More Prisoner Deaths Feared in Iran’s COVID-Infested Jails

Authorities Deny Prisoners Medical Treatment and Safety Measures

Authorities Deny Prisoners Medical Treatment and Safety Measures

Despite a renewed wave of COVID-19 infections in Iranian prisons, a growing number of infected political prisoners have been denied proper treatment, raising fears of more unnecessary deaths of prisoners in state custody.

In a non-exhaustive study, Amnesty International has reported that at minimum, 92 men and four women in 30 prisons across Iran have died in state custody since January 2010 due to deliberate denial of access to adequate healthcare.

The number, which is illustrative but not comprehensive, includes the poet Baktash Abtin, who died in Iranian state custody in January 2022.

In a formal inquiry, UN human rights experts, including the Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, noted that they were “gravely concerned that his death followed a prolonged period during which Mr. Abtin was in a critical health condition, including due to having contracted COVID-19, during which he was denied access to appropriate and timely medical care.”

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), people in prisons and other places of detention are more vulnerable to COVID-19 due to their confined living conditions.

In Iran, this risk is heightened due to severe, documented overpopulation, insufficient cleaning and hygiene supplies, as well as the absence or denial of adequate medical treatment.

The Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) calls on the international community, including the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, the Human Rights Council, the special rapporteur for human rights, and all Member States to demand that the Iranian authorities provide immediate and full treatment for all prisoners, including political prisoners who have long been targeted for denial of medical care.

In particular, CHRI urges the international community to demand that ailing prisoners be immediately released for full care in proper medical facilities.

Denied COVID-19 Treatment and Testing

After testing positive for COVID-19, internationally-acclaimed filmmaker Jafar Panahi was briefly taken from Evin Prison to a hospital for treatment but was quickly returned to the prison on August 7, 2022, where he was held incommunicado, according to his wife Tahereh Saeidi.

“When Jafar was transferred to Taleghani Hospital we thought he was going to be quarantined there but very suddenly [the authorities] removed the serum [from his arm] and said has to be returned to [Evin] Prison,” Saeidi told Radio Farda on August 8. “Since then, I haven’t heard anything. It’s very unlike Jafar that he wouldn’t call [from prison]. This isn’t a good sign. I’m very worried.”

Panahi was arrested on July 10, 2022, after engaging in an online campaign calling on state security forces to “lay down your gun” and stop shooting protesters.

Panahi, who was arrested along with at least 15 other people in a major crackdown on dissent, was forced to begin serving a politically motivated six-year prison sentence that had been issued in 2010 in “suspended” form, meaning it could be enforced at any time.

Imprisoned human rights attorney Amirsalar Davoudi, held in Ward 4 of Section 2 in Evin Prison, had a fever and body aches for at least three days starting on August 4 but was not given a COVID-19 test or any medical treatment.

Meanwhile, on August 1, Esmail Gerami, a board member of the Pensioners Council of Iran who is 68 and serving a four-year prison sentence, contracted COVID-19 while in detention in Evin but was denied proper treatment.

“The officials transferred him to… Taleghani Hospital for further examination, but due to the lack of a specialist, he was sent back to the prison,” according to the Council’s news service.

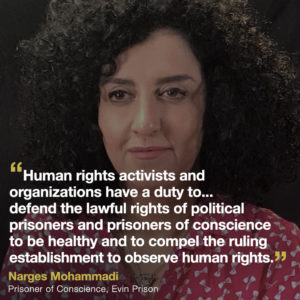

In a letter from Evin Prison on August 4, human rights advocate Narges Mohammadi raised concerns over the “high number of prisoners being held in [Evin Prison’s] women’s ward… at a time when in recent days the coronavirus has again started to spread.”

In a letter from Evin Prison on August 4, human rights advocate Narges Mohammadi raised concerns over the “high number of prisoners being held in [Evin Prison’s] women’s ward… at a time when in recent days the coronavirus has again started to spread.”

“The first step regarding the corona disease is to separate the sick from the healthy and impose quarantine but in reality, that’s impossible because of the high number of prisoners held in a small space,” she wrote.

“Human rights activists and organizations have a duty not to be silent toward the violation of prisoners’ basic human rights and to defend the lawful rights of political prisoners and prisoners of conscience to be healthy and to compel the ruling establishment to observe human rights,” she added.

There are also serious concerns about the condition of political activist Mohammad Ali (Pirooz) Mansouri, who continues to be denied furlough despite having suffered a heart attack in Rajaee-Shahr Prison, known for its inhumane conditions, in September 2021.

Furlough, temporary leave typically granted to prisoners in Iran for a variety of familial, holiday, and medical reasons, is routinely denied to political prisoners as a form of additional punishment.

“Despite the advice of the treating doctors, the prison’s health director and Dr. Hossein Ardabili, a surgeon who forbade my father’s continuing imprisonment after his surgery last year, the judicial system and the Ministry of Intelligence are preventing him from being granted medical leave,” said Mansouri’s daughter, Iran Mansouri, in an open letter in late June 2022.

Meanwhile, political prisoner Fatemeh Mosanna, who has been denied medical care for a variety of serious medical issues, including colitis and migraine, showed symptoms of COVID-19 in Evin on August 2.

COVID-19 outbreaks have also been reported in Saheli Prison in Qom, central Iran, the women’s ward in Orumiyeh Central Prison in the west of the country, and Rasht’s Lankan Prison in the north.

Prisoners at these locations have been denied adequate COVID-19 social-distancing measures and medical services.

Unlawful Denial of Treatment

Iran’s State Prisons Organization and judiciary chief, which are responsible for the safety of all prisoners, are required by domestic and international to provide proper medical treatment to inmates.

Yet under Judiciary Chief Gholam-Hossein Ejei—who along with his predecessor, current President Ebrahim Raisi, is a major human rights violator— political prisoners, including elderly inmates, continue to be singled out for harsh treatment, which often includes denial of medical care.

The threat of withheld medical care is also used as an intimidation tool against prisoners who have challenged the authorities or filed complaints.

This violates the Iranian Constitution, Article 29 of which has declared medical care and treatment as “universal rights,” while Articles 101 through 120 of the State Prisons Organization Regulations detail prisoners’ rights in regards to health and medical care.

In particular, Article 116 of the regulations requires prison directors to recommend pardons for prisoners suffering from serious medical issues.

Article 502 of the Code of Criminal Procedure also states that a prisoner’s sentence can be suspended if incarceration could make their illness worse.

Article 295 of the Islamic Penal Code meanwhile states that authorities can be held criminally responsible for negligence: “If a person abandons a task or particular duty assigned by law… and as a result a crime gets committed, that crime will be attributed to him as an intentional or semi-intentional act or a total error, depending on each case.”

Yet prisoners continue to be denied treatment, while human rights lawyers who tried to sue the Iranian government for its grossly negligent handling of the pandemic were sentenced to prison for the action.

Read this article in Persian