Imprisoned Reformist Iranian Journalist Hospitalized After Prolonged Hunger Strike

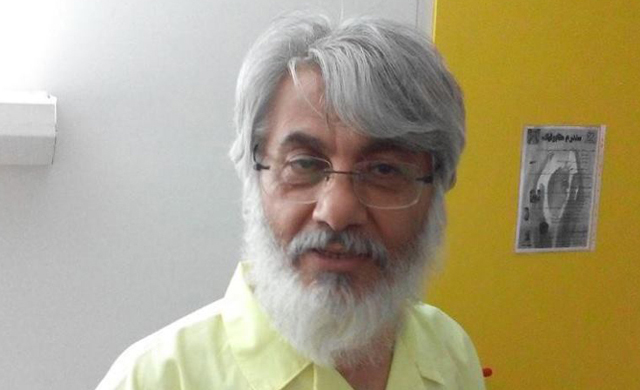

Issa Saharkhiz, imprisoned reformist journalist and former political prisoner, was hospitalized on March 9, 2016 due to life-threatening health deterioration from successive hunger strikes.

“My father has lost more than 20 kilograms. My family says he looks like someone entirely different. It is natural for anyone to develop severe problems and weight loss after some time on hunger strike,” Saharkhiz’s son, Mehdi Saharkhiz, told the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.

Issa Saharkhiz described the inhumane conditions he has suffered since his November 1, 2015 arrest in a letter from prison published on March 8.

“I was often locked up in a solitary cell which is a form of ‘white torture’ [psychological and mental torture]. Even when someone else shared a cell with me, it was just to look after me, as, due to various reasons and different illnesses, I have repeatedly fallen down in the room, the bathrooms, the courtyard, during fresh air breaks, etc., due to a severe drop in my blood pressure and poor blood circulation to my brain,” he wrote.

Solitary confinement is a common tactic used in Iran to increase psychological pressure on a prisoner to extract a false confession. Such “confessions” are then used as evidence to convict—and frequently broadcast over Iran’s state TV in order to defame the individual.

Saharkhiz ended his latest hunger strike, which had lasted two weeks, on March 7 after he was transferred from solitary confinement inside Evin Prison’s Ward 2-A—controlled by the Revolutionary Guards’ Intelligence Organization—to Ward 8. Saharkhiz has protested his detention and inhumane conditions by enduring three hunger strikes since his arrest.

“I also had severe seizures a few times. After three-and-a-half months, and only on orders from the representative of the Legal Medicine Organization, was I transferred to the infirmary at Evin Prison,” wrote Saharkhiz. “I have not received even a simple electroencephalogram (EEG) for diagnosis of this new, unknown condition. Naturally, when a medical examination which is critical to a prisoner’s health is neglected, the prisoner’s other rights are also neglected.”

Political prisoners in Iran are singled out for particularly harsh prison treatment, which often includes denial of medical care.

Issa Saharkhiz’s letter was published on his son Mehdi’s Facebook and Twitter accounts on March 8.

“It is clear they have a personal vendetta against my father; otherwise they would not treat a human being like this. Even a murderer would not be treated like this,” Mehdi Saharkhiz told the Campaign. “Saeed Mortazavi [former Tehran Prosecutor] who is even accused of murder, was released on a small bond, and he is comfortably walking on Tehran streets. The Judiciary is kind to those who flatter it, and treats those who criticize it very inhumanely.”

Agents from the Revolutionary Guard’s Intelligence Organization arrested Issa Saharkhiz, a political activist and well-known reformist journalist, on November 1, 2015.

Charged with “assembly and collusion for acting against national security,” and “propaganda against the state,” Saharkhiz was scheduled to appear before Branch 28 of the Tehran Revolutionary Courts on March 5, 2016. But because his lawyers had not been allowed access to his case until trial day, they requested a postponement.

Saharkhiz wrote that he has been denied access to a towel, toothbrush, and toothpaste. He added that he has also been denied access to state television, newspapers, and even religious books such as the Quran, and that his only contact with the outside world is a state radio broadcasted into his cell.

Saharkhiz said he has been arrested for his journalistic work: “If I have committed a crime, it is of a journalistic nature, and whatever the court is using as evidence and which has been reflected in my indictment is based on my writings.”

He also pointed out that according to Article 168 of the Iranian constitution, political and press-related crimes must be tried in the presence of a jury.

“It is clear that such charges do not need detention, especially not an illegal detention for more than four months, and it is necessary for the detention orders to be cancelled immediately—a point I continuously made to the case experts [interrogators], and they had promised to close this case within a month at the most,” he wrote.

Noting that being active on social media networks like Facebook and Telegram is not illegal, Saharkhiz wrote that his interrogators had tried to convince him otherwise: “While the Prosecutor General has given an interview on this topic and has not announced a legal barrier for using these networks, the experts [interrogators] considered it illegal and called the Prosecutor General ‘uninformed,’ just as they called many government and state officials ‘amateurs,’ and even ‘traitors.’”

“Such perception and attitude was so prevalent that they even called those working in the government and the president’s colleagues as ‘individuals with issues.’”

Saharkhiz added that although his interrogators described themselves as lawful citizens, they admitted to participating in illegal gatherings “such as the sit-in in front of the Parliament while the nuclear agreement was being approved, the illegal occupation of the British Embassy, and the raid on the Saudi Arabian Embassy, where they were involved directly or indirectly.”

“It must be examined whether these individuals, known as law enforcement agents, have committed ‘assembly and collusion and propaganda against the state,’ causing the emergence of massive negative effects and financial, moral, and international consequences for the state, or people like me, who have had nothing to do with such events!” he wrote.

Saharkhiz previously spent nearly five years in prison for publishing political commentaries critical of the widely disputed results of Iran’s 2009 presidential elections.

Saharkhiz also previously served in President Mohammed Khatami’s reformist administration (1997-2005) as head of the press department at the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance.