iranian trials, which are often the only evidence upon which defendants are convicted.

Students and many of ordinary prisoners were tortured severely, and there are credible reports of sexual abuse. Fifty students arrested on 14 June were taken to the basement of the Interior Ministry, four levels underground. According to information received by the Campaign, they were tortured en route to the facility and once there. Packed into a small room, they were reportedly beaten with batons if they touched one another. They were beaten and humiliated if they used toilets for more than 30 seconds. The students were reportedly sexually tortured.

The Campaign has been informed that as many as 100 cases of rape have been filed privately with the Speaker of the Parliament, Ali Larijani, but he has dismissed them all as false.

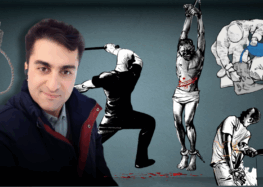

Ebrahim Sharifi, 24 years old student in Tehran, was kidnapped by plainclothes agents on 22 June by plainclothes agents for one week. He provided detailed testimony to the Campaign regarding his torture and rape during detention. He said he was subjected to severe beatings, mock executions, and sexual assault. When he attempted to file a judicial complaint and told several judicial authorities what happened, intelligence agents threatened him and his family, forcing him into hiding. Sharifi’s full account is detailed in the appendix of this report.

Another charge of rape was reported to the Campaign, in which a female detainee was raped in one of the prisons in north part of Iran. One of the members of an opposition election campaign was forced to accept that he had had sexual relationships with 10 women who were active in the campaign, and he refused. Suddenly, his female colleague was brought into the room and raped in front of the others. Both have now been released, but the rape victim suffers severe depression.

Violations of freedom of expression and information

Since the disputed elections, Iran has arrested and detained over 30 journalists and photographers. Numerous journalists from opposition media have been detained including 20 from Kalemeh Sabz alone.

Bahman Ahmad Amouiee, a journalist and women’s rights defender, was arrested along with his wife, Zhila Baniyaghoub, a journalist, in his home on 20 June 2009. Amouiee is deprived access to his lawyer as well as his family. His lawyer has no access to his file. After 70 days in detention, he had a very short phone call to his wife and said that Judge Mortezavi was in charge of his case. He said that his interrogation had ended and his case was referred to the court, but he didn’t know which branch was in charge. On 31 September, prison officials informed Zhila Baniyagoub , who was released recently, that Amouiee is banned from having visitors.

Mohammad Ghouchani, a journalist and editor in charge of Etemad Meli daily was arrested after presidential contender Karoubi’s letter to the Guardian Council was published on 20 June 2009. Ghouchani was ordered to release on bail on 23 August and the release letter was issued. Maryam Baghi, his wife, in an interview on 6 September said that after his release letter was issued he was transferred to solitary confinement on 27 August and later to ward number 240 in Evin prison and was under sever interrogation. As of this writing he is in ward 209. He is charged with “participation in illegal gatherings to endanger national security,” and “writing articles instigating unrest.” However, his family has said that he was not present in any demonstrations and during the weeks after the election he had not authored any articles. In his most recent call to his family, as of this writing, he told them that despite the order to release him on bail, interrogations have been resumed and he is under tremendous pressure to make false confessions. His interrogators have told him he will not be released unless he makes a confession.

Issa Saharkhiz, a journalist and a founder of the Association to Defend Press Freedom, was arrested on 3 July 2009. He spent 40 days in solitary confinement in the Revolutionary Guard prison in Tehran. Nasrin Sotoudeh, his lawyer, was able to visit him after 40 days and informed that his rib cage was broken. Sahar Khiz suffers high blood pressure and allergies and requires a special diet and he is not able to take any medications. His temporary detention order has been renewed for another two months.

The office of the Journalists Association was closed by order of the Tehran Prosecutor without any explanation on 5 August, the Day of Journalists, while the Association was preparing to hold its general assembly.

More than 300 journalists wrote a letter on 8 September to Tehran Prosecutor and requested the release of detained journalists and respect for the freedom of the press. Many were immediately summoned and threatened. They were asked to withdraw their signature and cooperate with the Intelligence services to name those who wrote the letter and collected the signatures. About 15 of them were ordered to stay in Tehran and were banned from travelling.

A number of foreign journalists have been expelled from Iran and prohibited from reporting the events, and in some cases Iranian official media and authorities have accused foreign journalists of inciting unrest, at the behest of the government of the United Kingdom.

A Greek journalist for the US-based Washington Times, Iason Athanasiadis, was detained and ill-treated.

Foreign journalists have been prohibited from observing protest demonstrations and other important events. Websites and phone lines have been blocked on several occasions, preventing the circulation of information on the elections and the post-elections situation in the country. Foreign news broadcasts have been jammed.

Private social networking websites have been used to persecute individuals and their associates. The authorities shut down such sites, including Facebook, for periods of time. Mobile telephone networks have been shut down on election day, which was meant to prevent sharing election-monitoring information.

Violations of the obligation to protect human rights defenders

Human rights defenders including human rights lawyers have been targeted for arrest since 12 June and a number have been taken into custody. Plain-clothes agents arrested three members of the Defenders of Human Rights Centre (DHRC), including lawyer Abdolfattah Soltani, who was arrested by persons posing as clients; lawyer Mohammed Ali Dadkhah, and M. Abdolreza Tajik. Soltani is also a member of the Committee to Investigate Arbitrary Detentions; other members of the Committee who have been detained include Alireza Tajik and Kayvan Samimi. Colleagues of Mohammad Ali Dadkhah arrested along with him included Malihe Dadkhah (his daughter), Sara Sabaghian, Bahareh Dowaloo, and Amir Raiisian. All of these lawyers, prior to their arrest, represented numerous individuals who had been detained since 12 June. All were subsequently released.

One member of the Committee to Investigate on Arbitrary Detentions, Kayvan Samimi, remains in prison and no official information was released about on him, although it was reported that he was tortured severely. According to the Committee spokesperson, Hasan Asadi Zaydabadi, six members of the Committee have been summoned several times and requested to shut down the group, stop issuing press statements, and cease visiting the families of detainees.

Shiva Nazarahari, a human rights activist and editor in charge of the web site of the Committee for Human Rights, was arrested on 14 June at her office. The night before intelligence agents had gone to her home and searched everywhere and took her personal belongings. She spent 36 days in solitary confinement in ward 209 in Evin prison and was reportedly tortured to confess to what the interrogators wanted. In September, she was ordered to be released on $500,000 bail, which her family wasn’t able to afford, and she remains in prison. Recently, the bail was reduced to $200,000, which still too high for her family to afford. On 17 September, her lawyer and family finally received permission to visit her. She informed them that her interrogator had told her that she won’t be released even if the bail is posted.

The DHRC, founded by Nobel Peace Laureate Shirin Ebadi and others, has been closed since December 2008, when it was shut down by Iranian authorities. Ms. Ebadi has come under renewed threat, as media close to the government published a letter claiming to have been written by war veterans and the families of martyrs as well as experts, in which they demanded that legal proceeding be brought against Ebadi for allegedly violating the law in the course of her human rights advocacy (since 12 June, Ms. Ebadi has undertaken urgent missions to leading international officials to convey concerns about human rights violations in Iran and request engagement by the international community). The threatening letter is considered a signal that Ebadi can face prosecution in Iran.

———————————-

Appendix : Testimony of Ebrahim Sharifi

Ebrahim Sharifi, was kidnapped by plainclothes agents on 22 June by plainclothes agents for one week. He provided detailed testimony to the Campaign regarding his torture and rape during detention:

My name is Ebrahim Sharifi, born on 27 February 1985, 24 years old and a computer science major at Azad University in Tehran. Before the 12 June elections I was active in a grassroots campaign office for presidential candidate Mehdi Karroubi. I did campaigning by doing graphics work, making posters and distributing them. After the elections, believing the result were not true, I participated daily in protests. In many of the protests, security and intelligence agents took my pictures and videotaped me, which I did not mind.

On the evening of June 22, as I was on my home, in Kangan Boulevard, a black car pulled over next me. A middle aged man, perhaps 40-45 years old, wearing a grey suit, seated in the passenger sit called me over. As I approached the car, a third person from behind grabbed me, twisted my hand behind my back, put on plastic handcuffs, blindfolded me and threw me into the back seat and pushed my head down. I felt a period of about 40 minutes passed before we stopped at a place where there was no more sound of cars. They pushed me like a lamb into what felt like a large hall. I was still blindfolded and handcuffed. I could hear the heavy sounds of others breathing.

That night I felt asleep handcuffed and blindfolded. I was not given any food or drinks. Some people would ask to be taken to a bathroom but no one would come. The next day, the sounds of a girl in pain and screaming were heard. I and others started protesting. In response, someone came in and said we have to be collectively punished. They took out our clothes, leaving on my underclothes and threw me on the floor. I thought there were 30-40 other detainees in the room. I was still handcuffed and blindfolded. They started beating me and others on the back with some kind of a whip. It was thick and elastic. The person was whipping me and four other people, because I was counting. He would whip each person three times and then move on to the next and repeat the cycle. He was doing this for hours and was getting tired as the interval between each whipping became longer and longer. My mouth was close to the ground and I could smell urine and blood.

Afterwards, more hours past, I don’t know how many, until someone came in and put some kind of relieving cream on my back. I was exhausted and passed out. Until the next day we were not given any food or drinks. I don’t know how long I was asleep that someone came in and pulled me up, holding me under my shoulders. They ordered us to line up and said we have been condemned to execution. I had heard many stories of fake executions, but still was gripped in fear. They took us to an outdoor space; it must have been early morning as I felt a morning breeze. They put a rope around my neck and said your execution order has been issued verbally, you are charged with being Mofsed fi-al Arz (corrupt on earth), and we are waiting for the written order to come. I felt an hour passed like this, until someone came and announced, “For now the Leader has pardoned you, get lost.”

I was taken back to the big hall. They took off my handcuffs and gave us a few pieces of stale bread and potatoes and a glass of water that tasted awful. In the following days, I was subjected to mock executions twice more. During the last instance, I protested by saying if you want to hang me why don’t you just do it? Why all these games? Someone came forward and hit me hard in the stomach. I fell down and he continued to keep hitting me in the stomach till I was throwing up blood. He told someone else, “Take this –expletive- and impregnate him.” The other person dragged me on the floor to another room as I was very weak. In there, he tied my hands to a handcuff that was connected to the wall, tied my feet, and pulled down my underwear. He then said “If you can’t protect your –expletive- how do you want to bring about a Velvet Revolution?” He then sexually assaulted me. I was feeling so weak and became unconscious.

When I gained consciousness, I was no longer blindfolded and was lying on a bed and tied to it with metal handcuffs. It looked like a clinic. In the bed next to me was another person who screamed nonstop; a medical worker, probably a nurse or a doctor, would came by frequently and inject him with a serum. I was constantly throwing up blood. About 16 or 17 hours passed like this. In these circumstances, someone came and stood behind my bed and told the medical staff: “Doctor, he is dying or should we finish him off ourselves?” I heard the doctor’s voice responding: “He is in terrible shape. He could cause us lots of trouble like the other two. Just get rid of him.”

A few more hours passed. They untied me from the bed, blindfolded me again and put on the plastic handcuffs. Then they asked my name and phone number. I think they took me back to the detention hall. From there they led me to a car and drove me off for about 10-15 minutes. They stopped and led me out of the car still blindfolded. They told me to count to 60 and then take off my blindfolds. I was on Sabalan Highway. It was morning time. I managed to walk to a supermarket and call a friend who came and picked me up and took me home. My mother couldn’t believe I was alive; she thought I had been killed.

The next day, the first thing I did was to go to a psychologist. I also talked to several lawyers and friends who recommended I file a judicial law suit. I went to the judiciary office in Elahieh and wrote up a complaint about being kidnapped. The authorities told me it is not within their jurisdiction and I should go to the Revolutionary Court. I went there but they repeated the same thing. I went to the criminal court and they wrote a letter to the Police Detective Bureau to investigate the case. From there I took the letter to the First Bureau of Detectives in Niavaran. There, the authorities told me it doesn’t relate to them and I should go to the Central Detectives Bureau in Shapour and Mowlawi intersection. I went there and the staff there asked me for the report of my disappearance that my father had filed. I told them it is filed with the First Bureau of Detectives, so they sent me back there. At the First Detectives Bureau they told me, “We cannot release your file to you,” so I returned to the Central Detective Bureau.

Finally, the authorities there stamped my letter saying the relevant crime is kidnapping and asked me to go to Branch 11 of police detective bureau . First they asked me to come back the next day, but I insisted that the signs of torture and my beatings were starting to go away and I wanted to give a testimony now. A detective eventually agreed to interview me. He told me it is probably the work of the Ministry.” I asked which Ministry and he replied: “The Intelligence ministry. If I were you I wouldn’t follow it up.” I insisted that I wanted to follow up and want to be examined by a state-certified physician. He eventually agreed and wrote a letter to the office of state-certified medical office. When I went there, they said I should return the next day. I went back but they kept making excuses and wouldn’t examine me. I finally realized they are not willing to examine me.

A week passed and I finally decided to go meet with Mr. Karroubi. I went to his offices and told him my entire saga. He asked me to provide my testimony to Judiciary officials. Tehran’s prosecutor’s office contacted me and said they want to expedite my complaint. But then suddenly out of the blue, the official asked me, “What is your expectation from Karroubi?” I responded I don’t want anything from him.

On 19 August, I met with Mr. Mohammadi, the representative of Dorri Najaf-Abadi, the country’s General Prosecutor and I gave him my testimony. The next day, Mr. Moghaddami, the representative of Mr. Moratazivi, Tehran’s general prosecutor contacted Mr. Karroubi that Mortazavi has asked to meet with all witnesses. At 2 p.m. on 20 August, I went to Mr. Karroubi’s office and met with Mr. Moghaddami. He asked me to write down my entire testimony and I did so. Then he started asking me questions that were irrelevant to my detention and what had happened to me. He said how can we know you haven’t been paid by Karroubi to make these allegations? I was very surprised. These insinuations were repeated multiple times by Moghaddami.

He then sent me to the state-certified medical offices for examinations. The doctor there told me with nearly two months having past since the occurrence of the sexual assault, there will be no visible signs by now.

During this period, several judiciary agents had combed through my neighborhood, talking to local shopkeepers and our neighbors, collecting information about me.

On 23 August, I was due to meet with a group of parliamentarians and to provide them my testimony. That day, on the street, a car approached me and pulled over. It was a Peugeot and the driver called me over. He claimed to be a friend of my father and spoke very warmly of him and had so many details about my family; I was persuaded he is an old family friend. He offered to give me a ride. He drove me from Niavaran towards Darabad. In the car he suddenly warned me, “Look, if you give testimony to the parliamentary committee, you and your entire family will be killed in a staged accident. You know we are capable of doing it.” I was shocked that he was aware of my imminent meeting and realized he is an intelligence agent.

I left the car and realized that my family and I are in great danger, because while there is no will within the Judiciary to investigate my case, there are much efforts to intimidate me and my family into silence and to make false accusations that I have been paid by Karroubi to make up my story. I immediately went into hiding. Subsequently my father was threatened. I left the country and since then my friends and associates have been under pressure to denounce me. Some of them have been called into the Intelligence Ministry and interrogated for hours. I fear for my family and friends’ safety in Iran.