State’s Online Schooling During COVID-19 Is a Privilege Only for the Well-Off in Iran

Teachers, Families and Students Struggle without Needed Technology in Iran’s Poorer Regions

Teachers, Families and Students Struggle without Needed Technology in Iran’s Poorer Regions

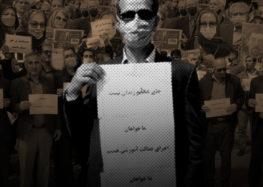

A new online schooling program created by the government to allow virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic will effectively remain a luxury for the well-off in Iran, as Education Ministry officials have shrugged off the inability of many students in Iran’s poor regions to afford the technology necessary to access the program.

With COVID-19 cases surging to all-time highs in Iran, many families have feared sending their children back to school for the new school year. While Iran’s Education Ministry decided to go ahead with opening the schools in most cities—a decision that faced strong opposition as deaths due to the virus have spiked throughout the country—the authorities ostensibly offered a virtual schooling alternative.

The government unveiled the online schooling network, called “Shad” (“Joy”), created by the Education Ministry, in the spring of 2020, when it became apparent that the coming school year might be seriously disrupted by the pandemic.

Yet teachers and families have criticized the network because it requires the use of a tablet or smartphone, luxuries that many Iranian families cannot afford for their children, thus creating a wide gap between the well-off and the poor in education.

On October 24, 2020, a member of Parliament’s Education and Research Committee, Mohammad Vahidi, said 3.5 million students cannot access Shad because they have no internet or the necessary device to connect.

However, on November 2, 2020, Education Minister Mohsen Haji-Mirzaei said in a television interview, “Students without digital devices are not required to receive an online education. They should go to their school instead.” He said only a small number of students would need to physically go to school and therefore the spread of COVID-19 virus would not be a serious issue.

Online Schooling Network Widens Gap Between Rich and Poor

“In the southern parts of the capital where low-income families live, people don’t even have the most basic sanitary material. They cannot afford a tablet or smartphone for their children,” said Ali, a mathematics teacher in Tehran, who spoke to the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) on condition of anonymity.

“The only alternative for students who don’t have the means to buy a tablet, or can’t go to school, was to attend classes on television but the authorities did not take the idea seriously enough,” Ali added.

In March 2020, as school closures became common due to the coronavirus, the state broadcasting organization, Islamic Republic of Iran broadcasting (IRIB), began airing some classes on its channels but the project did not grow into a full curriculum.

“Before COVID, I had 30 students in my class but now at least eight of them are missing,” said Leila, an elementary school teacher in a poor area of the northeastern city of Mashhad.

“Some of them did not enroll in school this year,” she told CHRI, adding that some families have only one smartphone to share among themselves, including for online classes.

Saeid, a teacher in the underdeveloped province of Sistan and Baluchestan, told CHRI that he sometimes holds classes in the open air to reduce the chance of infection.

“Holding classes outside is possible in regions such as Sistan and Baluchestan where the weather is warm, but it’s not feasible in colder places,” he said.

Breakdown in Schooling Leading to an Increase in Child Marriages

Ms. Akrami, a teacher in a village near the city of Bojnurd, in North Khorasan Province, believes lack of access to education in deprived rural areas is causing an increase in child marriages among girls.

“Anything that takes away the opportunity from girls to go to school becomes an excuse to marry them off as young as nine-years old,” she said.

In Iran, girls can be legally married at age 13, and younger with the consent of the father (or male guardian) and a judge. The National Organization for Civil Registration statistics for the Iranian year 1397 (March 21, 2018 – March 20 2019) show there were 13,054 marriages of girls under the age of 13 and 133,086 marriages of girls between 13 and 18. These numbers include only official marriages and thus are significant undercounts; in many cases families do not register child marriages, only officially registering them after the bride is older.

The problem is more prominent in North Khorasan Province where the number of child marriages was already high. In the Iranian year 1397 (March 21, 2018-March 20, 2019), 1,054 girls between the ages of 10 and 14 were married in that province alone.

“If the remote programs could be accessed by all students in the education system, we could reduce discrimination in many regions, but instead, lack of access has created greater discrimination and left many students depressed, partly because more than ever they are becoming aware of their inadequacies in gaining an education,” Ms. Akrami added.

Desperation Increases Among Deprived Students

On October 10, 2020, eleven-year-old Mohammad Mousazadeh committed suicide because he did not have a device to do his online homework.

“I bought my son a mobile phone so he could do his homework until it broke and I promised to get him a new one at the first opportunity,” the boy’s father Adel Mousazadeh was quoted as saying.

The mother, Fatemeh Najjar, said: “Mohammad was in fifth grade. He was a smart and good student. But with this coronavirus situation he needed a smartphone for his classes and lessons.

“The only phone we had at home was broken and Mohammad could not submit [his homework.] It was a bad situation. He wanted a phone from us so that he could study without being bothered.”

Mani, a 14-year-old student in the city of Paveh, Kurdistan Province, became a human courier, carrying goods on the border of Iran and Iraq, to earn money to buy a phone for his school work. On November 10, 2020, he slipped from a mountain and was badly injured.

And on September 14, 2020, nine-year-old Mostafa went on top of a mountain near his village in South Khorasan Province to get a Wi-Fi connection and download school material. But he fell and seriously injured his eye.

“Even if some students in rural areas and small towns could afford a phone or tablet, there’s the issue of internet availability which is a problem in many parts of the country,” Ms. Akrami told CHRI.

She added: “In other poor areas of the country where there’s no possibility of learning online, some of my colleagues copy school materials and personally distribute them among students.”

The State and its Charitable Organizations Not Fulfilling Mandate to Educate, Help Poor

“Some charity organizations have tried to distribute phones and tablets but in these bad economic times, such items have become very expensive and these organizations are not able to meet student demands in poor areas,” Ms. Akrami said.

Based on Article 30 of Iran’s Constitution, “The government must provide all citizens with free-education up to secondary school, and must expand free higher education to the extent required by the country for attaining self-sufficiency.”

In addition, Iran’s parastatal religious foundations, such as the Mostazafan Foundation, The Headquarters for Executing the Order of the Imam Khomeini (also known as Setad) and Astan Quds Razavi–which are now among Iran’s largest business conglomerates and have significant resources —were established to serve the needs of the poor, including in areas such as education. Nevertheless, the online schooling needs of the Islamic Republic’s deprived children continue to go unmet.

Read this article in Persian