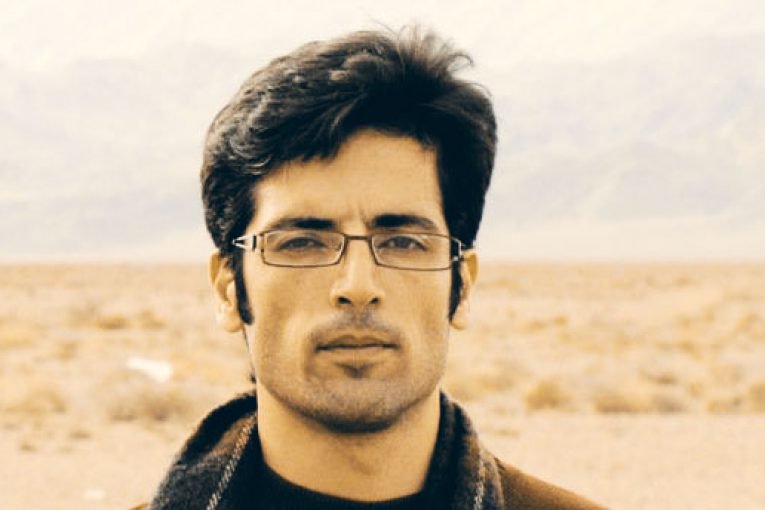

Political Prisoner Majid Assadi Denied Hospitalization in Rajaee Shahr Prison

Political prisoner Majid Assadi is being denied urgent hospitalization despite severe pain in his spine and digestive problems, the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) has learned.

Political prisoner Majid Assadi is being denied urgent hospitalization despite severe pain in his spine and digestive problems, the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) has learned.

“The doctor ordered my son to get a sonograph a month ago to find out what new medications he needs but the authorities are giving us the run around from this office to that while he’s getting worse every day,” Assadi’s mother, Fatemeh Vakili, told CHRI on December 28, 2017.

A source close to the family who requested anonymity for security reasons told CHRI that Assadi’s spinal disk inflammation has worsened in recent weeks, causing severe side effects in his digestive tract.

“His doctor says if he doesn’t get treatment, he could face irreversible problems,” added the source.

Political prisoners in Iran are singled out for harsh treatment, which often includes denial of medical care.

Assadi, 35, has been behind bars in Rajaee Shahr Prison in Karaj, west of Tehran, since his arrest by Intelligence Ministry agents on February 18, 2017. On November 27, Branch 26 of the Tehran Revolutionary Court sentenced him to six years in prison and two years in exile in Borazjan, Bushehr Province for “propaganda against the state” and “assembly and collusion against national security.”

“They have condemned my son to six years in prison and two years in exile without any evidence,” said Vakili. “The whole family is worried and upset. If he wasn’t so sick we wouldn’t worry as much, but he’s suffering.”

A translator at a private company, Assadi was previously sentenced to four years in prison in March 2010 for “assembly and collusion against national security” by Branch 15 of the Revolutionary Court. He completed the sentence on June 8, 2015.

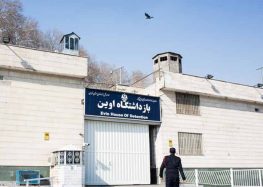

Known for its harsh living conditions, Rajaee Shahr Prison, also called Gohardasht, holds more than 50 political prisoners and prisoners of conscience.

In December 2016, political prisoner Saeed Shirzad sewed his lips shut to hunger strike against what he described in a letter sent to judicial officials as “the quiet death of prisoners,” a reference to human rights violations suffered by prisoners at Rajaee Shahr Prison.

A prominent human rights lawyer who was incarcerated in Rajaee Shahr Prison told CHRI in April 2016 that “the prison was not in any condition to hold that many prisoners.”

“The clinic did not have medicines to treat anything worse than a cold, let alone high blood pressure,” said Mohammad Seifzadeh. “Bad nutrition and lack of vitamins weakened the prisoners.”

“Fruits and vegetables are non-existent,” he added. “Some of us prepared our own food. We gave a list of things we needed and they would buy it for us from outside at our own expense. But there were also those who only ate prison food. Two days a week there was stew and on other days it was only rice and soybean oil, which was greasy and unhealthy.”

“The cells had no ventilation,” said Seifzadeh. “In Evin Prison, the cell doors opened at a quarter to seven in the morning and you could take in fresh air until sunset, but in Rajaee Shahr we could only stay outside for three hours.”