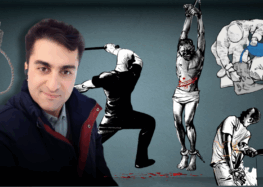

Iranian Morality Police Arrest Popular Underground Musician Amir Tataloo

Popular rapper Amir Tataloo’s songs have great appeal among Iranian audiences; he has 560,000 fans on his Facebook page.

Iran’s Morality Police have arrested popular rapper Amir Tataloo. Colonel Massoud Zahedian, Chief of the Morality Police, told ISNA that his unit is actively identifying and confronting Iranian underground musicians who produce their work inside Iran and distribute it on television satellite channels abroad. Zahedian added that following the arrest, Tataloo is now in custody of the Iranian Judiciary.

Since the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iranian musicians have needed government authorization in order to play their music, hold concerts, and produce music albums and videos. Government scrutiny of such musical activities and productions has been stringent, and only certain genres of music receive production and activity licenses.

It is illegal for musicians to perform without government authorization, and there have been numerous reports of arrests of Iranian musicians who have performed their music without a license. The arrests have taken place in recording studios, on underground stages, and even while no musical activities have been in progress.

Even when musical groups are issued concert licenses, there is no guarantee that they can safely hold their scheduled appearances. At an August concert of Dawn of Rage, an Iranian metal band, all the musicians and the 200 guests attending the concert were arrested at a public amphitheater in Tehran. The Dawn of Rage band’s concert was authorized and as such well-publicized. According to Rooz Online, members of the audience who were released later told a friend that the forces made them take off their clothes so they could be inspected for “devil worship tattoos” on their bodies, confiscated their cell phones, and photographed them prior to their release. “Devil worshipping” is an accusation frequently used against Iranian rockers on state media and conservative publications.

The ban on musical activities is not limited to heavy metal or rock music. A large group of Iranian musicians who had risen to fame prior to the Islamic Revolution were banned from musical activities after the 1979 revolution. Kourosh Yaghmaei, a very popular pre-1979 pop musician, recently wrote about a 25-year ban on his musical activities on his website and on his Facebook page:

“Generally, for 25 years of the past 35 years since the [1979] Revolution, I have been banned from my profession, and I am banned at this time…. When your punishment is to become banned from your profession, there is no time limit…. I still don’t know why I am banned from working. For my first ruling, which lasted 17 years, my image was banned from the media and I was even banned from foreign travel … but for the second period which has now lasted nine years, I have not yet been able to find an answer. A ruling has been issued in secret, because if it were a legal ruling, it should have been announced explicitly and clearly. But it appears there was no plaintiff and no defendant, and no crime had taken place; there was no trial court and no judicial process including lawyers and judges and a jury, and there was no verdict. But the amazing thing is that a ruling was issued behind closed doors, and it was carried out, without stipulating a time limit…. How long? No one is accountable.”

The Morality Police Chief did not disclose why many Iranian musicians have been unable to secure authorization for their musical activities. “Thank God both IRIB [state radio and television] and the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance have provided the necessary groundwork for artistic activities, and individuals who intend to be active underground must abandon these efforts and continue their activities within legal and real frameworks,” he said.

Iranian musician Mohsen Namjoo, who now lives in exile in the US, described the rationale of the Iranian censors who denied him a license when he lived in Iran. In a piece for Sketches of Iran, a book published by the International Campaign or Human Rights in Iran in January 2013, Namjoo wrote:

“[O]n three different occasions I went to the Council of Experts at the Ministry of Islamic Guidance as a composer. They would listen to the music and the minute my voice came on, they would stop the music and ask me what kind of music it was…. One of the Council members told me, ‘The reason we don’t issue you a permit is that we don’t know what you are doing. We don’t know what is happening in this music!’ He told me explicitly that if they were to give me a publishing license for my album and after its release it turned out that I was trying to make a mockery of the very foundations of traditional Persian music, and one of the top authorities complained about it, he could lose his job.”