Recording on 1988 Prison Massacre Exposes Early Fissure in the Islamic Republic of Iran

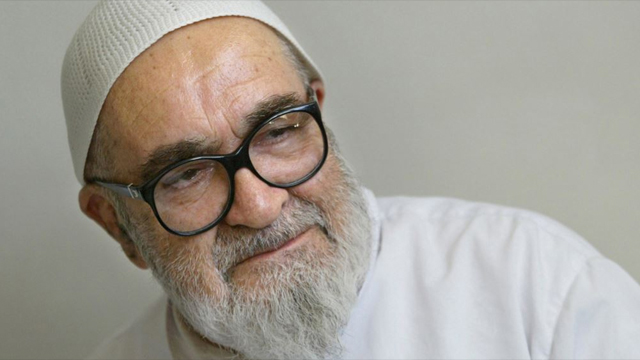

The recently released audio recording of Grand Ayatollah Hosseinali Montazeri sharply denouncing the mass execution of political prisoners in the summer of 1988 has highlighted disagreements among prominent figures of the Islamic Republic that arose from the decision by Ruhollah Khomeini, the leader of Iran’s 1979 revolution, to put thousands of political dissidents to death.

Iranians who were born after the revolution’s turbulent first decade have also taken to social media to call for accountability even though they have no actual memory of the period.

In the audio file posted on Montazeri’s official website by his son on August 9, 2016 (Montazeri died in 2009), the ayatollah described the executions, which were ordered by a special tribunal set up by Khomeini, and which took the lives of an estimated 4,000-5,000 people, as “the greatest crime in the Islamic Republic of Iran.”

Montazeri, who was at the time being primed to become the country’s next supreme leader, told the tribunal—referred to as the “Death Committee” by the victims’ families—that he did not wish for Khomeini to be judged by history as a “bloodthirsty, cruel and brazen figure” for executing political prisoners en masse, and warned the tribunal’s members that they would be remembered as cruel criminals.

The meeting was described sixteen years ago in Montazeri’s memoir, but the recently released audio file has renewed debate on the decision to execute thousands of political dissidents without due process.

According to the announcement published on Montazeri’s website, Judge Hosseinali Nayeri, Tehran Prosecutor Morteza Eshraghi, Deputy Prosecutor General Ebrahim Raeesi and the Intelligence Ministry’s representative in Evin Prison Mostafa Pourmohammadi met with Montazeri on August 15, 1988 to gain his support for the executions. Instead, Montazeri chastised them for killing prisoners without legal justification.

Montazeri also accused Khomeini’s son, Ahmad Agha Khomeini, of instigating the executions: “The Intelligence Ministry promoted the [plan for the mass execution of prisoners] and invested in it, and then three or four years ago Ahmad Agha came along and said the Mojahedin-e-Khalq (MEK—at the time a violent Marxist-Islamist opposition party that bombed the headquarters of Khomeini’s party in 1981) should all be executed, including those who read their newspapers, publications and pamphlets. This was their thinking. After the [MEK] attacked us, [the Intelligence Ministry] thought it was a good time for someone to convince the imam [Khomeini] to agree to [the executions] and got a written order from him to carry them out. I don’t know what this will lead to or what will happen in the future.”

Montazeri’s linking of Ahmad Khomeini (who died in 1995) to the infamous executions has put his son, Hassan Khomeini, on the spot. Hassan Khomeini has publicly aligned himself with prominent centrist and reformist politicians, namely President Hassan Rouhani and former Presidents Ali Akbar Rafsanjani and Mohammad Khatami. The Iranian public has come to see him as a respectable political challenger that could take on hardliners. But the allegation that his father endorsed the executions has implicated Hassan Khomeini in the eyes of the public and threatened to undermine his credibility.

Policy of Persecution

Executions became an intrinsic part of the Islamic Republic’s ongoing policy of political repression and persecution since the early years of the revolution. Under Khomeini’s orders, Revolutionary Courts were quickly set up to punish dozens of officials who served under the toppled Pahlavi Dynasty following the 1979 revolution. Many of them were executed without due process. More than 37 years later, the Revolutionary Courts continue to operate and issue heavy sentences against political prisoners and critics of the regime.

In 1979 the provisional government under then-Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan tried, unsuccessfully, to minimize the role of the Revolutionary Courts with the goal of eventually shutting them down. Jalaleddin Farsi, who was a radical politician at the time, wrote in his memoir that Bazargan told him that he wanted to inscribe verse 8 of chapter 5 of the Quran above the entrance of Revolutionary Courts. The verse tells Muslims “… do not let the hatred of a people prevent you from being just. Be just; that is nearer to righteousness.”

According to Farsi, Bazargan believed that the leaders of the new Islamic Republic, who had themselves been unjustly treated by the Judiciary under the shah’s regime, should break the chain of bitter revenge. “But I told [Bazargan] that the accused [associates of the former regime] are crafty criminals… who have committed countless crimes and acts of treason,” wrote Farsi in his memoir, Zavaayaa-ye Taareek (Dark Aspects, page 480). The ideological current of the first decade of the revolution was against reconciliation and compromise; vengeance prevailed and many were executed after trials that lasted only a few minutes.

In a speech on August 17, 1979, some six months after the revolution, Khomeini criticized himself and the new authorities for being too soft on opponents of the new state: “One of the mistakes we made was that we didn’t act in a revolutionary fashion. We were patient with these corrupt factions. The revolutionary government, the revolutionary army, the revolutionary guards, none of them acted like revolutionaries. We would not have these problems today if in the very beginning we had shattered the former corrupt regime and closed down all these corrupt newspapers and magazines and punished their publishers and banned the corrupt political parties and given their leaders what they deserved and set up gallows in the main squares and cut down all the corrupt people. In the presence of God Almighty and the dear nation of Iran, I apologize for our mistakes.”

But Khomeini’s hard line was resisted by some of his closest aides. In a letter to Khomeini dated September 27, 1981, written during a new wave of executions, Montazeri said: “There are weaknesses within the Supreme Judicial Council as well as the Revolutionary Courts, which, according to sincere and committed individuals who work there, have resulted in deteriorating conditions in Evin Prison and in other prisons where many irregular executions have taken place, sometimes without being sanctioned by a judge. They have even executed 13 and 14-year-old girls, who were unarmed, simply because they spoke harshly. This is very disturbing and frightening. Prisoners are put under increasing pressure and intolerable acts of torture. There are so many prisoners that sometimes five of them are kept in a single cell [meant for] solitary confinement. Sometimes they are not even allowed to perform prayers. According to one of the judges, chaos reigns and the arbitrary actions of the interrogators are very troubling.”

The victims were not exclusively political opponents; members of the Baha’i religious community were also targeted by Iran’s new revolutionary regime. According to a paper written by Michael Karlberg, an associate professor at Western Washington University, “After 1979, following the Islamic revolution led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a renewed wave of persecution engulfed the Baha’i community. Before Ayatollah Khomeini came to power he was already a self-declared adversary of the Baha’i faith and he made it clear that the Baha’i community, which constituted the largest religious minority in Iran with more than 300,000 members, would be denied the basic human rights that would be afforded to other religious minorities in the country. In addition, leaders of the Anti-Baha’i Society assumed many of the most influential positions within the newly declared republic. Therefore, immediately following the revolution, it became clear that the Baha’is were in great danger as, indeed, the Islamic regime began to pursue a program of ‘implacable hostility toward the Baha’is.’ Segments of the population were immediately incited to violence against the Baha’is, who could be attacked with impunity because the new Islamic constitution (echoing the 1906 constitution before it) intentionally denied the Baha’is any legal recognition or civil protections and ‘effectively criminalized the faith’.”

Following the Islamic Republic’s implementation of harsh sharia laws, scores of other groups, namely drug traffickers, homosexuals and adulterers, were also targeted under the theocracy founded on Khomeini’s concept of Velayat-e Faghih (Guardianship of the Islamic Jurist). The ruthlessness that marked the period of Khomeini’s leadership has become a revered model for hardliners who now remind people to appreciate the “benevolent and merciful” leadership of Iran’s current supreme leader, Ali Khamenei.

When Hojatoleslam Mehdi Karroubi, the former presidential candidate who has been under house arrest since 2011 for peacefully contesting the widely disputed result of the 2009 presidential elections, wrote a letter to Rouhani demanding to be formally charged and put on trial, the editorial board of the Revolutionary Guards’ magazine, Javan, replied, “Don’t you want to revive the golden era of the late Imam [Khomeini]? Aren’t you proud you received dozens of titles from his grace? Now the Islamic Republic is taking you back to that era and showing you a small example of how the imam treated those who rebelled against the state… You should pray for Seyyed [Ali Khamenei] for nicely calling you undignified. Back in the golden era, all of you would have been hanged with a short command.”

Khamenei has echoed this line of criticism. In June 2014, when outspoken conservative MP Ali Motahari objected to the house arrests of Karroubi and former presidential candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi and his wife, Zahra Rahnavard, Khamenei replied: “Their crimes are much bigger than their punishment…If the imam [Khomeini] was alive he would have been harsher. If these individuals were put on trial, they would face heavy punishments, which you would not be pleased with. We are being kind to them.”

Mass Executions

The exact number of political prisoners who have been executed in Iran since 1979 is unknown; if any records exist, the government has concealed them. But an investigation by the British Broadcasting Corporation Persian (BBC Persian) from 2013 estimated that—based on interviews with human rights groups and the families of the victims—close to 11,000 people were executed between 1981 and 1985 and more than 4,000 in the summer of 1988.

Montazeri, who was Khomeini’s deputy before being sidelined for opposing the executions, provided some detail about the 1988 prison massacre in his memoir.

“After the MEK, with Iraq’s backing, launched the Mersad Operation against the Islamic Republic of Iran [in July 1988 during the Iran-Iraq war], a number of them were killed and some were taken prisoner. Presumably, they were put on trial. But that is not the issue,” Montazeri wrote. “What prompted me to write a letter at the time was the fact that some individuals had decided to wipe out the MEK and be done with them. They got the imam [Khomeini] to issue an order to deal with their members in prison. A three-member tribunal was formed and if two of the judges decided that such and such prisoner was still adamant on his views, she/he would be executed… The imam’s order does not have a date on it. But it was written on a Thursday and on the following Saturday it was given to me by a judge who was very upset. I studied the order. It had a very angry tone in response to the MEK’s Mersad Operation. It was said that the order was in Ahmad [Khomeini’s] handwriting.” (Montazeri’s Memoir, Vol. 1, page 623.)

Khomeini’s order stated: “Since the treacherous munafiqin [hypocrites, a derogatory term for MEK members] do not believe in Islam, and whatever they say stems from their deception and hypocrisy; and since, according to the claims of their leaders, they have become apostates of Islam; and since they wage war on God and are engaging in classical warfare in the western, northern and southern parts of the country with the collaboration of the Baathist party of Iraq, and are spying for Saddam [Hussein] against our Muslim nation; and since they are tied to world arrogance and have inflicted treacherous blows upon the Islamic Republic since its inception, it follows that those who remain steadfast in their position of hypocrisy in prisons throughout this country are considered as mohareb [waging war on God] and are thus condemned to a sentence of death, and the determination of this issue in Tehran shall be made with a majority decision of Messrs Hojat-ol-Islam, Nayyeri (may his life be prolonged), and his excellency Mr Eshraghi, and a representative of the Ministry of Information. The preference, however, is unanimity. And in the same manner, in the prisons in the center of the provinces, the majority decision of the religious judge, the revolutionary prosecutor or his assistant, and the representative of the ministry of information shall be binding. It is naïve to show mercy to moharebs. The decisiveness of Islam before the enemies of God is among the unquestionable tenets of the Islamic regime. I hope that you satisfy the almighty God with your revolutionary rage and rancor against the enemies of Islam. The gentlemen who are responsible for making the decisions must not hesitate, nor show any doubt or concern with details. They must try to be as ferocious as possible against infidels. To hesitate in the judicial process of revolutionary Islam is to ignore the pure and holy blood of the martyrs.”

According to Montazeri, then-Judiciary Chief Ayatollah Mousavi Ardebili wrote a question on the back of the written order: “Those munafiqs who continue to hold on to their deviant views, and have been sentenced to prison and have served a portion of their sentence, should they be condemned to death as well?” To which Khomeini replied, “In all cases, no matter what their status may be, if they are adamant on their hypocrisy, they should be quickly annihilated as enemies of Islam. As for prosecution, the cases should be handled in a manner that would lead to a verdict as quickly as possible.”

Montazeri added: “Finally, they cancelled prison visitations and based on what I heard from the officials in charge, [Khomeini’s] order resulted in the execution of 2,800 or 3,800 men and women prisoners, but I’m not certain [of the number]. There were even some prisoners who prayed and fasted and were asked to repent and they would be insulted and refuse and then they would be judged for remaining adamant on their views and executed. In Qom, one of the judicial officials came to me and complained about the Intelligence Ministry representative in the city who wanted to quickly kill [MEK prisoners] and get rid of them…” (Vol. 1, page 628).

The Sweden-based Committee for the Defense of Human Rights in Iran has compiled the names of 4,672 prisoners executed in the summer of 1988, but others believe the number is much higher. For example, democracy activist Mohammad Maleki, who was a political prisoner in the 1980s, has said that the actual number could be more than 30,000 because most of the executions took place outside the capital city of Tehran, where they were carried out in secret.

Montazeri also revealed in his memoir that there was a second order issued by Khomeini to execute 500 secular prisoners who were mostly members of the communist Tudeh Party. “The plan was to use this order to get rid of them as well.” The now banned Tudeh Party has published a list naming 100 members who were executed in the summer of 1988.

In June 2012, human rights activists set up a Truth Commission in London to hear testimony from formers prisoners and the families of the victims who were executed in 1988. The commission declared: “These violations of human rights were devised, instigated and executed (or caused to be executed) by a single central authority and as such the Islamic Republic of Iran is the only authority responsible for these acts.”