Political Prisoner Stabbed to Death in Tehran Penitentiary Three Months After Protesting Unsafe Conditions

- Alireza Shirmohammadali Was Unlawfully Held in Ward With Inmates Convicted of Dangerous Crimes

- He Had Gone on Hunger Strike Against Unsafe Prison Conditions Three Months Before His Death

- The 21-Year-Old Was Expecting to Be Released on Bail Soon

- Lawyer: “He was a man of dialogue, not confrontation”

June 11, 2019 – Political prisoner Alireza Shirmohammadali was stabbed to death in the Greater Tehran Central Penitentiary (GTCP) after he was unlawfully kept in a ward that holds inmates convicted of dangerous crimes, his lawyer informed the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

“This was a preventable death and resulted from gross negligence on the part of the authorities,” said Hadi Ghaemi, CHRI’s executive director. “The judiciary has been repeatedly warned of the dangers of its failure to separate political prisoners from inmates convicted of violent crimes.”

“Yet it has refused to heed those calls even after repeatedly seeing the consequences of its failure to act,” he added.

The Greater Tehran Central Penitentiary was built in 2015 primarily for holding suspects and inmates convicted of drug-related offenses. But the judiciary has also used it to unlawfully incarcerate activists and dissidents.

“Unfortunately, the law regarding the separation of prisoners based on the type of crime is not being enforced at the Greater Tehran Central Penitentiary,” attorney Mohammad Hadi Erfanian-Kaseb told CHRI on June 11, 2019.

“Basically, it’s not a suitable place, especially for those held for political reasons,” he added. “I met Alireza in prison once. He was a man of dialogue not confrontation.”

Iranian authorities have not yet commented on the matter.

Since August 21, 2019, Shirmohammadali was held in the GTCP’s Ward 1, Hall 11, sarcastically referred to by prisoners as “the Suite.”

According to Iranian law, prisons are required to divide prisoners according to the nature of their convictions.

Article 69 of the State Prisons Organization’s regulations states: “All convicts, upon being admitted to walled prisons or rehabilitation centers, will be separated based on the type and duration of their sentence, prior record, character, morals and behavior, in accordance with decisions made by the Prisoners Classification Council.”

Three months before his death, Shirmohammadali had gone on hunger strike to protest prison conditions.

“His appeal hearing was scheduled for July 9 and we were very optimistic that he would be granted temporary release on bail until the announcement of the verdict,” said Erfanian-Kaseb. “We had even been given certain assurances.”

Who Killed Alireza Shirmohammadali?

A source with detailed knowledge of the circumstances of Shirmohammadali’s death identified one of the assailants as Hamidreza Shojaie, also known as “Khoroos” (“The Rooster”), who is on death row for murder.

The name of his accomplice, who’s in prison for drug-related offenses, is not known.

The source, who spoke on the condition of anonymity for security reasons, told CHRI that the two confronted Shirmohammadali and stabbed him multiple times with a sharp object.

“The prisoners in the ward said he had been stabbed so many times that he died before the prison guards got to the scene,” added the source.

Arrested on July 15, 2018, Shirmohammadali was charged with “insulting the sacred,” “insulting the supreme leader” and “propaganda against the state.” He was sentenced to eight years in prison in February 2019 and was awaiting the result of his appeal before his death.

Shirmohammadali’s lawyer told CHRI that the young inmate was imprisoned based on content he had posted on social media.

“The charges were based on the things he wrote on his channel on Telegram [messaging app],” said Erfanian-Kaseb. “He did not have a lawyer during his trial in the revolutionary court and I began representing him for his case before the Appeals Court. I only had one visit with him in prison.”

Shirmohammadali had one child and supported his mother financially through a job in the service industry before he was imprisoned.

Authorities Ignored Shirmohammadali’s Hunger Strike Against Prison Conditions

Between March 14 and April 19, 2019, Shirmohammadali had gone on hunger strike to protest the dangers faced by inmates in the ward.

“We went on a hunger strike because of the lack of facilities and threats to personal safety inside the Suite,” Shirmohammadali wrote in a letter co-signed by fellow hunger striker Barzan Mohammadi on April 1, 2019.

“But the safety of our lives is of no concern to the prison authorities and its bosses,” he added. “Just yesterday, Reza Haghverdi, one of the prison guard officers, told us very directly that our hunger strike is going to end with death certificates.”

“We have asked the authorities to look into our requests many times but they have not done so,” said the letter.

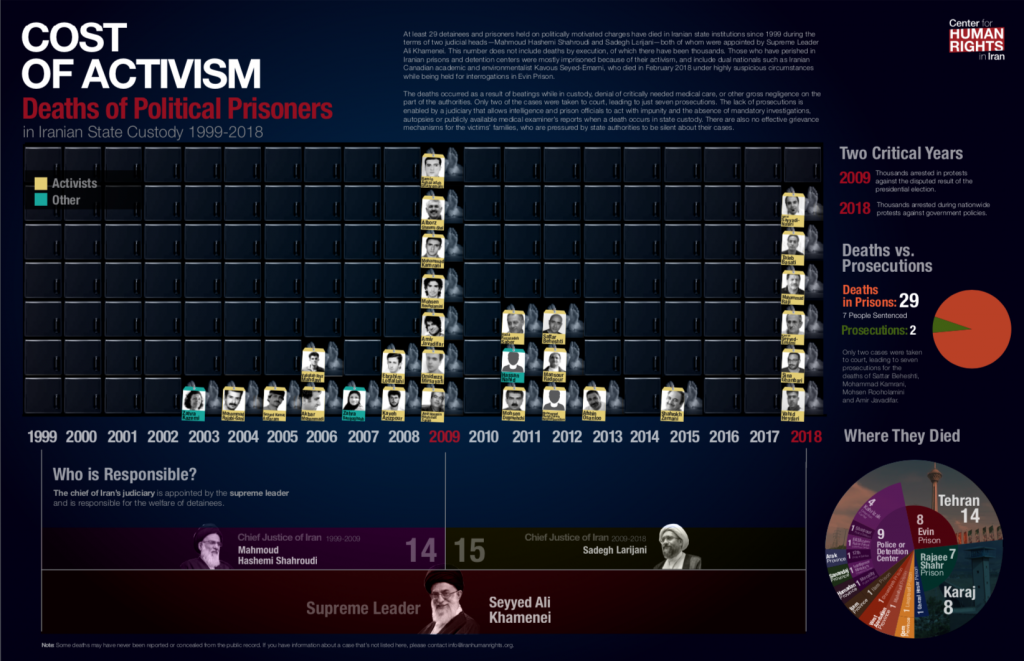

Since 2003, at least 29 political prisoners have died in Iranian state custody, according to investigations by CHRI. That number does not include deaths by execution.

The deaths occurred as a result of beatings while in custody, denial of critically needed medical care, or other gross negligence on the part of the authorities. Only two of the cases were taken to court, leading to just seven prosecutions.

The lack of prosecutions is enabled by a judiciary that allows intelligence and prison officials to act with impunity and the absence of mandatory investigations, autopsies or publicly available medical examiner’s reports when a death occurs in state custody.

There are also no effective grievance mechanisms for the victims’ families, who are pressured by state authorities to be silent about their cases.

In December 2018, Vahid Sayyadi-Nasiri died at the Shahid Beheshti Hospital in Qom after going on hunger strike to protest the denial of his right to counsel and inhumane prison conditions.

Iranian-Canadian academic and conservationist Kavous Seyed-Emami died under suspicious circumstances in Tehran’s Evin Prison in February 2018.

“Political prisoners are dying in Iranian state custody because the authorities are refusing to implement mechanisms to ensure their safety or hold the authorities accountable when deaths do occur,” said Ghaemi.

“These prisoners are usually moved to dangerous wards as additional punishment for speaking out against prison conditions or their cases,” he added.