“Help Me Gain the Freedom I am Legally Entitled To,” Pleads Hunger-Striking Political Prisoner

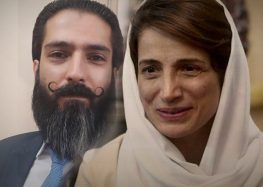

Mohammad Nazari has been imprisoned in Iran since 1994 for his membership in a separatist group.

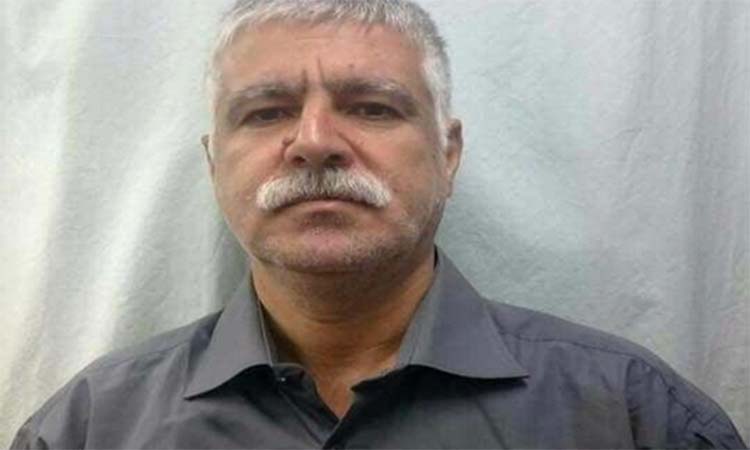

The life of one of Iran’s longest serving political prisoners, Mohammad Nazari, could “end in tragedy” due to a prolonged hunger strike, a source with knowledge about the case told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

“He has been refusing food since July 30, [2017], to demand a review of his case that could result in his freedom,” said the source, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “But he has no lawyer or family members to help him.”

The source added that Nazari was taken to the clinic in Rajaee Shahr Prison, located west of Tehran, “a couple of times and received IV shots, but he is being ignored by the officials and that could result in a terrible tragedy.”

“He is in a very bad condition,” said the source. “He has all sorts of physical problems and emotional issues. Losing his teeth is the least of his problems caused by the lack of medical attention.”

Political prisoners in Iran are singled out for harsh treatment, which often includes denial of medical care.

In an open letter from Rajaee Shahr Prison dated October 18, 2017, Nazari said he was eligible for release based on articles 10, 99, 120 and 728 of Iran’s Islamic Penal Code.

“If the law had been applied, I would have been freed four and a half years ago,” wrote the ailing political prisoner. “But invisible hands rooted in centers of power and the security establishment are preventing the implementation of the law in my case.”

“Now, in the 24th year of my imprisonment, I am alone, with no one to rely on,” he wrote. “I am on hunger strike because I have no options left.”

According to Article 10, “… if, after the offense is committed, a law is passed that provides mitigation or abolition of the punishment or security and correctional measures, or is favorable to the perpetrator in some other way, it is applicable to the offenses committed prior to the passage of the law until the final judgment is issued.”

“Don’t abandon me,” pleaded Nazari in his letter. “I don’t have anyone. My father, mother and brother were laid to rest years ago in the cemetery in Boukan. Your helping hand is my only hope. Help me. Help me so that my voice can be heard. Help me gain the freedom I am legally entitled to.”

A 45-year-old ethnic Azeri Turk, Nazari has been behind bars for more than 24 years, since his arrest on May 30, 1994, by Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence in the city of Boukan, West Azerbaijan Province.

In November 1994, Branch One of the Orumiyeh Revolutionary Court sentenced him to death for his alleged membership in the Democratic Party of Iranian Kurdistan (PDKI), an opposition group seeking autonomy for the mainly-Kurdish populated region of northwestern Iran.

The informed source who spoke to CHRI noted that after the penal code was amended in 2013, membership in the PDKI was no longer considered a crime.

“Mr. Nazari was charged with membership in the PDKI, but according to the new Islamic Penal Code, that is no longer a crime,” said the source. “He has written numerous letters to the authorities and asked for a judicial review, but so far nothing has been done.”

In 1999, Nazari received a pardon that reduced his sentence to life imprisonment. His many attempts to get a review of his current sentence have been ignored.

Nazari’s launch of his wet hunger strike coincided with the unannounced transfer of more than 50 political prisoners from Rajaee Shahr’s Ward 12 to the high-security Ward 10 on July 30, 2017.

At one point, as many as 20 of the prisoners were on hunger strike demanding the return of the personal belongings they were forced to leave behind during the move, and to protest the new wards poor living conditions.