Iran’s Expediency Council to Decide Whether Religious Minorities Can Run in Elections

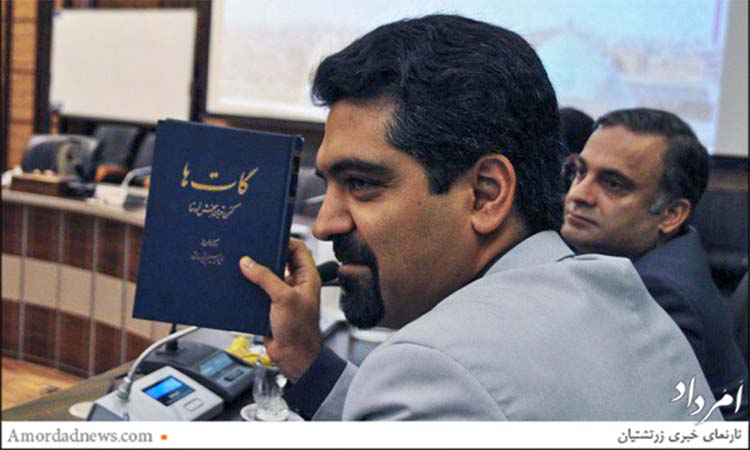

Yazd city councilman Sepanta Niknam holds up a book called Ghathas, the 17 Avestan hymns of the Zoroastrian religion, during a council meeting.

An ongoing dispute in Iran over whether religious minorities can be elected to local councils in Muslim-majority constituencies could be decided by the country’s highest arbitration body, the Expediency Council.

This issue became public after the head councilman of the city of Yazd, in southeastern Iran, refused to carry out a court order suspending the membership of a fellow councilman who is a member of the minority Zoroastrian faith.

“You cannot do everything you like in the name of religion,” said Mohammad Taghi Fazel Meybodi, a member of the Assembly of the Qom Seminary Scholars and Researchers, in an interview with the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) on October 17. “The people’s votes are sacred.”

“Taking away the votes that the people cast for Mr. Niknam would violate his rights and leave a bad precedent in the name of Islam,” said Meybodi, a professor of theology at Mofid University in the holy city south of Tehran.

“The people have put their trust in a Zoroastrian to be their representative in the city council. No one can say they can’t do that,” he added. “This would be against Islam. People’s rights should be respected. They voted for Mr. Niknam. That’s the meaning of democracy.”

On October 18, 2017, Parliament Speaker Ali Larijani restated that removing Sepanta Niknam from his elected seat because he isn’t Muslim is illegal.

“If this matter is not resolved, we have no choice but to refer it to the Expediency Discernment Council for a final resolution,” said Larijani in a meeting with a group of city councilors.

According to Article 112 of Iran’s Constitution, the Expediency Discernment Council can issue final rulings when the Guardian Council, the clerical body that vets elections and laws for conformity with Islamic principles, and Parliament cannot agree on a piece of legislation.

“In my talks with Ayatollah [Ahmad] Jannati, the honorable secretary of the Guardian Council, I emphasized that local councils should be handled according to the law,” said Larijani.

A month before Iran’s local council elections in May 2017, Jannati issued a ruling on behalf of the Guardian Council declaring the Law on the Formation, Duties, and Election of National Islamic Councils to be against Islam.

Article 26 of the law permits followers of all the religions recognized in Articles 12 and 13 of the Constitution—Islam, Judaism, Christianity and Zoroastrianism—to run as candidates in elections.

The possibility of the Expediency Discernment Council getting involved became stronger after Guardian Council Spokesman Abbasali Kadkhodaei announced that the implementation of Jannati’s ruling was mandatory.

“In the opinion of the Guardian Council, religious minorities cannot become members of local councils in areas where the majority are Muslims,” said Kadkhodaei. “Legislators who have protested Mr. Niknam’s suspension don’t understand the law.”

After the election on May 19, Ali Asghar Bagheri, a Muslim candidate who did not win a seat in Yazd’s city council, filed a complaint with Branch 45 of the Administrative Court. In August 2017, the court ordered Niknam’s “temporary suspension,” even though he was elected with a higher vote than in the 2013 elections.

Niknam, a 32-year-old economist who leads Yazd’s Zoroastrian Association, mentioned his faith during both his campaigns.

Yazd is home to some of the world’s most revered Zoroastrian religious sites. Followers of the ancient pre-Islamic faith have lived in the region for thousands of years. Their population in Iran had dwindled to about 25,000 as of 2011, according to a national census.