Iran’s Judiciary Commutes Death Sentences of Some Juvenile Offenders

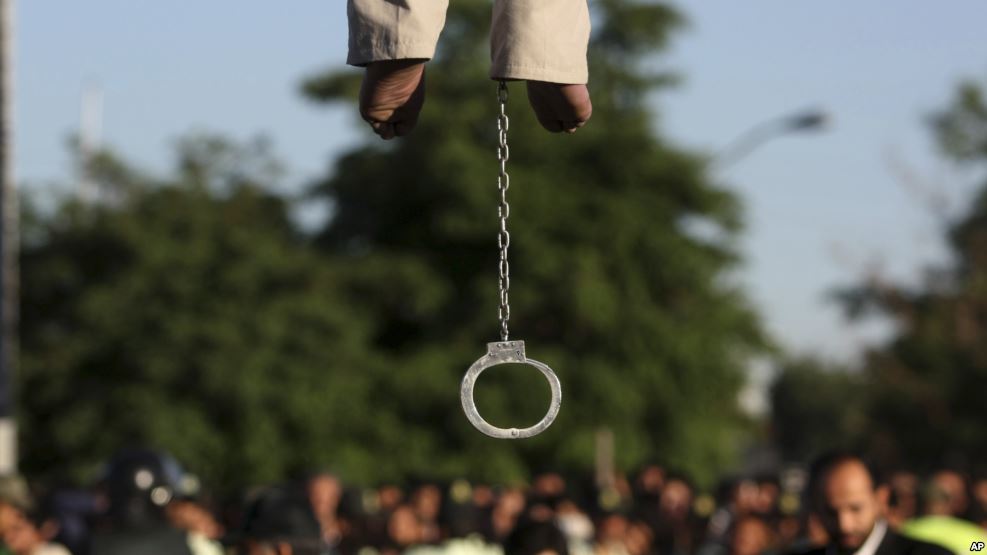

The Iranian judiciary has agreed to commute the death sentences of six people who were sentenced to death while they were juveniles while refusing the requests of four others, Tehran’s Prosecutor Abbas Jafari Dowlatabadi announced on February 8, 2017.

Rupert Colville, the UN high commissioner for human rights, welcomed the news on February 10 but said his “office nevertheless remains concerned regarding another juvenile, Hamid Ahmadi, who was 17 years old when he was sentenced to death for the fatal stabbing in 2008 of a young man during a fight.”

Colville added that the Iranian court relied on confessions allegedly obtained under torture while Ahmadi was at a police station and being denied access to a lawyer and his family “in violation of international guarantees of fair trial and due process.”

Ahmadi’s execution was set for February 11, but Colville cited reports that it has been delayed for 10 days.

Dowlatabadi said the decision to commute some of the death sentences was primarily based on Article 91 of Iran’s Islamic Penal Code, which allows death sentences to be reduced “if mature people under eighteen years of age do not realize the nature of the crime committed or its prohibition, or if there is uncertainty about their full mental development, according to their age…”

Dowlatabadi also said that the death sentences of 44 prisoners convicted of drug crimes were under review by a special committee set up by his office “to ensure no one’s life will be irreversibly taken by mistake.”

One of the six detainees who was saved from execution, Mohammad Ghaviandam, was convicted of committing murder when he was 13 years old. He was on death row for 17 years before his sentenced was commuted this month, according to a report published by the centrist Shahrvand newspaper on February 8, 2017.

No other information is available on the other five detainees who had their death sentences commuted, or on the four who remain on death row.

“Before the implementation of Article 91 in (the year) 2013, there were many cases of criminals under the age of 18 who were not mature enough to understand what they had done, but the law said they had to be hanged,” said Mohammad Kazemi, a member of the Parliamentary Committee on Legal and Judicial Affairs, on February 8, 2017.

“However, commuting the death sentence of six juveniles by the Tehran prosecutor is proof that Article 91 was a major reform that certainly conforms better with human rights standards,” he added

According to the International Covenant on Civil Political Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child, it is illegal to execute someone for crimes committed under the age of eighteen. Iran is party to both treaties, but remains one among a handful of countries still putting juveniles to death.

In his September 2016 report, former United Nations Special Rapporteur for Human Rights Ahmed Shaheed noted “with great concern that under articles 146 and 147 of the Islamic Penal Code, the Islamic Republic of Iran retains the death penalty for boys of at least 15 lunar years of age and girls of at least 9 lunar years.”

In an editorial published on Feb 9, the centrist Shahrvand news site described the decision to commute some of the death sentences as “a good development” and quoted Alireza Daghighi, the lawyer of one of the juvenile death row prisoners, saying that since 2013, the judiciary’s policy on punishing juvenile offenders had become “less theological and more logical.”