Sexual Molestation Case Involving 9-Year-Old Exposes Iran’s Weak Child Protection Laws

The family of a nine-year-old girl from a village in northwestern Iran has vowed to pursue legal action against the well-connected male teacher who sexually molested her.

Despite evidence confirmed by the Medical Examiner that the child had been sexually molested by her 30-year-old teacher, the court refused to issue a verdict of rape, opting instead for the lesser charge of “illegitimate relations.”

The court’s decision highlights the shortcomings of Iran’s child protection laws. Child molestation is not clearly defined as a crime in Iranian law, despite the Islamic Republic’s commitment to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Article 19 of the Convention on the Rights of the Child, which Iran became a party to in 1993 states, “States Parties shall take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse, neglect or negligent treatment, maltreatment or exploitation, including sexual abuse, while in the care of parent(s), legal guardian(s) or any other person who has the care of the child.”

Article 34 of the Convention calls on all states to “protect the child from all forms of sexual exploitation and sexual abuse.”

Iran’s Law for the Protection of Children and Juveniles, which came into effect in 2002, is vague on sexual abuse. Article 2 states: “Any form of abuse of children and juveniles that causes physical, psychological or moral harm and threatens their physical or mental health is prohibited.”

Article 5 describes child abuse as a general crime that does not need a private plaintiff for prosecution. But the law specifically excludes the term “child sexual abuse” and does not define punishment for it.

Nevertheless, Article 4 states: “Any form of physical or psychological harm, harassment, abuse or torture of a child constitutes deliberate neglect of the child’s health and well-being… punishable by three months and one day in prison with a maximum of six months in prison or a maximum fine of 10 million rials ($332 USD).”

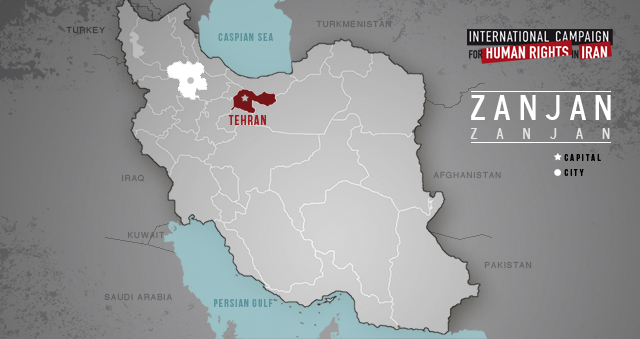

The facts of the current case are as follows. On May 1, 2016 a report about a girl referred to only as “Neda,” who had been sexually abused by her teacher at the 22 Bahman School in the village of Qareh Mohammad, was published by Alireza Jamatloo, the editor-in-chief of the Mardom-e-No newspaper of Zanjan city, located 178 miles west of Tehran.

According to the report, family members had come to the newspaper’s headquarters with a letter from the Medical Examiner’s Office and accused the 30-year-old teacher—a married man with two children—of sexually abusing their child.

“We were referred to the criminal court in Zanjan,” one of Neda’s relatives told the International Campaign for Human Rights in Iran. “We are not saying they didn’t investigate. They did. Even the medical examiner found evidence of bruises and other things that showed our child has been sexually molested, as stated in the official medical report.”

“But then the court said that the investigations had not found evidence of penetration and therefore it was not an act of rape, and hence issued a verdict for staying the proceeding against the teacher,” added the relative.

Neda’s relative continued: “The court acquitted the teacher of rape (zena-ye beh onf) and only agreed with the charge of illegitimate relations. This ruling can be challenged in the Appeals Court, but our question is: Can you apply the term ‘illegitimate relations’ when you’re dealing with a nine-year-old girl?”

Morteza Tamjidi, the education director of Zanjan Province, told the hardline Fars News Agency on May 2, 2016 that his department was investigating the case, but said that “the occurrence of rape is [an] inaccurate [charge].”

Internationally accepted definitions of rape extend beyond sexual intercourse to include forced or coercive sexual encounters.

Poor Family vs. Influential Teacher

Neda’s father is a seasonal worker with six children who is unable to financially support the family’s basic needs, her relative told the Campaign. She hated school and had to be chased with a stick to leave home every morning to get to class on time.

“The court did not listen to us. We live in a poor area. We are not in a good financial situation. But the teacher is rich,” the relative told the Campaign.

“One of his brothers is the head of the Ansar Khodabandeh Bank and another brother is a member of the Revolutionary Guards. They even sent a mediator and said they would pay us 60 million tomans ($20,000 USD) and give us a car [to drop the charges],” said the relative.

“They promised to support us for the rest of our lives if we agreed to put an end to the case. Well, if the teacher has not committed any crime, why did they offer us these things? We have a witness,” the relative told the Campaign.

Police Keep Case Details from Public

Zanjan’s Police Chief Gen. Alireza Salehi said on May 3, 2016 that the police had carried out their duty by arresting the accused teacher and delivering him to the judicial authorities. He was unwilling to further discuss the case.

“Information sharing should be done at an appropriate pace in order to avoid public anxiety,” he said.

But Neda’s relative told the Campaign that justice for their daughter was more important than concerns for “public anxiety.”

“[Neda’s] life and reputation have been destroyed,” said the relative. “Her rights have been trampled and her future is bleak.”

“But we will follow up on this matter,” added the relative. “The Zanjan Bar Association has agreed to take the case on for free. We will fight for our child’s rights. If they want to chop off our heads, they can go ahead.”

Iranians Discuss Taboo Topic on Social Media

Following the publication of Neda’s story, Iranians protested against sexual abuse by using the hashtag “#WhenIwas” on Twitter. Some users also shared their own bitter experiences online.

The tweets included discussions of how sexual abuse can result in lifelong physical and emotional scars, especially when the abuse occurs at a young age. In the absence of public education on the impact of sexual abuse, Iranians also talked about how societal and cultural norms perpetuate the fear of speaking out about sexual abuse while instilling a sense of guilt and moral anxiety in victims.