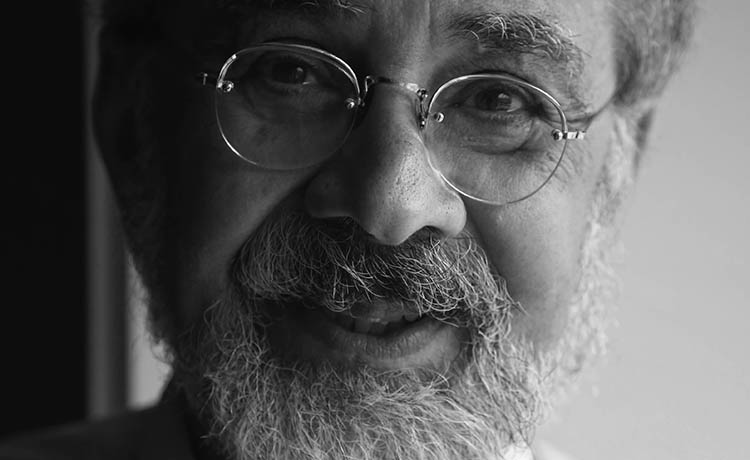

An Interview with Scholar and Historian Ervand Abrahamian on the Islamic Republic’s “Greatest Crime”

- Distinguished professor of Iranian and Middle Eastern history and politics, Dr. Ervand Abrahamian.

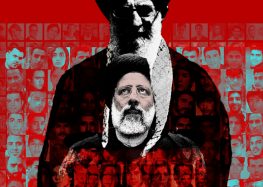

Presidential Hopeful Ebrahim Raisi Served on Committee That Ordered Executions of Thousands

The executions of thousands of political prisoners in Iran in 1988 has received renewed attention due to the presidential election coming up on May 19, in which one of the candidates—Ebrahim Raisi—was a member of the committee that ordered the killings.

The “Death Committee,” as it came to be known, ordered the killings on the basis of two fatwas issued by the Islamic Republic’s founder and then-supreme leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Some were killed after being deemed apostates by the committee.

“This was more of a medieval inquisition, and we have not seen anything like it in modern Iranian history,” prominent scholar and historian Ervand Abrahamian, who chronicled the massacre in his book, Tortured Confessions, told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

At the time, Khomeini’s own heir apparent, Hosseinali Montazeri, bitterly condemned the murders, which seemed intended to end all internal dissent in the then-young Islamic Republic, saying, “…history will condemn us for it…. History will write you down as criminals.”

No Iranian official has ever been held accountable for this crime against humanity. Indeed, Raisi went on to serve in senior judicial positions, and currently heads Astan Quds Razavi, one of Iran’s wealthiest shrine-based religious institutions that effectively functions as a major business conglomerate.

The exact death toll in 1988 remains unknown, because the Iranian government refuses to provide a list of those executed or even acknowledge that the killings took place. Montazeri put the number of executed prisoners between 2,800 and 3,800 in his memoirs. Estimates by human rights organizations, based on lists of names gathered by the United Nations and former political prisoners, state 4,500-5,000 prisoners were killed.

In a 1988 audio recording of a meeting with the committee Raisi served on, the now deceased Montazeri is heard telling the members: “I believe this is the greatest crime committed in the Islamic Republic since the revolution.”

A renowned expert, Dr. Abrahamian has taught modern Iranian history at the universities of Oxford, Columbia, New York, and Princeton, and for over forty years at Baruch College, City University of New York. Excerpts of CHRI’s interview with Dr. Abrahamian follow.

Why did the founder of Iran’s 1979 revolution, Ruhollah Khomeini, order the executions in 1988?

There is much speculation on the reasons for it. One interpretation is that he wanted to empty out the overcrowded prisons, but he could have done that by releasing the prisoners. Another interpretation is that the regime was so insecure, that it saw the executions as a way get rid of the opposition, to improve its security. But that doesn’t make sense either because the regime had basically just concluded the Iran-Iraq War (1980-88) and this was a time of relief, with no upsurge by the opposition.

Since there was no upsurge, we arrive at the interpretation that this was a way for the founder of the Islamic Republic, Ruhollah Khomeini, to really cement who was 100 percent behind the regime. By doing something as outrageous as the horrendous executions, he could divide the half-hearted, from the liberal, to the solid supporters of the regime.

Why did Khomeini decide to appoint Ebrahim Raisi, who will be running for president in May 2017, to the committee?

Khomeini issued two fatwas (Islamic decrees) for the creation of the committees, and clearly he wanted the executions, so he appointed hardliners. He must have thought Raisi was a good person for that.

Raisi was very young at the time, and not very prominent. Only after he was appointed to head Astan Quds Razavi did people remember his role in the executions.

The only person of the four (then-Judge Hosseinali Nayeri, then-Tehran Prosecutor Morteza Eshraghi, then-Deputy Prosecutor General Ebrahim Raisi and the Intelligence Ministry’s representative in Evin Prison at the time, Mostafa Pourmohammadi) who was less hardline and tried to bend the rules to save some people, was Eshraghi. But the others were all hardliners.

Can you elaborate on the fatwas issued by Khomeini?

There is one thing that people don’t realize. There were two fatwas, one was directly aimed at the Mojahedin-e Khalgh (MEK), [an opposition group dedicated to the overthrow of the regime] the other was directed towards non-Mojahedin prisoners. Now, the fatwa for the Mojahedin was designed to see who was still sympathetic enough to the MEK that, even if they disassociated themselves from it, they were not willing to go against it and fight it. This was a fatwa against “warring against God.” These were political executions, which is not abnormal for a revolutionary regime.

The second fatwa was more sinister and more significant. Very few people have mentioned it, and even Montazeri doesn’t mention it in his denunciation of the executions. This was basically a fatwa against apostasy, on whether you were born a Muslim, but no longer believe in Islam. So this was no longer a political issue. This became about prisoners’ belief in God.

This time the committee wasn’t asking questions like, “Do you support the regime? Are you against the regime?” Because most of the prisoners were actually supportive of the regime. Now they were asking things like: “Do you pray? Do you believe in the afterlife? Do you believe in the Koran is the word of God?”

This was more of a medieval inquisition, and we have not seen anything like it in modern Iranian history.

And these prisoners, if they gave the wrong answer, for example, if they said, well this is a personal belief and I don’t have to answer, or were raised as a Muslim and no longer believe, that would be proof of guilt. Then they were an apostate, and being an apostate according to the regime’s interpretation of sharia (Islamic law), meant you could be executed. So this is a very different type of trial than a political trial. This is like a trial in medieval Europe on heresy.

The executions for apostasy had not happened before?

The execution of people for apostasy is a novelty. It hasn’t ever happened in Iran. In the past people have been executed for misinterpreting Islam, but I don’t know of anyone being executed for not believing in the afterlife.

There is another interesting thing about the Montazeri revelations. In there, he figures out that (current Supreme Leader) Ali Khamenei, who was at the time president, was not even aware of the second fatwa. So it was really just known about by Khomeini, his son Ahmad, and those who were directly involved in the executions.

Montazeri sent his protest to Khamenei as president, trying to get Khamenei to do something about it and didn’t succeed. Then, in the discussions, he discovers that Khamenei didn’t even know about the second fatwa.

Were the executions legal?

According to the law, you must have been found guilty of something that would warrant execution, such as armed struggle against the regime. But the people who were executed in the mass executions had not been accused of that, and had been serving sentences for much lesser crimes. They had already been tried and not found guilty of capital offenses before, and then they were suddenly brought back and executed.

How involved was Khomeini in the process?

As with many of Khomeini’s decisions, he wasn’t directly involved. He issued the fatwa for the committees to carry out the retrials of the people, and appointed the judges, so then he wasn’t made responsible for deciding who was executed.

Did the government document the killings?

They tried to hide everything and were completely secretive about it. If anyone did raise questions at the time, the government just denied it happened. Of course, the information did eventually get out because they killed so many family members.

What were the main prisons that the executions took place?

The vast majority were killed in Tehran, primarily at Gohar Dasht Prison, and the majority of those executions were done under the first fatwa. The list I found said about 300 were killed under the second fatwa.

In Tehran, the sentencing was carried out by a special committee appointed by Khomeini. Later the families of the victims would call it the “Death Committee” Local judges would have been appointed to do the task in the provinces. This all took place in the course of about three months.

How were the families informed?

The ones who were killed for apostasy were not placed in the official cemeteries. They were dumped near the desert towards Khorasan Province. It was again through word of mouth that family members discovered the graves.

Some of the bodies were not properly buried, so parts of the bodies would reappear in the desert land and formerly the families would gather there and take flowers.

The other families (killed under the first fatwa) often got some of their last testaments. There was a tradition that prisoners who were to be executed could write their will and it would be sent to the family. Again, the regime is very bureaucratic, so if they had eyeglasses or clothes, those would be returned to the family. But usually it took a while. The government stretched it out so it would be months before all the family members knew what had happened.

After the 1980s, did Iran see any more mass executions of this type and this scale?

No, since then there hasn’t been a real opposition. After the executions, those who were not executed were released en mass. So if you survived the inquisitions or the Mojahedin trials, within months of the executions the prisons were emptied out.

But a lot of the people who were then released were so fearful that this could happen again, that many of them basically just left the country.

The regime was already successful at defeating the opposition before that. The Mojahedin had really been defeated long before and their last bid for power was when they came across the border to invade Iran [in the Iran-Iraq war] and they were militarily defeated in 1988.