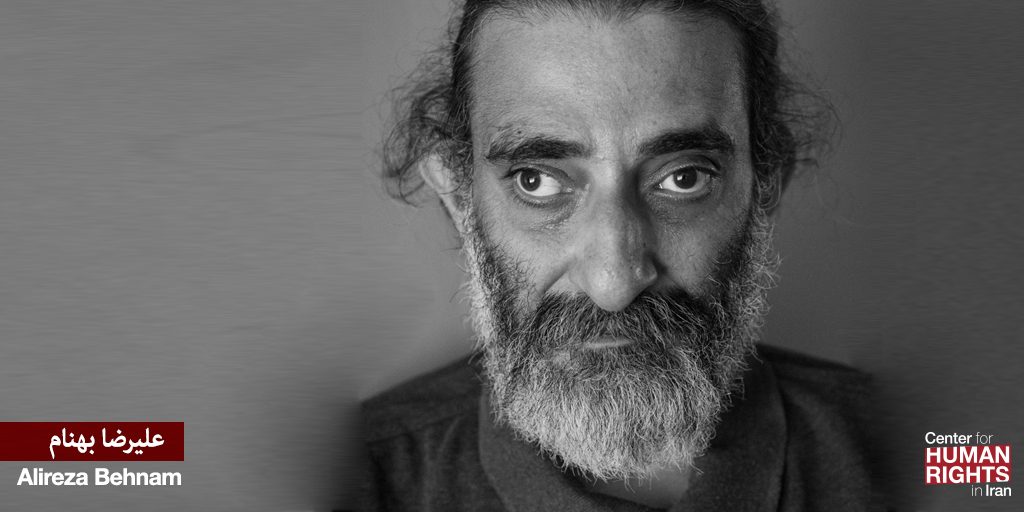

Interview With Literary Figure Alireza Behnam on Censorship

“Authors have learned that they cannot write about things that are against the country’s official religion, or against national security, or anything that promotes ‘moral corruption’ and ‘indecency.’”

State censorship of the publishing industry in Iran is intensifying and increasingly arbitrary, causing book publishers in Iran to become more cautious than ever, according to Alireza Behnam, a journalist, poet and translator. State authorities now frequently ban books after they have already been published with permission from the Culture and Islamic Guidance Ministry, Behnam noted.

In an interview on April 29, 2019 with the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI), Behnam said that during President Rouhani’s current second term in office, state intelligence and security agencies and ultra conservative groups have increasingly succeeded in forcing the Guidance Ministry to remove approved books from the market.

Early on in Rouhani’s first term (2013-2017), the book industry transformed for the better, Behnam said. But more recently the repression of culture in the country has intensified, especially because of the Rouhani administration’s passive reaction to interference by state security agencies.

“When he was first elected in 2013, the cultural scene changed a lot. Many artists who had not worked for years returned to the scene. But the Rouhani Administration, like other moderate governments in the past, has progressively retreated from its positions on culture as it approaches the end of its second term…. To protect its political position, the Rouhani Administration has been bending to every criticism on literary and cultural issues made by various agencies,” Behnam said.

At the current Tehran International Book Fair (April 24-May 4) several books published with permission from the Guidance Ministry were then subsequently prevented by the ministry from being offered to the visiting public.

According to authors and journalists, some of the books banned at the fair include: Women with Mustaches and Men without Beards by Harvard academic Afsaneh Najmabadi; Kucheye Abrhaye Gom Shodeh (The Alley of Lost Clouds) by Kourosh Asadi; Kayhan Khanjani’s novel, Bande Mahkoumin (The Condemned Ward); E’dam va Qesas (Execution and Retribution) by civil rights columnist Emad Baghi; Dine Dowlati va Dowlate Dini (State Religion and Religious State) by Mohammad Ghouchani; Roshanfekri Dini va Chaleshhaye Jadid (Religious Intellectualism and New Challenges) by Iran’s late Foreign Minister Mohammad Yazdi; and Faqihan va Enghelabe Iran (Theologians and the Iranian Revolution) by Hadi Tabatabaie.

In addition to intensifying censorship, the rising cost of paper and people’s decreasing buying power under the current economic conditions have made life more difficult than ever for authors and translators, Behnam noted. The full interview with Alireza Behnam follows.

CHRI: What are the steps for getting the Guidance Ministry’s permission to public a book?

Alireza Behnam: Every book is treated differently. It’s very arbitrary. There are no set guidelines. If a publisher accepts your book, it is first sent to the National Library of Iran to be listed and then the final copy is submitted to the Guidance Ministry.

It usually takes two to three months for the Guidance Ministry to let the publisher know whether it has permission to print it or not. But some books can get stuck in this stage for months or even years. The process can take longer depending on the book’s title, the text and who the author is.

If there’s a need to modify the text, it can be modified and sent back the ministry. It can go back and forth several times. The ministry specifies what needs to be modified and then the publisher informs the author or translator who will make the modifications and then it is sent back to the ministry.

But in recent years a new step has been added to the publishing process. Now the Guidance Ministry can block a book after it has been published… It works like this: They give you permission to publish a book and it gets printed and then they cancel the permit. As a result, the book ends up in the black market without the author and publisher earning a penny. This has hurt the publishing industry.

In January 2019, a poet friend of mine who lives abroad got his book published in Iran and then he was told that it cannot be distributed. He was told that it can be sold only at the book fair on condition that it’s not advertised.

CHRI: Is it possible that permits are rescinded because books get published without the modifications requested by the Guidance Ministry?

Behnam: That’s unlikely. Publishers will not take such a risk. If they have, it’s very rare. Publishers invest a lot of money in books and they don’t want to waste it. In the film industry, you can cut or replace a scene after a movie is made but you cannot change the text after a book gets printed. The printed volumes will have to be destroyed.

Another point I want to make is that many books get printed and distributed after going through all the bottlenecks and then some agency steps in and tells the Guidance Ministry to remove them from the market. The Guidance Ministry in Rouhani’s current term has cooperated with these agencies and quickly complied with their requests. As a result, there are a lot of books that are bought and sold in the black market.

CHRI: Is censorship imposed on authors and translators only through the Guidance Ministry?

Behnam: There are various kinds of censorship. It’s not just state censorship. For instance, we now have economic censorship because the high cost of paper has put a break on many independent publishers. We have media censorship. Major media outlets are very selective in covering literary works and they ignore certain authors.

We even have censorship on individuals. Three members of the Iranian Writers Association (IWA) were arrested for organizing a ceremony to mark the 50th anniversary of the organization. This is censorship. People have the right to assemble and express their views in the presence of like-minded colleagues. But these three writers are being prosecuted. It’s deplorable to punish people even though they have not violated any law.

CHRI: Is there more official resistance toward original works in Persian or translations?

Behnam: The authorities are more sensitive toward Iranian novels and novelists, whether they are well-know or newly arrived. One of the latest examples, which is really sad (and prompted the Tehran Novelists Guild to complain to the Guidance Ministry) is the late Kourosh Asadi’s novel, Kucheye Abrhaye Gom Shodeh (The Alley of Lost Clouds), which was published twice when he was alive and once more after he committed suicide and became a best seller. This year it was not allowed to be reprinted and it was even banned from the book fair. The question is, what changed? The book? Did the author do something wrong? He’s already dead.

CHRI: Are authors and publishers informed by censors in advance regarding the red lines that should not be crossed?

Behnam: There are no guidelines. Over the years, authors have learned that they cannot write about things that are against the country’s official religion, or against national security, or anything that promotes moral corruption and indecency. The red lines are not clearly defined. Every censor acts according to his own taste.

Once I translated a novel by an American author and so did one of my friends. We submitted our translations to different publishers. The censor who read mine threw half of it away. But my friend’s translation was published with just one word changed. It was the same book, with similar translations, but one censor thought part of it was unethical and the other thought it was okay. Consequently, one book was published in full and the other only partially.

CHRI: Have you encountered authors who have not been able to publish any of their books?

Behnam: I have met many authors whose books have not received permission from the Guidance Ministry because they refused to be censored. Instead they published their writings in their personal blogs. We know that these writers will never receive recognition. Many of them have died without ever being known. One example is Alishah Mowlavi. He was never able to get his books published in the Islamic Republic. Only one of his books was published in Paris by Naakojaa. He was 60-something when he died without having a book in Iran even though he was well-known in the literary community.

CHRI: Rouhani made campaign pledges to open up the cultural scene and lift restrictions on artists. But do you feel nothing has changed?

Behnam: The truth is that things have changed. When he was first elected in 2013, the cultural scene changed a lot. Many artists who had not worked for years returned to the scene. But the Rouhani Administration, like other moderate governments in the past, has progressively retreated from its positions on culture as it approaches the end of its second term.

To protect its political position, the Rouhani Administration has been bending to every criticism on literary and cultural issues made by various agencies. The same has happened in previous governments. It has been very easy to knock culture, whether it’s books, films, theater or music.

Last month they banned a comedy from the movie theaters three weeks after it became a box office hit, claiming it was unsuitable. How come no one thought it should be censored before it became a big hit? Another example is musicians who have gone on tour in Iran and performed with permission in 20 cities and then suddenly their concert has been banned in the next city, even though it’s the same music and the same band. Meanwhile the government has quietly stood aside.

CHRI: Do you think it has an impact when, for instance, the Tehran Novelists Guild writes a letter to the Guidance Ministry and complains about censorship?

Behnam: I have not seen any evidence of it making a difference. Objections by the Tehran Novelists Guild can only be as effective as similar actions in the past by other organizations such as those representing actors in the theater and film industry. It’s not difficult to go back and see the outcome after they wrote their open letters. We can imagine that the Tehran Novelists Guild’s letter will meet the same fate.