Abdol-Karim Lahidji: Judiciary’s Intimidation Tactics and Disproportionate Punishments Marks Its Failure to Deliver Public Justice

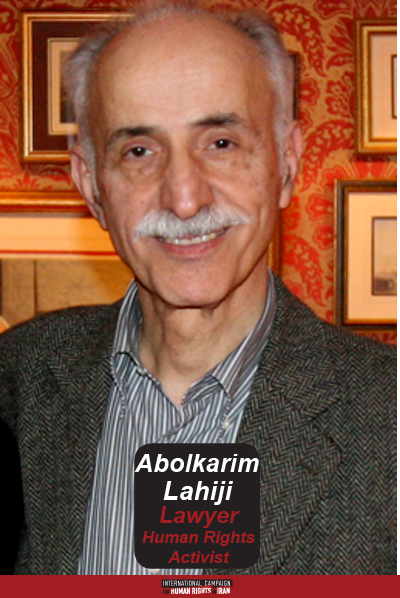

In an interview with the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, prominent France-based lawyer and human rights activist Abdol-Karim Lahidji said that the experience of the past three decades proves that increasing punishment levels have not led to a decrease in crime rates nor to the establishment of security in the society.

Following the announcement of death sentences for two men who were charged with violating public security through “robbery,” prominent lawyer and Vice President of the International Federation of Human Rights (IFHR) Abdol-Karim Lahidji told the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran that the main focus of the Iranian Judiciary’s penal policies is on increasing the punishment levels and acting selectively vis à vis judicial cases. Lahidji believes that this policy is a vehicle of suppression, employed by the regime to eliminate its dissidents, and that the duality would lead to ineffectiveness of these policies, elimination of security from the society, and deprivation of the Iranian nation of their minimum social and political rights.

On December 1, 2012, a surveillance video was released on YouTube in which four young men on motorcycles, armed with a dagger, attacked a pedestrian on a Tehran street and robbed him of his briefcase before the eyes of other pedestrians. One of them also hit the victim in the face with the dagger and fled the scene. The four men were tried on January 2, and two of them were sentenced to death on charges of offending public sensibilities.

On January 2, the lower court proceedings for the four suspects in the “robbery case” were held at Branch 15 of the Tehran Revolutionary Court under Judge Abolghassem Salavati. Two of the suspects were sentenced to death and the two others were sentenced to 10 years in prison, 5 years in exile, and 74 lashes. Judge Salavati is the same judge who presided over the show trials of political and civil activists after the 2009 election, and is one of the judges known for his long prison and execution sentences.

Failure of the Judiciary’s Penal Policies

In an interview with the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, prominent France-based lawyer and human rights activist Abdol-Karim Lahidji said that the experience of the past three decades proves that increasing punishment levels have not led to a decrease in crime rates nor to the establishment of security in the society.

“A government’s penal policies cannot be only based on severe action and increasing punishment. For example, in the area of the war on drugs over the past three decades, an increase in the number of executions and an increase in the drug-related crimes indicate that this policy has failed, as hundreds of annual executions not only have not curbed the drug trafficking and its related crimes in Iran, the crime rate has increased many times. Execution statistics extracted by human rights organizations through what is published in Iranian newspapers, which may not even include all the executions carried out in Iranian prisons, indicate that the number of executions in Iran has grown between two and three times. Officials from the Islamic Republic of Iran themselves admit that 70% of these executions are drug-related. When increasing the punishment does not decrease the crime rate, it means that it is not possible to combat that crime with the intensified punishment. There are social, economic, and political factors that lead to the commitment of crimes, and so long as those elements remain present and they are not dealt with, it is obvious that crime and offense statistics will not only cease in the society, but they will increase daily,” Lahidji said.

Referring to the selective treatment of offenders by the Iranian Judiciary, the IFHR Vice President said that the selective treatment is one of the reasons for the loss of pubic trust in the Judiciary. “In some cases where the topic of economic corruption comes up and the Iranian authorities are forced to talk about it—that is when they talk about individuals who have embezzled billions of public assets, and in some cases they are even reporting execution sentences for some of them—we observe that the perpetrators enjoy so much security, support, and backing that their identities are not even exposed in court. In most cases they are only introduced by their initials, such as ‘G.K.’ It is apparent that these individuals rely on political and economic backing within the regime. This even includes sex crimes. A while back they said that several individuals were sentenced to death on sex-related offenses and they were subsequently executed in public squares. It is the same way for murder cases. Conversely, from the moment political suspects are arrested, they create a negative atmosphere around them, they fabricate cases against them, and invent crimes for them, and quickly issue heavy sentences for them,” Lahidji said.

“In the Islamic Republic, the penal policies are based on creating fear and intimidation in society. For example, in the case of political prisoners the punishment is to create fear and horror, so that people can see that the price for political activities, or participating in social activities, or even defending political suspects (for example in the case of my lawyer colleagues) is no longer three and six months in prison, but 6 years and 10 years and 13 years, and to refrain from such activities. They issued very heavy sentences in the cases of our colleagues, like Nasrin Sotoudeh, Abdolfattah Soltani, and Mohammad Ali Dadkhah. The policy the Islamic Republic has adopted and which has intensified over the past several years is sure not to lead to any results, and they will not be able to combat factors that lead to crimes in Iran,” he explained.

Show Programs: Ambiguity in Kahrizak Case Four Years On, and Sattar Beheshti’s Case

“After the Kahrizak events, with all that noise and propaganda, and even after the father of one of the victims went to see [Supreme Leader] Ali Khamenei and he ordered an investigation, after four years they are now saying that trials of the culprits will begin, and three judges, including Saeed Mortazavi (former Tehran Prosecutor) who were involved in these events are going to be put on trial. Or, recently, in the case of the young blogger, Sattar Beheshti, who, it was determined, died under torture, only last week a report by the National Security Commission was read at the Parliament, and two MPs said that the report had been censored. Now, with all the noisy propaganda aimed at gaining a good reputation for the Judiciary—which unfortunately is a nest of corruption itself—and, as they claim, to heal the people’s feelings, they inform us of rapid review of a case such as the unsafe streets. All this happens under circumstances where people see that the Judiciary, as a source of justice in the country, is itself a corrupt entity and is used as a tool of suppression and political goals in the hands of the government to eliminate its political dissidents,” Abdol-Karim Lahidji told the Campaign.

With more than four decades of experience in legal affairs and human rights, Abdol-Karim Lahidji spoke candidly about the present “security” situation of the country. “There is no security in Iranian society. Before, murders would happen in people’s homes, but now they rob people on the street. They take ransom and attack people with daggers and weapons that are a lot more dangerous than the ones used before. Now, officials in charge of security think that by creating such noisy propaganda, they can create fear in the hearts of criminals and those contemplating committing a crime, and assure people that the government and the Judiciary are in control of the situation, and that soon the perpetrators will be punished, hoping to reduce the air of lack of security through propaganda programs. But in my opinion they will not succeed. In Iran, people have no security vis à vis the government itself, the security-intelligence organizations, and other [state] entities. . . . Because a major part of the IRGC [Revolutionary Guards], the police, and the Intelligence Ministry is corruption-ridden, they can never combat crime,” said Lahidji.

“Basically, in the new Iranian Penal Code, meaning the one implemented post-Islamic Revolution, there is no legal requirement for the punishment to be proportionate to the crime. Though they say there is an article in the new Penal Code, the titles are so general, they can be abused or misinterpreted very easily,” said Lahidji about charges such as “moharebeh” (enmity with God) for individuals who threaten public security on the streets, or “moharebeh” and death sentences for drug-related crimes.

The Robbers and the Blogger: Both Acting Against National Security!

“During the first few years after the Revolution, [authorities] killed thousands of people under general charges such as ‘moharebeh’ or ‘corruption on earth,’” Abdol-Karim Lahidji told the Campaign. “Since they imported such titles into the Islamic Penal Code, they have interpreted these general concepts in whatever way they have chosen. What is the meaning of ‘moharebeh’? Does ‘moharebeh’ mean that when someone uses a dagger to attack people, it would be considered the same as taking up arms against God or the Islamic Republic? The same thing goes for ‘corruption on earth.’ Or consider the charge of ‘acting against national security’ in the case of political crimes. It means that opposing the government is ‘acting against security.’ Acting against security is the type of crime these robbers are committing against the people on the street. They are depriving the public from security, and endangering security. But when a blogger writes something, how can he compromise public and national security and jeopardize security?” he added.

“The authorities have imported some general concepts into the Islamic penal Code, and they have made them available to a group who, as judges, lack sufficient legal training, as well as independence. . . . Mr. Shahroudi, the former Head of the Judiciary, said that when he took over the Judiciary from his predecessor Mohammad Yazdi, it had been in ruins. Mr. Shahroudi further deteriorated the branch and then delivered it to Mr. Larijani. Over the past few years, [Mr. Larijani] has in effect taken the Judiciary to a level where the rulings have broken records of severity and frequency of sentences. Therefore, there is no such thing as proportion between the crimes and their punishment, the way it is stipulated in a modern penal code. Separating crimes and assuring their overall compatibility with the extent of the crime are neither carefully foreseen in the law, nor in action. This is why you will observe that first they may arrest someone on charges of espionage. Then they request the death sentence for him. Ultimately we will see the suspect sentenced to six months in prison, and if he is a foreigner, he will be released to return to his country. Of course that’s good, but I’m trying to say that there has never been any proportion between the crime and the punishment in the Islamic Republic of Iran, because as I said, the Judiciary neither has independence, nor specialist employees who would have the necessary moral requirements for employment in a judicial position. Overall, this is the cause of the current situation they have caused for public security, rights, and freedom,” Lahidji concluded.