Father of Female Political Prisoner Worries She Has COVID-19 Without Access to Treatment

Fears that the ethnic Kurdish Iranian political prisoner Zeinab Jalalian (also spelled Zeynab) could have contracted COVID-19 in Tehran Province’s Gharchak Prison have deeply worried her family, the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) has learned.

Fears that the ethnic Kurdish Iranian political prisoner Zeinab Jalalian (also spelled Zeynab) could have contracted COVID-19 in Tehran Province’s Gharchak Prison have deeply worried her family, the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) has learned.

“Zeinab phoned her mother last week… and said she was not feeling well,” her father Ali Jalalian told CHRI on June 9, 2020. “She said she had symptoms of the coronavirus disease.”

“After that she has not made any contact,” he added. “We are worried and don’t know what to do. They have taken Zeinab [from the central prison of the city of Khoy, West Azerbaijan Province] to Gharchak and we don’t have the means to travel there to see her.”

For the past 13 years, Zeinab Jalalian, 39, has been serving a life sentence for her alleged membership in the Party of Free Life of Kurdistan (known as PJAK and PEJAK), a banned separatist organization based in the northwest of Iran.

She was transferred to Gharchak Prison, 37 miles south of Tehran in the city of Varamin, last month without prior notice, in violation of Article 234 of the State Prisons Organization’s Regulations, which gives convicts the right to be held in a prison near their place of residence—in her case, in East Azerbaijan Province, according to her father.

In August 2019, 200 inmates in Ward 5 of Gharchak Prison sent an open letter to the head of the State Prisons Organization in Tehran Province protesting the prison’s inhumane living conditions.

In August 2019, 200 inmates in Ward 5 of Gharchak Prison sent an open letter to the head of the State Prisons Organization in Tehran Province protesting the prison’s inhumane living conditions.

In June 2020, CHRI received reports that other political prisoners in Gharchak had been infected with COVID-19 and were transferred to another location in the prison that’s ill-equipped for medical treatment.

“In recent days, eight prisoners who have contracted the coronavirus in Gharchak Prison have been moved and abandoned at an inadequate space without medicine or treatment in the prison clubhouse, which is unsanitary and lacks ventilation,” tweeted formerly imprisoned journalist Jila Baniyaghoob on June 8.

“Some of the prisoners said they contracted the virus from a prisoner who returned from furlough [temporary leave],” she added. “The sick prisoner was not quarantined. She was taken to her cell despite having symptoms of the disease. When her test came back positive, eight cellmates volunteered to be tested and the results were all positive.”

“Other prisoners are refusing to be tested, even though they have signs of the disease, because they are afraid they might meet the same fate as those who tested positive and be abandoned in an inadequate location,” Baniyaghoob said.

“Today the prisoners in quarantine had not been fed until five in the afternoon because the guards are afraid to go there,” she added.

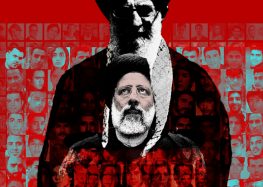

In March, as Iran struggled to cope with rapidly increasing COVID-19 infections, Judiciary Chief Ebrahim Raisi said 85,000 prisoners had been temporarily released to reduce prison transmissions. But political prisoners and dual nationals were mostly excluded despite pleas by the prisoners and their relatives.

To date it is not clear whether Iran has been following the World Health Organization’s (WHO) interim guidance on how to prevent and control the spread of COVID-19 in prisons, which CHRI translated into Persian.

In April 2020, 18-year-old Instagram celebrity Fatemeh Khishvand (aka Sahar Tabar) was hospitalized after contracting COVID-19 in Tehran’s Evin Prison.

“We find it unacceptable that this young woman has now caught the coronavirus in these circumstances while her detention order has been extended during all this time in jail,” Khishvand’s lawyer Payam Derafshan told CHRI at the time.

That month, UN human rights experts called on the Iranian judiciary to expand its temporary release of thousands of detainees to include prisoners of conscience and dual and foreign nationals who are still behind bars despite the serious risk of being infected with COVID-19.