Nouri Conviction by Swedish Court a Triumph for Iran’s “Seeking-Justice” Movement

Conviction Opens Door for More Trials Against Officials Accused of Atrocities

Conviction Opens Door for More Trials Against Officials Accused of Atrocities

July 14, 2022 — After 92 sessions of a trial that lasted almost a year, a court in Stockholm, Sweden convicted Iranian judicial official Hamid Nouri of a “serious crime against international law” and “murder” for his complicity in mass executions of thousands of political prisoners in Iran in summer of 1988.

“This trial and conviction are historic because for the first time in 43 years, since the inception of the Islamic Republic, an Iranian official has been held accountable for mass atrocities,” tweeted Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

“Unlike thousands of political prisoners who were executed without due process based on their religious and political beliefs in Iran in 1988, Hamid was tried in a democratic country through a fair and lengthy judicial process that granted him every avenue to prepare a thorough defense,” said Ghaemi.

“The Islamic Republic has spent decades trying to conceal evidence of its crimes against humanity and cast doubt on the facts,” he added. “The government has destroyed mass graves and blocked attempts to seek information about the executed prisoners.”

“The trial has documented and sealed in the historic record the Islamic Republic’s mass atrocities through testimonies by dozens of witnesses who testified that Nouri was present at the mass executions of 1988,” said Ghaemi.

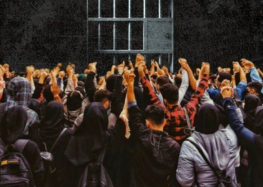

The conviction is also historic moment for Iran’s burgeoning “seeking-justice” civil rights movement, which aims to hold Iranian officials accountable for rights violations.

The trial would not have been possible without testimonies by members of the movement, which is comprised of former political prisoners, family members of individuals executed by the state, as well as rights advocates and dissidents.

Nouri (also spelled Noury) said he was not at the locations where the executions took place, but witnesses testified that he was present at the executions.

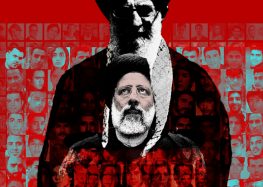

In July 2021, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Situation of Human Rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran Javaid Rehman called for an impartial inquiry into the state-ordered mass executions of 1988 in Iran, and the role newly inaugurated Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi played in those executions.

Political prisoners executed in the summer of 1988 were sent to the gallows by “death commissions” comprised of a small group of clerics who decided the fate of thousands of prisoners—who had already been tried and convicted—based on their answers to questions regarding their religious and political beliefs.

More than three decades later, anyone accused of opposing state policies in the Islamic Republic can be detained on manufactured charges and sent to prison under lengthy sentences issued by kangaroo courts.

Nouri’s trial followed internationally recognized standards of due process and was held in a democratic country; none of Nouri’s victims enjoyed any of the rights that he was granted throughout his trial.

Families of Victims Banded Together to Provide Witness Testimonies

In the Islamic Republic, activists and dissidents are routinely prosecuted and imprisoned for peaceful actions, while officials involved in mass atrocities maintain immunity and rise through the ranks of power. The Nouri case is the first time an Iranian official has been tried and convicted for his involvement in crimes against humanity.

According to Iraj Mesdaghi, a former political prisoner and key witness who was instrumental in helping prosecutors bring the case to trial, “we believe that after Nouri has been sentenced, the pursuit of others responsible for the 1988 massacre will commence.”

The trial of Nouri, 60, who was detained in Sweden in 2019, began in August 2021 and ended in May 2022. The preliminary sentence was announced on July 14, 2022.

According to the indictment brought by Swedish public prosecutors, he was accused of “intentionally killing, together with other perpetrators, a large number of prisoners who sympathized with various left-wing groups and who were regarded as apostates” as well as “crimes against humanity.

The historic trial against Nouri heard testimony by dozens of witnesses, many of them former political prisoners or families of prisoners executed by the state, most of them members of Iran’s “seeking justice” movement.

Unlike in the Iranian judicial system, where internationally recognized standards of due process are regularly flouted and defendants are denied access to counsel of their choice as well as access to digital devices, Nouri had access to lawyers, was able to make statements through the media and was able to utilize a personal tablet throughout his trial.

Most importantly, Nouri and his legal team were granted a year to prepare a thorough defense.

In Iran, defendants can be denied access to lawyers for months while they are interrogated and held in solitary confinement. They are then forced to choose counsel from a list of lawyers chosen by the court. The attorneys are only allowed days or sometimes even only hours to prepare a defense.

Before Nouri’s trial began, Iranian human rights lawyer Saeid Dehghan tweeted about the differences in the Iranian and Swedish judicial systems while referencing a case involving a champion wrestler, Navid Afkari, who was swiftly executed in Iran after being denied due process.

“Nouri’s trial in Sweden’s monarchy will be held during 72 sessions lasting 9 months, with 3 lawyers, and his punishment will be something other than execution,” tweeted Dehghan in November 2021. “But in Iran’s Islamic theocracy, Navid Afkari was [sentenced to death] after a three-hour trial behind closed doors without his chosen lawyer or a chance to defend himself.”

Nouri’s trial and conviction are the greatest achievement so far of Iran’s seeking-justice movement. The conviction, through a fair judicial process, has revealed the Islamic Republic of Iran’s crimes against humanity to the world and emboldened Iranian human rights activists to continue pushing for justice against gross human rights violators through courts in democratic societies.

Nouri’s trial would not have been possible without the ceaseless struggles of victims’ families and activists in documenting these crimes despite the Islamic Republic’s brutal suppression of the evidence and facts involving the state’s mass killings of 1988.