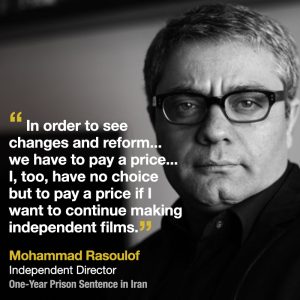

Mohammad Rasoulof’s Films Were Banned in Iran, Now He’s Been Sentenced to Prison

“We have to pay a price, and every person will pay some price,” says acclaimed filmmaker

July 24, 2019 – The sentencing of award-winning filmmaker Mohammad Rasoulof to one year in prison for the content of his films has highlighted the perilous political landscape independent artists must navigate in Iran.

“Iranian cinema has won international acclaim despite stifling censorship and the ongoing persecution of artists,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

“Rasoulof’s only crime was pursuing an artistic vision that didn’t support government narratives about Iranian culture and society,” he added.

Rasoulof was also banned from “membership in political and social parties and organizations” for two years, he told CHRI on July 21, the day after he received the verdict.

Since September 2017, Rasoulof has also been banned from leaving the country and making films.

“The absurd sentence against Rasoulof reflects the high price independent filmmakers must pay for refusing to abide by the government’s restrictive and arbitrary rules,” said Ghaemi.

“My Job is to Tell Stories”

“Strangely, they’re accusing me of ‘propaganda against the state’ for telling stories,” Rasoulof told CHRI. “None of my films are political, they are social criticisms that have political repercussions.”

“Strangely, they’re accusing me of ‘propaganda against the state’ for telling stories,” Rasoulof told CHRI. “None of my films are political, they are social criticisms that have political repercussions.”

“Instead of understanding the films, they are interpreting them as slander against the state,” he added. “I think intolerance and impatience toward criticism is reactionary.”

Independent filmmakers face enormous pressure from the Iranian government to refrain from producing work that is critical of state policies and officially sanctioned narratives on politics, culture and society.

The government subjects all artists in the country to restrictive and arbitrary censorship policies administered by the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance, and has a documented history of persecuting independent filmmakers who resist this pressure.

Several directors have been sentenced to prison and had their films banned in Iran for failing to abide by these rules.

In February 2016, Iranian-Kurdish documentary filmmaker Keyvan Karimi was sentenced to 223 lashes and one year in prison under the charge of “insulting the sacred.”

In October 2014, Iran’s Parliamentary Committee for Cultural Affairs called on the Culture and Islamic Guidance Ministry to ban eight Iranian films that were allegedly pro-Green Movement, including “I’m Not Angry.”

In March 2010, Rasoulof was prosecuted under the charges of “assembly and collusion against national security” and “propaganda against the state” along with fellow prominent filmmaker Jafar Panahi and sentenced to six years in prison.

Upon appeal, the sentence was reduced to one year in prison but was not enforced.

Rasoulof was again blacklisted by the Iranian government after receiving international praise for his film, “A Man of Integrity,” including the top prize in the Un Certain Regard section at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival.

After returning from the Cannes Film Festival to Iran in September 2017, the authorities confiscated his passport and informed him that he was no longer allowed to make films

The film, about a small-town goldfish farmer struggling to make ends meet against systematic corruption, was banned in the Islamic Republic.

Since 2017, he has been summoned and questioned numerous times by the Culture and Media Court.

“In part of his ruling, the judge wrote that the defendant, me, has not made any films about the bravery of my nation,” Rasoulof told CHRI, noting that he was paraphrasing the judge’s words. “Then he mentioned that I have been awarded by non-Iranian film festivals and that foreign audiences clapped for me; they are the enemies of the state and therefore I’m an enemy of the state.”

Rasoulof added that most of the accusations made against him in court were focused on “A Man of Integrity” and another film he had made, “Manuscripts Don’t Burn,” in which he examined the Iranian government’s persecution of members of the Baha’i faith.

“When I was questioned by investigators, I was asked about all my films,” he said. “Their main argument was that I have blackened [the state] and that my criticisms are unhealthy and there’s no hope in my films.”

Rasoulof continued: “I asked the honorable judge, ‘Have you watched my films?’ He said, no… it was sufficient to read the assessment by the security agencies about me and listen to the answers I gave to his questions.”

Pessimism About Appeal Process

Speaking to CHRI, Rasoulof’s lawyer, Nasser Zarafshan said his client’s actions do not amount to “propaganda against the state,” and that he would be filing an appeal against the recent verdict.

“This verdict was based on Article 500 [of the Islamic Penal Code],” he added. “The law says ‘propaganda against the state’ are actions by an individual against the Islamic Republic, but challenging the officials and institutions within the framework of the Islamic Republic is not propaganda against the state. It’s criticism.”

Rasoulof told CHRI he was “pessimistic” about the fairness of the appeal process and “about being heard.”

“I think the judicial system of the Islamic Republic is concerned about protecting the state, rather than enforcing the law,” he said. “I can’t do anything but watch this injustice with sadness and resignation.”

Rasoulof continued: “I think I have to accept that in order to see changes and reform in the structure of the country, we have to pay a price and every person will pay some price. I, too, have no choice but to pay a price if I want to continue making independent films.”