Judiciary Cites “Lost” Case Files in Denying Man Imprisoned for 23 Years Medical Care

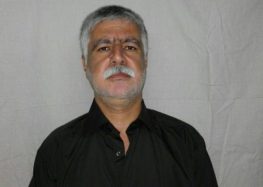

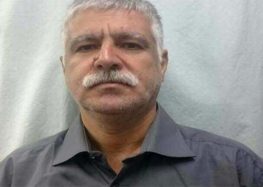

Political prisoner Mohammad Nazari, imprisoned in Tehran for the past 23 years, has told the Campaign for Human Rights in Iran that even though his prison warden sent a letter on his behalf, the Judiciary has denied his urgent request for medical furlough (temporary leave), claiming they have “lost” his case files.

“I have spent more than half my life in prison,” said Nazari, speaking from Rajaee Shahr Prison, in an exclusive interview with the Campaign on January 12, 2017. “That’s not a problem; I don’t want anything from this regime…I’m not asking for freedom…I just want a permit to go to the hospital.”

“Am I doomed to die here like the others?” he added. “What am I supposed to do? We have rights in this country. Where is my file? Is it lost? How can that be? Not even a lunatic could accept this situation.”

“I have cervical disc pain in my neck,” continued Nazari. “A specialist referred me to the hospital last month, but neither [the Revolutionary Court] in Karaj nor the one in Tehran have responded to my requests [for medical leave]. Even the prison warden wrote a letter on my behalf, but unfortunately nothing has been done. Sometimes my hands and legs go completely limp. The prison clinic doctors really don’t know what the problem could be.”

Political prisoners in Iran routinely receive discriminatory treatment, including denial of necessary medical treatment.

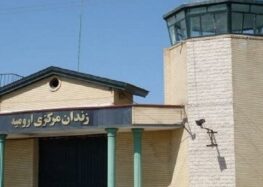

Born on July 11, 1971, Nazari was arrested by agents of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence in the city of Boukan, West Azerbaijan Province, on May 30, 1994. Six months later, Branch One of the Orumiyeh Revolutionary Court presided by Judge Abdolahad Jalilzadeh sentenced him to death for his alleged membership in the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI), an opposition group seeking autonomy for Iran’s Kurdish region.

Nazari’s sentence was reduced to life imprisonment in 1999 amid the Islamic festival of Eid Qorban, when the supreme leader, upon the recommendation of the Judiciary, traditionally pardons some prisoners.

Members of ethnic or religious minorities in Iran who engage in criticism of the government are singled out by the Judiciary for particularly harsh treatment, and there is a well-documented history of the Judiciary disproportionately meting out capital punishment to minority activists.

“I’m stuck. The judicial officials in (the cities of) Karaj, Tehran and Mahabad all say it’s not their problem,” added Nazari. “They say they have lost my files, but maybe they’re screwing with me.”

Pardon Letter or Trap?

“Last year, a representative of the Intelligence Ministry came to prison and we spoke close to an hour,” Nazari told the Campaign. “He said, give us a commitment that you won’t go back to the same (political) activities. I said okay, I’ll make that commitment, but only after I’m freed, not while I’m still in prison.”

He continued: “We have had many cases of prisoners who signed pardon letters and begged forgiveness and are wasting away in prison. It’s true. There are a lot of them and they are dying in prison. I see them and I truly lose hope. I got a lawyer once, but he quit without any explanation. What can I say?”

“Thousands and thousands of PDKI sympathizers walk the streets freely. So why am I in prison? According to the law, being a PDKI sympathizer is not a crime, not even in this country,” he added.

“These people have no idea what life in prison means,” he said. “They’ve never experienced incarceration and yet they issue life sentences by the kilo.”

In August 2002, Nazari sewed his lips shut and went on hunger strike to demand a review of his case, but none of his requests, or those by his family, have been taken into consideration by the Judiciary, he told the Campaign.

“I have no one to follow-up on my case,” he said. “I’ve written a thousand letters to every authority you can imagine, but I haven’t asked for a pardon because I haven’t done anything wrong. I’ve committed no sin. I haven’t robbed anyone or even looked the wrong way at someone’s wife. The only thing that has kept me in prison all these years is the state’s bias towards my beliefs.”