Introduction

This study presents the views of a cross-section of Iranian civil society on the effects of the outcome of the nuclear negotiations on the people of Iran. These negotiations between the P5+1 countries and the Islamic Republic on the future of Iran’s nuclear program, set to conclude June 30, 2015, will determine whether sanctions and the international isolation of Iran are maintained. Their success or failure, as this study shows, is of momentous importance to the Iranian citizenry.

Download the report here.

After eight years of living under the Ahmadinejad administration, a period marked by economic mismanagement, rampant corruption, and repressive governance, and then enduring the toughest sanctions regime that the international community as imposed on a country to date, it is not surprising that the news of an interim nuclear agreement in April 2015 was greeted in Iran with cheering crowds pouring into the streets to celebrate.

Yet this is also a nation scarred by the preceding decade and disillusioned by two years of little change under a president who was elected on a platform of reform. As a result, the views of Iranian society—their hopes, expectations, and doubts regarding the actual effects of the outcome of the negotiations for ordinary Iranians —are quite nuanced and measured.

This study by the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran, in which a broad spectrum of members of Iranian civil society were questioned in depth on their perceptions of the negotiation’s effects inside Iran, presents those views.

The study confirmed that Iranian civil society’s support for the nuclear negotiations has remained unequivocal and unanimous since the Campaign’s July 2014 study of society’s views on the P5+1 talks. Indeed, the potential for a negotiated end to the conflict over Iran’s nuclear program—and thus an aversion of war and an end to the country’s international isolation—has brought a profound sense of collective hope to the nation.

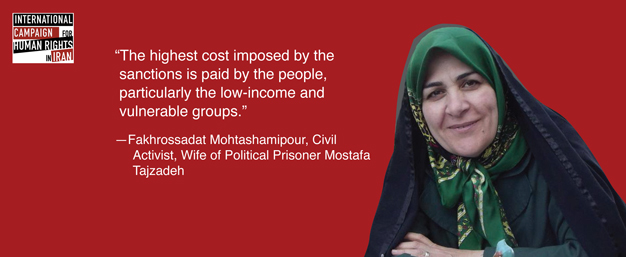

The view that sanctions and international isolation have been profoundly destructive for Iran not only economically, but in virtually all other spheres of life—politically, socially, and culturally—was also unanimous among the interviewees.

All of the respondents were particularly emphatic that a failure to reach a negotiated settlement to the nuclear conflict—and thus a continuation of sanctions and Iran’s international isolation—would be catastrophic for Iranian society. Debilitating economic deterioration, increased political and cultural repression, and potential for war were consistently cited as expected results of such an outcome.

Beyond that, however, there was noticeable uncertainty and divergent views regarding the effects of a negotiated settlement on Iran’s economy, and on political and cultural freedoms in the country.

In contrast to the Campaign’s July 2014 study which gauged support among civil society in Iran for the nuclear negotiations at that time, views have clearly undergone a subtle but perceptible shift. While there is remarkable consistency and consensus on the gains that need to be realized in a post-deal environment—economic revitalization, increased civil and political rights, greater social and cultural freedoms—there are increasingly divergent views and doubts regarding the likelihood of any of these changes actually happening, Indeed, for many, there is a growing gulf between what they hope for and what they expect.

For some, this reflects growing concern over President Rouhani’s two-year record in office, in which little changed in the lives of ordinary Iranians and hardliners successfully initiated crackdowns on press freedoms and Internet activities, imposed long prison sentences on peaceful activists, and passed legislation highly discriminatory toward women.

Some are content to wait, accepting the argument of “the nuclear file first,” and many still predict that if an accord is reached there will be significant gains to society with a newly empowered and energized Rouhani.

Yet even among this group, there are growing signs of impatience, and a sense that things have been “put on hold” for far too long. Many respondents stressed that if an accord is signed, the time will have come for Rouhani to bring his focus home and act.

For others, there was a significant amount of skepticism regarding any benefits of a deal to society at large, and growing doubts that an end to sanctions will bring meaningful changes to people’s daily lives. Respondents often questioned Rouhani’s ability to act. They doubted the administration had the managerial competency to shepherd the country toward economic health. Even more frequently, they noted his lack of authority to confront the real centers of power, which have no such intention of allowing reforms.

Rampant corruption, an issue that has dominated social media discussions and the domestic press in Iran, was often mentioned in this regard, with respondents asserting that any economic gains would be captured by corrupt and opaque centers of state power.

Others questioned Rouhani’s willingness to enact change, noting with dismay little action during the last two years even in areas under his direct authority.

Thus as much as the interviewees were unanimous in wanting deal, hoping for a deal, and knowing the myriad problems that should be addressed in a post-deal environment, they were notably divided on their expectations. Deep consensus on the outcome of failure in the negotiations was paired with little consensus on the outcome of success.

Nevertheless, side-by-side with such fears and doubts was palpable and residing hope. Many of the respondents, even those most skeptical of a post-deal environment, spoke of this hope. Evident throughout these interviews is a nation longing for a relief from the threat of war, thirsty for re-engaging with the world, and eagerly anticipating the prospect of ending Iran’s isolation, even without any other tangible benefits to daily lives and pocket books. This hope has seemed to bring the first cracks of light into a collective consciousness that has been remarkably black for years.