Iran Poised to Block Popular Telegram Messaging App But Lacks Feasible Alternative

- Decision made at the “highest level” has set the stage for blocking social network used by 40 million.

- App can be blocked on supreme leader’s order but Iranians unlikely to flock to domestic alternatives due to privacy concerns.

After months of unsuccessful attempts by Iranian officials to convince the Telegram encrypted messaging app to comply with domestic censorship policies, Iranian officials are now openly discussing blocking the widely used social media network.

According to the chairman of the Parliamentary Committee for National Security Affairs and Foreign Policy, the decision to do so has been made at the “highest level,” but for now, the app is still accessible in Iran.

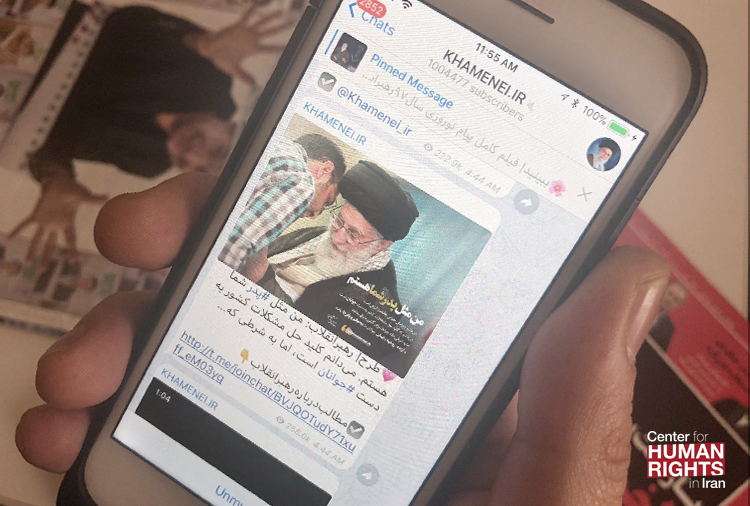

For years, the authorities have been encouraging domestic companies to create their own versions of Telegram, which has reported that it has 40 million users in Iran. Telegram has refused requests by Iranian officials to move its servers to the Islamic Republic, which would make Iranian users’ personal data and communications vulnerable to spying by state agencies.

The state’s widespread monitoring of personal communications in Iran has resulted in severe lack of trust among the public about apps that have been developed in Iran with state approval and/or financial assistance.

Some officials have publicly acknowledged that Iranians are extremely suspicious of state-approved domestic apps.

During the course of the recent protests that occurred in dozens of cities across Iran beginning in December 2017, the authorities blocked Telegram for two weeks. But instead of flocking to domestic messaging apps, “30 million” people used circumvention tools—such as virtual private networks (VPNs) that enable users to access blocked sites—to use Telegram according to Member of Parliament (MP) Mahmoud Sadeghi.

The reformist politician tweeted that the number was quoted in a report by the telecommunications minister to the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC). Sadeghi added that a fellow MP also said that day that “people are not enthusiastic about domestic messaging services because they don’t trust that their private information will be secure.”

The internet is heavily censored and monitored in Iran, with millions of websites blocked along with widely used American-owned apps such as Facebook and Twitter. But until now, Telegram, which is based in Dubai and owned by Russian CEO Pavel Durov, had survived attempts by conservative officials to get it banned.

Previously, conservative officials had cited security and privacy issues as reasons why Telegram should be blocked. Now the company’s decision to offer “cryptocurrency”—digital currency that would enable commerce and transactions to occur within the app—is being cited as a reason why the app should be blocked.

Conservative officials claim that this will disrupt and harm the country’s economy.

Some government officials, such as President Hassan Rouhani, have expressed support for the compromise notion of domestic messaging apps functioning alongside foreign ones including Telegram.

But conservative officials argue that Telegram is engaging in unfair competition by monopolizing Iranian cyberspace and leaving no room for domestic competitors.

To maintain the state’s ability to easily monitor and censor online content in Iran, conservative officials have been encouraging the growth of domestic apps while working to eliminate citizens’ access to foreign-made ones.

“Decision Made at the Highest Level”

With the exceptions of the enduring ban imposed on its voice service in 2017 and being blocked for two weeks during the country’s recent December/January protests, Telegram has been freely accessible in Iran since its launch there in 2015.

Unlike Facebook and Twitter, the app had remained accessible in Iran mainly because President Rouhani had resisted pressure to block it. He and his allies had greatly benefited from using Telegram’s “channel” feature to rally support among the electorate during presidential and parliamentary campaigns.

But for years conservative officials have been citing reasons why Telegram should be blocked, with hardliners recently complaining that the app was used to encourage rioting during the country’s recent protests and that it enables foreign powers to foment dissent.

“The SNSC decided to filter Telegram because some people used it to take advantage of the circumstances in the country and create a climate of violence and chaos,” said Ramazanali Sobhanifard, a member of the Taskforce to Determine Instances of Criminal Content, the body responsible for blocking and unblocking online content in Iran, on January 6, 2018.

On January 13, Gholamreza Jalali, the head of the Ministry of the Interior’s Passive Defense Organization, said, “The big data in social media networks isn’t important to us at all but it is used by them to get a clear and penetrating image of our society and it lets them see where the explosive points are.”

“We have given this big data gathered from 40 million people to the enemy and as a result, the enemy has a greater intelligence reach than our own intelligence agencies,” he added.

Telegram has repeatedly refused requests by Iranian officials to transfer its servers to Iran or comply with officials’ requests to censor content that doesn’t violate the company’s communications rules.

This is one reason why Iranian citizens use Telegram’s encrypted messaging service, because they believe their personal data is safer on servers based outside the country.

Rather than working to build trust in domestic apps among the Iranian public, hardline officials have responded to this trend by trying to eliminate foreign ones.

“Based on reliable information I’ve received from the Telecommunications Ministry, the permanent filtering [blocking] of Telegram has been approved by the Supreme Cyber Council,” said Hamideh Zarabadi, a reformist member of the Parliamentary Committee on Industry, on March 17. “Such comments are meant to prepare the public for the implementation of this decision.”

Statements by Alaeddin Boroujerdi, the chairman of the Parliamentary Committee for National Security Affairs and Foreign Policy, also indicate that Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has given his blessing, thus opening the floodgates to coordinated and widespread attacks on the app.

Referring to the recent protests and their impact on decisions regarding Telegram Boroujerdi said, “Despite talks between the government and Telegram’s CEO regarding filtering channels that have encouraged actions against security, Telegram’s officials have not been cooperative with Iran.”

“Telegram will be replaced by a similar national one and this is a decision that has been made at the highest level,” he added.

Rampant Distrust of Domestic Apps

As the country’s most powerful decision-maker, the supreme leader can order a nationwide ban on Telegram, but he can’t force people to use domestic versions.

Messaging apps developed in Iran have been available for months but have been unable to attract a substantial number of subscribers for various reasons, including the public’s lack of trust in apps that store their data on servers in Iran, leaving it open to security agencies.

Some Iranian officials have acknowledged this problem.

“The people are disinclined and distrustful of domestic apps in the same way they distrust the state broadcasting organization,” said Abdolreza Hashemzaei, a member of the Parliamentary Committee for Councils and Domestic Affairs, on January 10. “This lack of trust has impacted all aspects of mass communication.”

Telecommunications Minister Mohammad Javad Azari Jahromi also acknowledged this distrust on January 14, “Unfortunately, because of poisonous propaganda, the people don’t have complete confidence and trust in domestic apps and they think that their privacy will be violated or that they will face some problems.”

On March 19, MP Parvaneh Salahshouri rejected the notion that people are wary of domestic apps due to “propaganda.”

“Domestic messengers don’t have technical or infrastructure problems,” she said. “The problem is the people’s lack of trust, which the Telecommunications Minister cannot fix.”

“People like Telegram not because domestic messengers have technical issues but because they don’t trust them,” added Salashouri.

In a tweet on March 31, MP Farid Mousavi urged against blocking Telegram, arguing that doing so would only increase distrust among the public.

“Just as closing some newspapers has not increased people’s interest in other newspapers, and just as banning satellite dishes has led to its greater popularity, filtering Telegram will also fail to attract public interest in messengers they don’t trust,” he said.

“Let’s learn from our past failed experiences,” added Mousavi.

Following the news that Telegram could soon be permanently blocked, Iranians have taken to social media to reject hardline officials’ justifications for the decision and express their unwillingness to use domestic messaging apps.

Iranian user Captain Hadook tweeted on April 3, “True trust can develop when by ‘choice’ you use a domestic messenger over a foreign one, not by ‘force.’”

“I would rather let foreign intelligence services have access to my most private information than use domestic messengers,” tweeted Iranian user Majid on April 1.

“You killed a university professor [Kavous Seyed-Emami] in prison and before his shroud was dry, you made a documentary based on his personal family photos and proudly aired it on TV,” he added. “You guys are really disgraceful.”

Former Iranian political prisoner Hossein Nouraninejad tweeted on April 2: “In 2009 my Yahoo email account was hacked and they pressed unbelievable charges against me based on what they had found. For instance they said I had received political emails! When they hacked my Skype account in 2014, I was charged with having journalists in my contacts. If I use domestic messengers I would probably be a masochist.”

Political activist Maryam Abdi tweeted on March 17, “Personally I would send messages by smoke signals, the pony express or pigeons before I ever touch domestic messengers.”

From Security Threat to Private Sector Enemy

In addition to their frustration over their inability to monitor and censor data on Telegram, conservative officials have lately opened a new front against Telegram’s new digital cryptocurrency, which would allow users to send and receive money.

In a television interview on April 3, Abolhassan Firouzabadi, the secretary of the Supreme Cyberspace Council (SCC), the highest internet decision-making body in Iran set up by the supreme leader, said the cryptocurrency would harm Iran’s economy.

“Telegram wants to turn our country into an insurance company or a real estate agency and such, and to carry out independent transactions regardless of their legal or illegal nature, without checking to see if they meet necessary standards, without any oversight,” he said.

“If we allow Telegram to enter our economy in this fashion, dozens of companies will be wiped out in the country and millions will lose their jobs, he added. “Therefore, we have reached a conclusion in the council that we need domestic messengers with multiple and financial platforms.”

Firouzabadi continued: “Telegram will put millions out of work. They are highway robbers. Our issue is with Telegram’s financial services because it’s turning into a pyramid scheme that will create problems for our economy. Telegram is seeking to turn the Iranian economy into an intermediary company and that will destroy jobs such as in real estate and auto trading.”

Firouzabadi also accused the company of refusing to work with Iran’s private sector.

“Even though Telegram has facilitated the expansion of internet usage and the development of some businesses in cyberspace, the network has never agreed to cooperate with our private sector,” he said. “Despite its claims, Telegram is an adversary of our private sector.”

“It could have had a profitable relationship with our private sector but it has preferred to operate outside our border and promote its digital currency,” he added. “We cannot be indifferent to this.”

“Telegram has raised two billion dollars in initial coin offering from American investors,” he said. “But it has the most users in Iran and enjoys a monopoly and makes most of its money here and yet it has not invited Iran’s private sector to participate.”

Firouzabadi failed to mention that even if Iranian investors wanted to participate, they would have been prevented from doing so due to international economic sanctions that block or hinder Iran’s access to the global market.

That same day, the country’s largest state-funded television and radio broadcaster, Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting (IRIB), featured guests who echoed Firouzabadi’s attacks.

On a news show, Mohammad Reza Fallah, who was introduced by IRIB as a university academic, claimed that Telegram could “devalue the national currency,” which would cause serious damage to Iran’s economy.

In response, Shahram Sharif, an Iranian internet freedom activist, tweeted, “Neither he nor the presenter pointed to the fact that their argument is irrelevant since Telegram has officially announced that Iranians cannot use its digital currency because of sanctions.”

These attacks on Telegram come on the heels of the supreme leader’s declaration of the New Year, which begins on March 21 in Iran, as “The year of support for domestic producers.”

Coupled with President Rouhani’s focus on improving the economy, these issues have strengthened conservatives’ arguments against Telegram and emboldened their longstanding resolve to block the app in favor of domestic versions.

No Iranian official has presented evidence explaining how Telegram could harm Iran’s economy. But the argument for banning the widely used app has now shifted from Telegram posing a security threat to Iran to Telegram posing both security and economic threats.

From Security Threat to Unfair Competition

In a meeting with economic officials on January 8, 2018, during the two-week ban on Telegram amid the nationwide protests, President Rouhani did not mention the app by name but said the block on “one of the social media networks” had caused 100,000 Iranians to lose their jobs.

“One of these networks was shut down for a few days because of the security situation in the country and now some want to take advantage of this,” he added, referring to conservative politicians who oppose freedom of expression on social media.

“You think it was very good to shut the down the network? You slept well but should it stay shut down forever?” he said. “While you were having a good sleep, 40 million people were in distress.”

“You think only about yourself, added Rouhani. “Meanwhile, 100,000 people have lost their jobs in this past week. Your job situation may have improved but we have to be mindful of the people’s demands and livelihood.”

Some of Rouhani’s supporters, such as Tehran MP Mahmoud Sadeghi, interpreted his comments as a sign of his strength in “overcoming external pressures.”

Based on what can be discerned from his speeches, the president now appears to be in favor of encouraging the growth of domestic messaging apps while allowing people to use foreign ones.

“The existence of powerful, secure and inexpensive Iranian messengers will undoubtedly be a source of pride to all,” said Rouhani during an April 3 meeting with a number of his cabinet ministers, provincial governors and other senior government officials.

“The purpose behind creating and strengthening these domestic apps should not be to filter or block others,” he added. “Rather, the goal should be to end the monopoly on messaging apps.”

Rouhani’s mention of an alleged “monopoly” on social media apps in Iran has long been part of the conservative’s arguments against Telegram.

But Telegram acquired its substantial user base in Iran’s free competition market alongside other foreign and domestic apps.

Being based abroad, Telegram did not benefit from financial arrangements with Iranian officials and has not pulled any political, security or economic strings to eliminate its rivals.

Some officials have also admitted that Telegram’s success is not due to its superior capabilities but because people don’t trust domestic apps.

Taken together, these statements clarify the real reason why Iranian apps can’t compete with Telegram. The issue is not a so-called monopoly by Telegram, but distrust among the user base.

The Iranian state policy of attempting to control and monitor all personal communications and data in the country has resulted in strong suspicions among the public over domestic apps approved of by the state as well as state officials’ reasons for trying to shut down foreign ones.

Many domestic developers have established close ties with state agencies and the country’s security establishment—such as the Intelligence Ministry and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps—and are benefiting financially from these relationships.

The fact that domestic app developers receive substantial government support, which would not be provided if state agencies were not able to access the data stored on their servers, is not lost on the Iranian public.

Some officials have publicly acknowledged this issue.

“Companies that are supposed to develop messengers to replace Telegram are attached to certain agencies,” said MP Hamideh Zarabadi on March 17.

“The facilities needed to launch the alternate networks are exclusively in the hands of two companies tied to the state,” she added. “Under these circumstances, users will not trust domestic messengers.”

The intensification of attacks on Telegram by hardline Iranian officials during the past week—including their attempts to blame the social network for some of the country’s security and economic problems—coupled with their propping up of Iranian-made apps, indicates that Iran is not only making its way towards permanently blocking Telegram. It’s also trying to create a monopoly for domestic apps that will prevent foreign apps from entering the market.

It’s unclear whether the state will be able to overcome the public’s distrust of domestic apps. But these efforts are a strong indication of the extent hardline officials will go to restrict internet freedom and expand censorship policies under various guises.