Gender Segregation Violates the Rights of Women in Iran

Commentary by Leila Mouri*

The recent sharp exchange during a press conference between Morteza Talai, Deputy Chairperson of the Tehran City Council, and a female journalist from Sharq newspapers over Talai’s support of a recent gender-segregation initiative in the Municipality of Tehran, reflects the intensifying struggle between hardliners intent on controlling the domestic sphere and more moderate elements of Iranian society who resist relinquishing their basic rights.

The initiative separates men and women’s offices in the municipality and limits women’s access to managerial and clerical positions. Talai, who was clearly angered by the journalist’s persistent criticism of the policy, accused her of “compromising her dignity.” The incident received considerable attention by the media inside and outside Iran as the latest manifestation of hardliners’ recent measures to enforce more conservative rules in the country and regulate women’s presence in the public sphere.

Since the 1979 revolution, the Iranian government has been enforcing gender segregation regulations in certain public spaces such as schools (from primary to high school), sports centers, and public transportation. Although there is not comprehensive nationwide legislation regarding gender segregation in Iran, various organizations have adopted internal rules to ensure it is observed. When Mahmoud Ahmadinejad came to power in 2005, gender segregation gained more attention by the authorities.

In 2011, his administration formed The Committee of Protection of Modesty and Hijab to draft a series of regulations which would enforce their interpretation of modesty in public spaces, which included gender segregation in workplaces. However, the policy was not enforced and many governmental and non-governmental offices did not adopt it. However, during the last few weeks, gender segregation has again turned into a leading issue, with the decision by Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf, the mayor of Tehran, to order the separation of his male and female employees in the municipality.

Ghalibaf’s decision is facing strong opposition by progressive journalists, civil and women’s activists, and officials such as Shahindokht Molaverdi, Vice President of Women’s Affairs in Rouhani’s cabinet. She criticized Ghalibaf’s initiative and explicitly asserted that the administration does not approve of gender segregation in the workplace. Ghalibaf’s comments also angered social media users on Facebook and Twitter, who expressed their dissatisfaction and ridiculed the move.

To date, however, despite the fact that this policy has the potential to profoundly affect the livelihood of all women across Iran who work in various governmental offices, there has not been a significant outcry beyond these largely liberal and middle class segments of society.

In a speech at Tehran Friday prayers, Ghalibaf defended his decree in the name of dignity and Islamic discipline. He said: “We are an Islamic system and have a religious dignity and we should not let unrelated men and women intermingle [in the workplace] more than they spend time with their family members.”

He also claimed that gender segregation is for the good of Iranian women and that they support his segregation projects. Ghalibaf’s actions and remarks were welcomed by Iranian hardliners who control the Parliament, the Judiciary, and the intelligence and security organizations. This widespread power grants hardliners an upper hand in pursuing their conservative agenda in domestic affairs, despite the large electoral victory of the more centrist Rouhani.

The extent to which other municipalities will follow Tehran’s model is as yet unclear. The municipality of Ardabil in Northwestern Iran, known for the religiosity of its residents, also ordered the separation of men and women in the workplace. The mayor of Ardabil argued that this arrangement would increase efficiency and security in the organization.

However, in Mashhad, one of Iran’s major cities and the site of one of its most sacred Shiite shrines, a City Council member brushed away the idea and told reporters that “the Council has not approved any such policy as of yet.” In the absence of an institutionalized policy, gender-segregation is usually enforced locally and arbitrarily, and in most cases it is solely based on decisions taken by the head of an organization.

At the time the segregation initiative was introduced, it was reported that Tehran’s municipality dismissed an unidentified number of female employees holding secretarial and managerial positions, all of whom were to be replaced by male personnel. Farzad Khalafi, Media Affairs Deputy of Tehran’s Municipality, told reporters that management is a “time consuming and lengthy job” and therefore this was “for the comfort and well-being of the women”.

Though it is not known how many employees were dismissed, the number of women potentially affected is great: the Municipality of Tehran’s website states it has 8,275 female employees (14.9% of all employees). Mohammad Taqi Hosseini, the Deputy of Minister of Labor, criticized the dismissal of female employees in an official letter and called it “discrimination based on gender,” and against international conventions, but he did not directly question the segregation policy.

Despite Rouhani’s position opposing discrimination against female employees and gender segregation, his administration has largely refrained from taking on the hardliners on gender issues. It is unclear whether this reflects fear of a harsh backlash from the hardliners and thus unwillingness to confront them, or simply a preference to concentrate for now on what they see as the more pressing issue of moving forward with the P5+1 nuclear negotiations. Regardless, there has been little challenge to the conservatives’ violations of the civil rights of Iranian citizens.

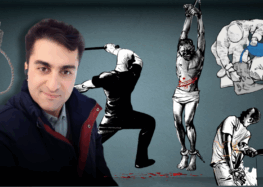

Gender segregation regulations during the past 35 years have been a pretext to deprive Iranian women of access to high-ranking positions, such as the presidency and judgeships. Women are also barred from attending certain public spaces such as sports stadiums. During the last few years, hardliners have also limited women’s access to higher education institutions and programs.

In 2012, the state excluded women from 77 majors in specific universities, including management, mathematics, physics, and computer engineering. Shirin Ebadi, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate, condemned the measure as “part of the recent policy of the Islamic Republic, which tries to return women to the private domain inside the home as it cannot tolerate their passionate presence in the public arena.”

Women and men’s mingling in public and private spheres has also been a concern for the government since the 1979 revolution, although the level of enforcement has ebbed and flowed depending on the administration, reflecting the lack of comprehensive institutionalized legislation on the matter.

The police have regularly raided private parties to arrest young men and women solely for having a mixed gathering. Questioning men and women’s relationship on the streets by morality police (a branch of security forces co-directed by the Revolutionary Guards and Interior Ministry) and arresting them if not related has been a common phenomenon.

Iranian conservatives’ recent concentration on social and cultural issues such as gender segregation in the middle of the ongoing political and economic crises faced by the country is seen by many as a reaction to Hassan Rouhani: while hardliners have not been able to prevent Rouhani’s foreign policy initiatives and his efforts to improve the country’s relations with the West, they are determined not to lose their power to their moderate opponents in the domestic sphere.

As such they seek to secure their dominance over interior affairs by implementing more conservative policies. It is yet to be seen whether Rouhani’s administration will take concrete and meaningful steps against such measures. If not, women across Iran will pay the price of these violations of their basic rights.

——

**Women’s Rights Activist and Journalist