Shirin Ebadi: Iran’s Judiciary is a “Branch of the Intelligence Ministry”

Nobel Peace Laureate Shirin Ebadi was Iran’s first female judge before being forced to resign in the aftermath of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, when females were barred from being judges. In 2002, she founded the Defenders of Human Rights Center as one of the country’s top human rights lawyers, only to be forced into exile in 2009.

In a phone interview with the Center for Human Rights in Iran, Ebadi, who is now based in London, spoke of the “corruption” that pervades Iran’s judiciary. “I must emphasize that under [former Chief Justice] Sadegh Larijani, the judiciary lost its independence and became a branch of the Intelligence Ministry,” she told CHRI on March 28, 2019. “The judges have agreed to issue verdicts based on whatever is dictated by security agents.” Excerpts of the interview follow.

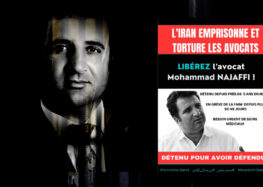

CHRI: In recent years, Iran’s judiciary has brought a variety of charges against prisoners of conscience, in effect criminalizing their peaceful actions. For instance, attorney Mohammad Najafi is currently in prison on eight charges. Nasrin Sotoudeh has been slapped with seven charges. And then there are the Gonabadi dervishes, who were also imprisoned for activities that are non-violent in nature. These “national security” charges are presented in court and result in stiff prison sentences without any credible evidence. What is your legal perspective on this judicial process?

Ebadi: These actions cannot be legally justified in any way. They violate not only international laws but also Iran’s own domestic laws ratified by the Islamic Republic. The actions individuals are being accused of in court are not crimes according to Iran’s own laws. For example, Narges Mohammadi has been sentenced to 16 years in prison, 10 years of which will be enforced. Or Nasrin Sotoudeh has been sentenced to 33 years in prison, 12 years of which will be enforced on charges that include being a founder and ongoing member of the Defenders of Human Rights Center. Which law says that’s a crime? The law says the opposite. The Constitution states that people are free to form groups and create civil and political organizations as long as they do not oppose Islam [Article 26].

Therefore, there are people, such as these two women, who are in prison for things that are essentially not crimes. Defending those accused of political crimes or prisoners of conscience does not mean you are on their side or somehow collaborating with them. If a lawyer defends a murderer in court, does that make him/her an accomplice to murder? If a defense lawyer has a client who believes in overthrowing the regime, that does not mean he/she shares the client’s views.

If we look at every single charge brought against civil rights activists, especially human rights advocates, we see that under our laws, none of them are crimes. Opposing capital punishment is not a crime. Nowhere is it a crime for someone to express opposition against a certain law.

CHRI: Given the points you mentioned, how could the judiciary’s actions be legally justified?

Ebadi: We can easily summarize the actions of the judicial branch during the past 10 years when Sadegh Larijani was at its helm [as chief justice]: It consistently disregarded the law. It has disregarded international laws and commitments undertaken by the Iranian government as well as the laws passed by Parliament.

I must emphasize that under Sadegh Larijani, the judiciary lost its independence and became a branch of the Intelligence Ministry. The judges have agreed to issue verdicts based on whatever is dictated by security agents.

I had many clients who had been threatened by their interrogator that if they did not admit guilt, they would be sentenced to 10 years in prison. Then when we would go to court, that same interrogator would be present monitoring the proceedings and the judge would issue a prison sentence of exactly 10 years. I witnessed this many times. Moreover, there’s a lot of administrative corruption and bribery in non-political judicial proceedings as well. For those reasons, when I was still working in Iran, I would tell people that they should avoid going to the judiciary because they could not expect to see justice in this system.

The worst part of this corrupt judicial system has been its interference in the bar associations. By law, anyone who wants to become a candidate for a seat on the board of directors of the bar association must be approved by the Disciplinary Court for Judges—in other words, by the corrupt judicial system itself. Lawyers have to vote from among handpicked candidates and as a result, corruption has penetrated all levels of the legal and judicial system.

CHRI: Given these unjust and unlawful circumstances, how could the judiciary be made accountable? What role could international organizations play?

Ebadi: There are no solutions that can fix the existing system because Iran’s political structure and Constitution would not allow it. The judiciary chief is directly appointed by the supreme leader and chosen every five years from among qualified Shia jurisprudence and he has complete authority and responsibility over all its actions and appointments. He only answers to the supreme leader, not to Parliament. If someone files a suit against a judge, the case goes to the Disciplinary Court for Judges, which is itself part of the judicial system under the control of the judiciary chief who sits on top of it as an appointee of the supreme leader.

When he was the Tehran prosecutor, Saeed Mortazavi was sued many times especially after the Kahrizak affair in 2009 [when political prisoners died as a result of torture], but did any of those cases go anywhere? Has he really gone to prison? Are you confident he was in prison for the short period he was supposed to be behind bars? They lied to the people about him to calm public opinion. When he took part in the march to Karbala [a pilgrimage to the tomb of Imam Hossein in Iraq], he was supposed to be in prison. What sort of prisoner was he? These are all a mockery of justice. So I must honestly say that I do not see any solution coming out of this political structure and Constitution.

CHRI: Lawyers and families of many prisoners have been saying that recent trials have been held without the presence of legal counsel and lasted just a few minutes. The judiciary has in effect eliminated the right to defense. What role can the bar association play in confronting the judiciary in this regard?

Ebadi: In response to the previous question, I mentioned how the judiciary has infiltrated the legal profession. When the bar association was reopened in 1992, a law was passed that candidates for seats on the board of directors must be approved by the Disciplinary Court for Judges and since then, members of the board of the bar association have always been confirmed by the judiciary and the Intelligence Ministry.

The bar association has not come to the defense of any of the detained lawyers. It did nothing for Abdolfattah Soltani, who spent eight years in prison for defending political prisoners. Or for Mohammad Seifzadeh, who was in prison for six years. Or for Nasrin Sotoudeh and Mohammad Najafi who are now in prison. In truth, the bar association’s board of directors is supposed to speak for the legal profession but has done nothing to support these lawyers.

Since June 2009, about 60 lawyers have been prosecuted in Iran. Some have endured prison and some are still in prison. Others have been forced to leave the country to avoid prison. How has the bar association defended its members in all these cases? Not only did they fail to defend them, they also acted in harmony with the judiciary against their colleagues.

When attorney Shadi Sadr was being prosecuted, the bar association was one of the plaintiffs. They held a disciplinary hearing and brought her in handcuffs and her picture was published everywhere and not one member of the bar association came over to tell the prison guards to remove the handcuffs out of respect for the bar association.

These state-approved bar association board members are speaking on behalf of Iranian lawyers in international forums and have lucrative contracts with private companies. It’s obvious that to them, seeing another lawyer in handcuffs is not important, nor is it important when their colleague is sentenced to 10 years in prison. It’s mired in corruption. It’s going in the same direction as the judicial branch.

CHRI: Many political prisoners and prisoners of conscience have been convicted of repetitive charges. For instance, Nasrin Sotoudeh has been twice convicted of membership in the Legam organization, which peacefully advocated against capital punishment. Do these serial convictions have any legal justification?

Ebadi: These charges and convictions are unjustifiable under the Islamic Republic’s own laws. You mentioned Ms. Sotoudeh’s case in regards to Legam and I would add the fact that she and Ms. Mohammadi have been twice charged with membership in the Defenders of Human Rights Center for which Ms. Mohammadi once served six years in prison for and now she has been sentenced to 16 years in prison. Ms. Sotoudeh once served three years in prison for membership in the Defenders of Human Rights Center and Legam and now she has again been charged with membership in Legam and the Defenders of Human Rights Center.

In Iran, the law says that you can be prosecuted for a crime one time. But Narges and Nasrin have been prosecuted twice for the same charges that are not crimes in the first place. Opposing executions is not a crime, neither is membership in a human rights organization. But the judicial branch has no respect for the law and has no intention of enforcing it. Instead, it takes orders from the Intelligence Ministry. The only explanation for this is that politics have entered the judiciary.

CHRI: One of the things families of prisoners and their lawyers have been complaining about is that the courts are not giving them copies of their verdicts. Their lawyers are only allowed to take handwritten notes off the original verdicts. What are the legal implications?

Ebadi: This is another unlawful action by the Revolutionary Courts. The law says that defense attorneys or their clients should get a copy of the verdicts but the courts are only letting attorneys read the case files and take notes.

The judges know their verdicts are unlawful and don’t want to hand over proof of that to anyone. They think they can hide behind tall walls of secrecy. When so many young prisoners were executed in the 1980s, they were not handed verdicts. None of the families saw the verdicts. That’s why the Iranian government thinks it can deny these crimes in international forums, because no copies of the verdicts were issued.