Interview: Mina Khani on the “Serious Ramifications” for Women in Iran’s New Population Growth Law

Mina Khani is an author and active member of Iran’s women’s and civil rights movements.

A new law ratified by Iran’s Parliament that’s officially aimed at population growth was designed to the detriment of women in the country, the prominent gender rights activist Mina Khani told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

“In a country like Iran, with all its reactionary laws concerning women and severe economic pressures, more laws that further restrict access to contraceptives will have serious ramifications,” said Khani in a Persian-language interview conducted by CHRI and translated below into English.

Khani, a dancer, theatre actress and writer emigrated from Iran to Germany at the age of 19.* Currently based in Berlin, she has remained an active member of Iran’s feminist and civil rights movements by examining these issues—severely censored in the country by the government—through her performance art and commentaries in articles, books, and digital media

“Social patriarchy cannot be separated from existing laws. The laws and the state’s propaganda machines promote and strengthen social patriarchy,” said the 38-year-old outspoken member of Iran’s “Me Too” movement. “They turn it into an ideology, making it systematic. The same system that commits sexual violence is also engaged in systematically destroying women’s financial independence.”

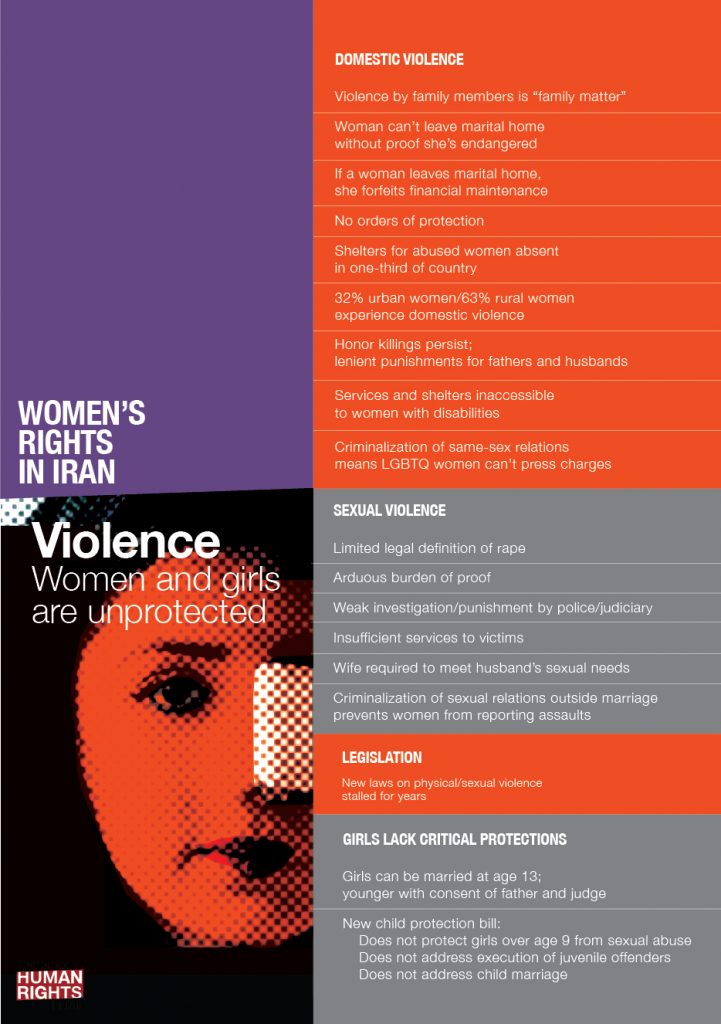

CHRI: Iran’s Parliament recently ratified a law aimed at population growth that discriminates against women. The law could have multiple negative effects on women including increased child marriages and unwanted pregnancies, and the spread of disease among women due to restricted access to contraceptives. Why do you think it was passed now?

Khani: In free societies, ownership of the body is one of the most fundamental subjects of debate in discussions regarding emancipation. When we discuss emancipation, we’re not just referring to women’s right to comfortably walk in public without fear of being sexually assaulted at any moment. No!

When we talk about emancipation, we are referring to political, economic, and social opportunities that women gain from liberation. This law or plan for population growth has specific stipulations that are totally in line with policies aimed at making women stay at home, such as the ban on abortion and basically using women’s bodies as reproduction machines.

When there’s an emphasis on viewing girls and women as potential mothers, that means they will be further held back from society. Even in some European countries where there have been attempts to define fertility within the context of women’s professional statuses in a specific economic system and provide them with greater space, we see that when women have children, they are to some extent held back from economic activity. In these societies, the decision to have children should be based on job status and available time.

In a country like Iran, with all its reactionary laws concerning women and severe economic pressures, more laws that further restrict access to contraceptives will have serious ramifications.

If you listen carefully to [Supreme Leader] Ali Khamenei’s speeches in recent years, you will notice that he’s adamant about fertility and population growth. In previous years, however, the government had concluded that it was necessary to control population growth to some extent. That changed when the ruling establishment tilted toward militarism.

Civil society has missed this important point, that there’s a very strong connection between the Islamic Republic of Iran’s desire to become a major power in the region and its insistence on using women to increase the population. When the ruling establishment wants to pursue a military strategy, it always encourages people to have more children. On the other hand, when wars end, it tries to discourage population growth.

When the war between Iran and Iraq came to an end, the government began to implement policies to control the population. Families were advised to have one child, or two at most. Of course, this was not in line with the Islamic Republic’s ideological foundations, which still consider women as nothing more than reproduction machines. Still, there were several reasons behind the population control policies during those years. For example, there was a gender imbalance since the number of men in the population had fallen and there was a crisis of families without guardians. The Islamic Republic had to tackle those issues.

Today the Islamic Republic is pursuing a militaristic policy. Militants always need soldiers to die for them. All the militaristic regimes, namely Nazi Germany, have encouraged mothers to have more children. All the societies that are engaged in war have encouraged fertility, even among the poorest sectors. In times of war, there’s always a strong bond between this view—of women simply being bearers of children—and militaristic policies. We can see them developing concurrently today in the Islamic Republic.

In previous years, some women’s organizations tried to fight against such laws by distributing free contraceptives in poverty-stricken areas. There were also grassroots groups that campaigned to stop the spread of AIDS. The latter were not concerned with just distributing free condoms or other contraceptives. They also inspired debate on what should be done to prevent AIDS from being transmitted.

Now the Islamic Republic is passing laws of this type [discriminatory against women], confronting civil rights activists and curtailing freedom of speech to prevent the emergence of grassroots social movements and establish its own social order.

CHRI: In your opinion, are there types of discrimination against women that have been overlooked in Iran?

Khani: Often the relationship between sexual violence and economic violence against women in Iran does not get discussed. Often the two issues are raised in opposition to one another. There seems to be a certain group that is trying to promote the state’s version of domestic violence that portrays the problem as exclusive to middle- and upper-class women.

I think we must clearly define “middle class” because middle-class women are still enslaved and don’t have the economic independence we expect. They don’t own property, or if they do, it’s limited. The economic benefits of the middle class are largely controlled by men. In other words, the same discriminatory anti-women laws are empowering men to carry out economic violence against women. These include symbolic examples, such as receiving lesser inheritance and blood money, as well as women’s pathetic share of the job market.

A large number of university seats are filled by women, but their share of the job market is smaller. This is another example of the cycle of inequality and discrimination. Statistics show that at present, women makeup 18 percent of the workforce. Many of them are from the lower classes who earn a lot less than the men. What this tells us is that 82 percent of women do not have a direct and independent source of income. Under such circumstances, the state is enforcing laws to further restrict women’s freedom and choices—from when they should get married, to having children, to where they can live and work. This is precisely in line with the state’s policy to make women economically destitute. This will only exacerbate the country’s economic situation and deepen class differences. The economic situation is so critical that most people are already becoming destitute, but the experience for women has been much worse.

Women’s lack of income independence increases the possibility of sexual violence as well. For example, employers can easily commit sexual violence against female employees who are dependent on receiving a salary and therefore won’t protest.

CHRI: Has this type of discrimination against women received attention?

Khani: Around the world there have been debates and discussions that present poverty as essentially an issue facing women. But the situation of women in Iran and a few other countries is unique. These special characteristics are often overlooked and ignored. Unfortunately, portrayals of discrimination against women lack any reference to the relationship between economic discrimination and gender discrimination. In other words, when there’s a discussion about discrimination against women, discriminated women are unfortunately presented like most of them have a good or average economic standing.

What I would like to emphasize is that this is not just the prevailing view in the media. Those who insist on pointing out class differences also fail to see the link between class and gender, or they don’t think it’s worth much attention. They think most women civil rights activists are well-off and only interested in gaining basic rights, like the right to control their body or to choose what to wear. There is a strong link between laws that make the hijab mandatory and the patriarchal society that takes away women’s financial independence.

CHRI: Do you mean that different forms of discrimination are interlinked?

Khani: Social patriarchy cannot be separated from existing laws. The laws and the state’s propaganda machines promote and strengthen social patriarchy. They turn it into an ideology, making it systematic. The same system that commits sexual violence is also engaged in systematically destroying women’s financial independence. These two work hand in hand. Therefore, paying little or no attention to these facts obscures their existence. In fact, instead of reaching a common understanding, labor and women’s movements often clash on this matter.

CHRI: How do they clash?

One of the organizations that was leading the campaign against [Iran’s] compulsory hijab never mentioned economic issues and when it did, it was generally unrelated to the hijab issue itself. For this reason, it was only seen [in Iran] as a struggle by middle-class women seeking to make the hijab voluntary. On the other hand, leftist movements have prohibited any discussion about the hijab issue. The problem was that neither side saw the interconnectedness of economic and gender discrimination.

As a leftist, I have always participated in discussions and debates about various issues on social media and followed the issues about class struggle. All these discussions had references to “middle-class movements.” The leftists have always referred to women’s movements and anti-discrimination campaigns as “middle-class movements” and have thought of them as simply pursuing the interests of middle-class women, rather than those of the poor and working classes.

The women’s movements against gender discrimination are deserving of some criticism but at the same time we must take note that eliminating some aspects of gender discrimination can empower women economically. For instance, you cannot say that compulsory hijab doesn’t lead to economic violence against working-class women. Why? Because compulsory hijab is one aspect of gender separation according to the dominant ideology, which limits women’s participation in many professions and marginalizes a larger percentage of them.

The class structure of women in Iran is very particular and directly tied to the compulsory hijab issue. If an Iranian decides not to conform to hijab laws as an act of civil disobedience, she is punished with a fine, and if she doesn’t have the means, she will be flogged. In other words, it is harder for women with lesser economic means to fight against forced hijab. This example alone shows the strong interconnectedness of economic and gender discrimination, but it is overlooked in the political discourse.

CHRI: Many believe that future changes in Iran will include the realization of many of the demands of the women’s movement. Do you agree?

I think that’s a correct assessment. A new generation of women has joined the struggle against gender and class discrimination. Many of these women have joined the movement independently, some from the margins of society. Those such as Sepideh Qoliyan have joined the struggle independently without any connection to intellectual movements or political circles and have broken the stereotypical views about women in the struggle against gender and economic discrimination. They have shown that they are concerned not only about gender discrimination, but other interconnected issues as well.

In recent years there has been an increase in the number of women who have been participating in civil activities and struggles against various forms of discrimination. The reason behind this phenomenon can be analyzed from different perspectives.

On the one hand, economic violence has affected mostly women, due to their gender and the nature of the ideological state in Iran. On the other hand, as the political landscape became unstable and various political factions such as the reformists lost ground, civil rights activists got a chance to focus more on gender and class discrimination. In fact, the radicalization of the social and political climate has enabled some lesser-known activists to be better heard.

At the same time, we should acknowledge the powerful impact of social media. It has freed political and social discussions from the clutches of certain individuals and allowed grassroots individuals to express themselves. These social networks are more capable of reflecting the internal situation. We are hearing voices that were once silent but their position in the movement has not been solidified. The old political structure and outdated views persist and there has been no real change.

For instance, we can point out the “Me Too” movement. Many women wanted to come forward and speak about experiencing sexual violence and abuse but lack of economic independence and social limitations held them back or forced them to speak cautiously to avoid being identified.

It’s a common myth that women who come forward to describe sexual violence against them are doing so to seek attention. Based on my research, most of these women are only known among activists and, with few exceptions, they are not recognized by the public. This, too, ties with the issue of economic independence.

At the same time, rape is inappropriately defined in the country’s laws. It’s wrongly referred to as zina, which deals with religious morality rather than sexual violence. For a long time, the “Me Too” movement in Iran was seen as a middle-class phenomenon but many of the victims protested, noting that they are not economically advantaged and don’t have a good life.

CHRI: Why does Iran’s government treat peaceful women’s rights activists as “national security” threats?

Khani: There are two important aspects of the Islamic Republic. One is economic corruption and the other is ideological authoritarianism. So how does the Islamic Republic maintain this corrupt economic, social and political structure with its ideology? Why doesn’t it crumble? How bad can inflation get? How can they solve growing poverty? How are these incompetent officials holding on to power despite a mountain of issues?

The short answer is that it’s a dictatorship but that’s insufficient to describe the status quo. As a dictatorship, the Islamic Republic is different from the German dictatorship of the 1930s and 1940s. Ideologically, the Islamic Republic establishes order by controlling women’s bodies and separating them from men. As soon as this gender dynamic changes, the Islamic Republic’s ideological order will crumble, and its corrupt structure will fall apart.

The ruling establishment is aware that in order to maintain this corrupt economic and political structure it needs an ideological order, an order that is greatly focused on controlling women. In a way, women’s participation in civil and political struggles is a challenge to the existing ideological order and that’s why the Islamic Republic is particularly harsh and violent in dealing with women activists.

At the same time, the authorities try to undermine the social standing of women activists and limit their impact by making accusations that are rooted in the patriarchal nature of society. Sometimes the suppression of women activists creates internal friction and prevents the emergence of a consensus view of the ruling ideological order and it weakens women’s movements. The regime is aware of this and for a long time tried to take advantage of it.

For example, since the 1980s sexual violence has been an issue inside prisons but it was never raised until recently by Sepideh Qoliyan, Narges Mohammadi, Atena Farghadani, and others.

In the 1980s, sexual abuse in prison was kept under wraps. It was considered taboo. For this reason, women political and civil rights activists who are willing to be outspoken and endure all the false labels are considered very dangerous by the Islamic Republic.

Read this interview in Persian

*This article was modified on January 20, 2022, to note that Mina Khani migrated to Germany at the age of 19.