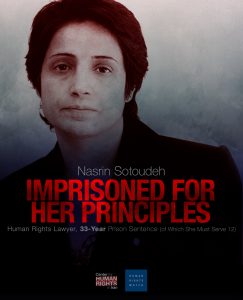

Judiciary Blocks Nasrin Sotoudeh’s Bank Account, Cutting Off Funds for Family

Husband of Imprisoned Human Rights Attorney Says Tactic Aimed at Silencing Family

Husband of Imprisoned Human Rights Attorney Says Tactic Aimed at Silencing Family

Reza Khandan: “They want to send a message to those who are willing to go to prison. What we have to say is we won’t step back”

July 29, 2020—Broadening its assault on human rights defenders and their families, Iran’s judiciary has blocked the bank account of imprisoned human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, her husband, Reza Khandan, told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) on July 27, 2020.

CHRI condemns this blatant attempt to impose additional punishments on human rights defenders and their families beyond the already unlawful sentences applied in kangaroo courts.

“The authorities in Iran have seen that repeatedly imprisoning Nasrin Sotoudeh and other human rights defenders has not silenced demands for basic civil and political rights, so they are going after them extrajudicially to inflict additional pain on their families,” said Hadi Ghaemi, CHRI executive director.

Sotoudeh’s account with Pasargard Bank in Tehran has been blocked since May 2020 on orders of the Tehran Prosecutor’s Office, and efforts by Khandan and Sotoudeh’s lawyer to regain control of the funds have failed, Khandan told CHRI.

Sotoudeh’s account with Pasargard Bank in Tehran has been blocked since May 2020 on orders of the Tehran Prosecutor’s Office, and efforts by Khandan and Sotoudeh’s lawyer to regain control of the funds have failed, Khandan told CHRI.

On July 27, 2020, Sotoudeh’s husband wrote on Facebook: “We believe the prosecutor’s action is aimed at putting economic pressure and financially hurting the family in a time of crisis and economic collapse due to the incompetence and inadequacy of the government and ruling establishments. We will not stay silent in the face of such inhuman actions.”

In an interview with CHRI, Khandan explained: “The account was closed in May but I only recently found out about it. They didn’t inform us. The bank didn’t even send an SMS.”

He noted that when he was in the Prosecutor’s Office he grew suspicious: “I noticed several confidential letters about Nasrin…. One of the letters was about Nasrin’s SIM card. I don’t know what the other letters were about.

“I think [the authorities] aren’t satisfied with the punishment imposed on Nasrin, especially when, despite their expectations, she had not been compliant after coming out of prison the last time.” (Sotoudeh was imprisoned from 2010 to 2013, serving three years of a six-year sentence for her peaceful defense of human rights and her membership in the Defenders of Human Rights Center. Upon her release, she resumed her defense of unlawfully prosecuted individuals and other rights-based legal work.)

Khandan continued: “That’s the indication in the Intelligence Ministry’s letter of February 2018 [that I saw] in Nasrin’s case file at the time of her latest arrest [in June 2018]. The letter stated that Nasrin had a previous conviction and was treated mercifully by the state but she refused to stop her actions against the state, therefore she should be arrested again.

“This behavior is a message to civil rights and political and human rights activists that if they do something, prison is the least they will be facing. The authorities think that prison has lost its effectiveness and dissidents are resuming their activities as soon as they get out of prison. They want to send a message to those who are willing to go to prison.

“What we have to say is we won’t step back. It won’t have an impact on us. But a lot of other prisoners could be affected and their families could fall apart if their savings are confiscated.”

Nasrin Sotoudeh is currently behind bars at Evin Prison, sentenced to 38 years in prison, 12 years of which she must serve before becoming eligible for parole. Among her charges were “encouraging prostitution” for peacefully advocating against compulsory hijab and defending citizens’ right to peaceful dissent.