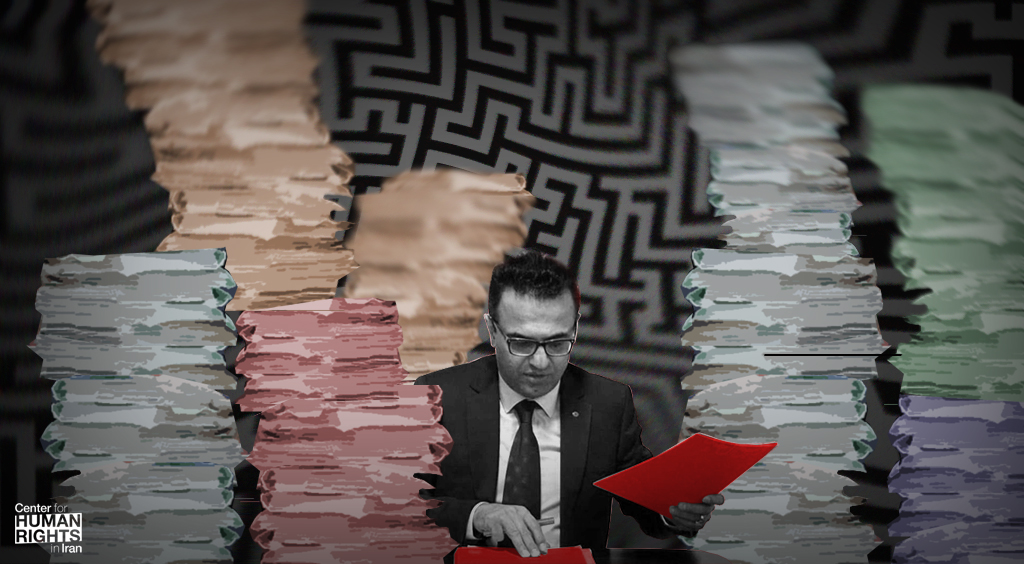

Walking in a Minefield Without a Map: The Life of an Iranian Human Rights Lawyer

Editor’s Note: This article was written by a defense attorney who has represented many detainees held on politically motivated charges in Iran.

At least nine defense attorneys are currently imprisoned on trumped-up charges in Iran for taking on cases involving detainees persecuted by the state for practicing peaceful activism, freedom of speech and expression, or other human rights. Among them is the renowned human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh, who was jailed for defending women arrested for removing their hijabs in public, and Mohammad Najafi, who was thrown behind bars after alerting local news media that a young street protester had died under suspicious circumstances while in state custody.

by Saeid Dehghan

Taking on human rights cases in Iran is like walking in a minefield without a map. As in “The Stream and the Stone,” a Persian story in the form of a poem by Malek-ol-Shoara Bahar that’s taught to school children, lawyers must learn how to find their way between rocks and stones, yet every year there is less water in the stream and the rocks are bigger and sharper. This is because the legislature and judiciary keep adding new obstacles in the form of laws and directives that make it extremely difficult for defense lawyers to effectively defend their clients, and for detainees to receive due process that’s in line with internationally recognized standards.

To understand these obstacles, I will describe here briefly some of the common daily occurrences in the life of an Iranian human rights lawyer.

1- A worried, desperate relative of a detainee arrested for political reasons contacts me and requests a meeting outside my office. The client is extremely afraid of being caught talking to a lawyer. My professor and mentor taught me that all meetings must take place in the office but I know I have no choice but to agree to her request, as I have in similar cases.

When I arrive at the meeting point, she tells me what other family members of political prisoners have experienced: She was pressured by intelligence agents to be silent and avoid hiring lawyers specializing in human rights cases. Yet she is seeking my help because she does not trust the lawyers who’ve been recommended by the authorities that arrested her loved one.

2- I tell her to be calm. I emphasize that a lot of the pressure and intimidation is aimed at scaring relatives, but that she must be strong. We agree that I will start tomorrow.

3- In the morning I think about what I should wear for my appearance at the security court at Evin Prison (courts are sometimes located inside prisons in Iran). Wearing a tie is not technically banned, though doing so is looked down upon by Islamic Republic officials, which abhor Western symbols. I know it could negatively impact my client’s fate in the revolutionary court system, so I decide not to wear one.

4- To enter the courthouse, I must go through a side gate and a main door of the prison. I have to leave behind my briefcase, mobile phone, watch, and pen before entering the main door, leaving the items with agents trained in surveillance methods. I can only carry a case folder inside the courtroom.

I submit to a full body search and the agents carefully check the papers in my folder. Once I’ve gone through the main door, soldiers ask me who I want to meet so that they can coordinate with officials in the relevant section. Then begins the waiting, and back and forth that could stretch on for days or weeks. Usually I am told “Haji (the investigator) is not in today,” “Haji said no one should be allowed in today,” “The case has not progressed that far; there’s no need for a lawyer at this time,” or “This is a security case and your name is not on the list of lawyers approved by the judiciary…”

5- After several days, I finally get inside the courthouse. The first thing I hear is the investigator saying, “Why do you accept these problematic cases all the time? Get a life!”

In Iran’s judicial system, investigators–who are intelligence agents acting with impunity whenever the cases involve human and civil rights issues–are allowed to pressure judicial officials to bring certain charges on zero or scant evidence and easily influence the outcome of a trial. Indeed, if you are detained for political reasons in Iran, you are presumed guilty until proven innocent, which is a difficult feat when the entire system is rigged against you.

When I stand my ground, he changes his tone: “Your client is a spy and it’s possible that you, too, could be charged with espionage and become our guest in Evin.” I mention to him that by law every detainee has the right to a lawyer and if it is not going to be me, they would have to appoint one. “Don’t worry about that,” he says and goes on, “By law, only lawyers on the judiciary’s list can work this case and since your name is not on it, I can’t accept your representation.”

After a long and difficult discussion, he reluctantly accepts my arguments that a) The judiciary’s list is seriously flawed, not approved in a full session of Parliament, and a violation of Article 35 of the Constitution regarding the right to choose a lawyer and b) the Note to Article 48 of the Code of Criminal Procedure states that the list should be approved and signed by the judiciary chief but he has not done so and c) The judiciary chief himself has expressed opposition to the list and perhaps that is the reason he has not signed it and d) The existence of the list in some cases has resulted in serious corruption because it only includes a few hand-picked lawyers and finally e)I doubt you expect the detainee to trust a lawyer appointed by the judiciary instead of choosing an independent one, particularly when he has been charged with a political crime in a case brought by the government in a court where the judge and prosecutor are also appointed by the state.

6- Ultimately, I am allowed to represent my client if I agree to several conditions that essentially make my representation meaningless. I agree, hoping that as the case proceeds I can change the conditions. The power of attorney document is sent over to my client in his cell to sign as he is not allowed to meet anyone, not even his lawyer.

I am verbally informed of the charge against my client without permission to access the case file to see the details. This is based on Article 191 of the Code of Criminal Procedure which is used by the Intelligence Ministry and the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps’ (IRGC) Intelligence Organization to appoint their agents to act as judicial associates in security cases.

7- After many visits to the court, long negotiations and several official requests, I am finally given permission to see my client in Evin Prison’s Ward 2-A, controlled by the IRGC, for 20 minutes, even though the law allows an hour. The meeting is held in the presence of IRGC agents and recorded by security cameras, which makes my client uncomfortable. My verbal and written objections to these unlawful conditions are submitted to security authorities whose reactions are predictable.

8- About an hour before a hearing to present my client’s final defense, I am permitted to read the thick case file. I have time to go through no more than 20 percent of the documents and take notes. Nevertheless, I have to defend my client.

9- In discussions with judicial and intelligence officials, the only charge verbally relayed to me against my client is espionage. State media outlets have dutifully repeated the same accusation in their reporting, as is custom. However, during the trial three new charges are read against my client and immediately I have to come up with a suitable defense. I am given one day to present my client’s final defense; obviously not enough time for a comprehensive response.

10- Eventually the court rejected the espionage and one other charge, which I conceal here to protect my client’s identity. When I mention the case outcome to reporters working for state media outlets, the authorities try to deny and conceal the facts, even from my client. Three weeks later, when I meet my client to inform him that he has been acquitted of two of the charges, he is so happy that I know the authorities have not told him the truth. In fact, they had fed him false information to make him lose hope.

11- When his case was sent to the Revolutionary Court for the two other charges, I made every effort to prevent it from going to Branch 15 or Branch 28, which are presided by judges who are known well for obeying orders from intelligence agents and officials. But the case did end up at Branch 15; the authorities insisted it was a “special” case.

12- On two occasions, Branch 15 summoned to court my client without my knowledge to extract false signed statements that adversely affected his defense. Detainees are summoned without their lawyers’ knowledge to diminish their counsel’s influence and credibility, leading to adverse outcomes for the detainee.

13- My colleagues and I are prevented from bringing mobile phones into courtrooms, yet judges often make use of them inside the courtroom for quiet conversations. This makes court proceedings more stressful knowing that they could be receiving instructions on how to rule on the case.

14- By law, all courts must give a copy of their rulings to defendants or their lawyers. For years, the Revolutionary Court has refused to do so, forcing lawyers to copy verdicts by hand. This is to prevent us from providing them to media outlets, to protect the court from being exposed for its unjust processes.

15- When detainees object to rulings issued by the Revolutionary Court in Tehran, the cases are decided by two specific branches of the Appeals Court located in the same building. I do my best, but fail, to avoid Branch 36–because of its direct ties to the intelligence establishment–but that is where the case landed and the ruling from the lower court was ultimately upheld. When the Supreme Court was petitioned to review the case, it was referred to and rejected by Branch 38, which is also linked closely to intelligence agencies.

Although Article 450 of the Code of Criminal Procedure obliges the Appeals Court to convene to hear objections to preliminary sentences that include prison terms, Judiciary Chief Ebrahim Raisi received Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei’s extrajudicial permission preventing the presence of the defendant or lawyers at appeal hearings, thus ensuring that sentences against political prisoners are upheld.

16- Human rights cases are often handled from start to finish by specific authorities and judges in the Revolutionary Court all the way up to the Supreme Court to satisfy the wishes of intelligence authorities.

17- During the judicial and security processes, I usually receive suspicious calls, overt and covert threats and unlawful summons. Sometimes I am myself subjected to interrogation.

I do not allow these experiences to affect my work. Throughout the years, they have become normal for me. However they do, at times, scare off clients in the private sector who often make excuses to cancel legal representation by attorneys who take on human and civil rights cases. This has become a difficult challenge for many of my colleagues and me who want to accept human rights cases, which provide little to no compensation. Not only do I have to walk a minefield without a map, but I also struggle to make a living.

Saeid Dehghan is an Iranian human rights lawyer and active member of the Iranian Central Bar Association and International Bar Association.

Learn more about Iran’s endangered legal defense profession here.