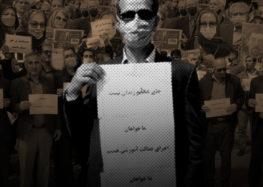

Imprisoned Labor Activist Dies of Stroke after Being Denied Medical Care

Authorities Routinely Refuse Medical Treatment to Political Prisoners

September 16, 2015—Labor activist Shahrokh Zamani died of a stroke on September 13, 2015, at Rajaee Shahr Prison in the Iranian city of Karaj, days after prison authorities refused him medical treatment.

Zamani had repeatedly gone to the prison infirmary during the previous days, reporting severe chest pains and requesting treatment at hospital, but his request was denied, a journalist in Tehran told the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran.

“For too long, the authorities have gotten away with blatantly denying medical care to political prisoners,” said Hadi Ghaemi, executive director of the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. “Prisoners perish and no one is held responsible; how many more must die?”

“Three, four days before Shahrokh [Zamani]’s death, he had chest pains and he felt pain in parts of his body. He went to the prison clinic several times but there weren’t any specialist doctors on those days and the general physician was not able to diagnose the problem. Mr. Zamani asked to be sent to the hospital several times but they did not transfer him,” Ahmadi Amouee stated.

Bahman Ahmadi Amouee, a prominent Iranian journalist who himself finished a five-year prison sentence in October 2014 for writing articles critical of the government, added that according to information he received from another prisoner at Rajaee Shahr, a specialist physician had arrived that morning to visit Zamani but his cellmates saw he was already dead.

“They noticed that his body had turned black and blood had come out of his nose. His left hand was in a fist. His cellmates took him to the prison infirmary and it became apparent he had suffered a stroke,” Ahmadi Amouee said.

Ahmadi Amouee recalled that during the time he shared a cell with Zamani at Rajaee Shahr Prison, “he was one of the healthiest prisoners. He ran every morning for an hour in the prison courtyard. He took showers every day and read books until late at night. He was a healthy person.”

“Zamani is only the latest victim,” said Ghaemi. “Unless there is an end to the systematic practice of denying medical care to political prisoners, more will fall.”

Prison authorities in Iran routinely refuse to provide critically needed medical attention to political prisoners, who receive harsher treatment than other inmates.

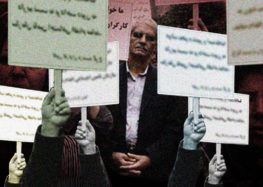

Bahman Ahmadi Amouee told the Campaign that Zamani’s death was the seventh death of a political prisoner at Evin and Rajaee Shahr Prisons since 2010. The others were Hamid Ghasemi, Hoda Saber, Mohsen Dogmechi, Alireza Karami Kheyrabadi, Afshin Osanloo, and Mansour Radpour. “They died because of various illnesses and lack of treatment and attention by the authorities,” he said.

Ahmadi Amouee added that there are a number of elderly political prisoners held at Rajaee Shahr Prison “who could fall into a dangerous situation at any time” if they did not receive immediate medical attention by medical specialists outside the prison. They include Atif Naimi, Amanollah Mostaghim, Foad Moghaddam and Jamalledin Khanjani. Saeed Razavi Faghih and Ramazan Ahmad Kamal, two additional prisoners denied medical care, are currently on hunger strike because their requests to be transferred to hospital were denied.

“These individuals were not given death sentences, but denying critically ill prisoners access to medical care is effectively marching them towards their deaths,” said Ghaemi.

Shahrokh Zamani, 51 at the time of his death, was a labor activist who worked as a house painter. He was sentenced to 11 years in prison in 2011 by the Revolutionary Court in Tabriz for “acting against national security by attempting to form house painters’ union” and “propaganda against the state.”

Labor unions are prevented from operating independently in Iran and labor leaders are systematically arrested, prosecuted under national security charges, and sentenced to long prison terms.

Like most other political prisoners, Zamani received harsh treatment in areas beyond the denial of medical care. He was never allowed prison leave, even though such furlough is typically provided to inmates in Iran, and was refused permission to attend his mother’s funeral and his daughter’s wedding. He was also not permitted in-person visits with family, which is the right of every inmate.

In 2014, Zamani wrote a letter to U.N. Special Rapporteur Ahmed Shaheed complaining about his mistreatment. “The Supreme Court clerk who reviewed my case said [there was] not a single legal argument that a judge could have relied on in my file to [support] a conviction. My wife was told there’s no point in trying to get justice for my case at the Islamic Human Rights office, and that the decision-makers are elsewhere,” he wrote.

In his March 2015 report, the U.N.’s Special Rapporteur for human rights in Iran noted with concern “reports of insufficient or nonexistent access to medical services for detainees,” adding that “Between April and December 2014, the [UN received] five communications concerning the deteriorating health conditions of 16 detainees in urgent need of specialized medical care outside prison. Some of these individuals were reportedly at risk of dying due to inadequate medical attention.”

The denial of medical care for prisoners directly violates Iranian law. Article 43 of the Iranian constitution requires “the provision of basic necessities for all citizens,” specifically referencing “medical treatment.”

The U.N. stipulates in its Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners that “Sick prisoners who require specialist treatment shall be transferred to specialized institutions or to civil hospitals.”