Baha’i Leader Spent 10 Years in Prison, Authorities Incapable of Producing Any Evidence of Wrongdoing Throughout

Oppression Has Failed to Break Our Commitment to Our Faith, Says Leader

Oppression Has Failed to Break Our Commitment to Our Faith, Says Leader

The Islamic Republic of Iran has failed to suppress Baha’is by putting their leaders behind bars and denying them rights as equal citizens, according to a former leader of the persecuted community released after serving a 10-year sentence in prison.

“When I was preparing to get released, one of the prison staff asked me whether I had stopped believing in my faith after 10 years. Then he answered his own question and said, ‘No,’” Saeid Rezaie told the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) in an interview on February 20, 2018.

“He knew that the state had not gained anything from our incarceration,” said the Baha’i leader, “mainly because ofall the efforts by the civil rights activists, the media and people like you and your colleagues… [who] asked questions about the charges against us and shed light on the truth.”

Rezaie, 61, who was freed from Rajaee Shahr Prison in Karaj, west of Tehran, on February 16, 2018, is the fourth former Baha’i leader to be released in recent months.

Mahvash Sabet was freed on September 18, 2017, Fariba Kamalabadi on October 31 and Mahmoud Tavakkoli on December 4.

The four, along with other co-leaders Afif Naeimi, Jamaloddin Khanjani and Vahid Tizfahm, were arrested in 2008. They were all issued 20-year prison sentences in August 2010 for several charges, including “collaborating with enemy states,” “insulting the sacred” and “propaganda against the state.”

Their sentences were reduced to 10 years in prison each based on Article 134 of Iran’s Islamic Penal Code, which allows prisoners to serve only the longest sentence in cases involving convictions on multiple charges.

Rezaie told CHRI that imprisoned followers of the Baha’i faith only receive medical attention when their lives are in danger, and not for other ailments, including serious and painful illnesses.

“When there was an emergency, the authorities would allow treatment,” he said. “For instance I had asthma before I went to prison and during my time in prison I developed heart disease. When the authorities learned that the combination of the two was a life threatening condition, they allowed me to be hospitalized and I was operated on.

“But as far as illnesses that were very painful but did not put life in danger, they never allowed treatment. A year and a half ago I had multiple ligament tears in my knees, as diagnosed by the medical examiner, who recommended an operation and three months of physical therapy but the authorities did not allow it… This is how they treated us.”

Iran has a well-documented history of denying medical treatment for prisoners of conscience and political prisoners.

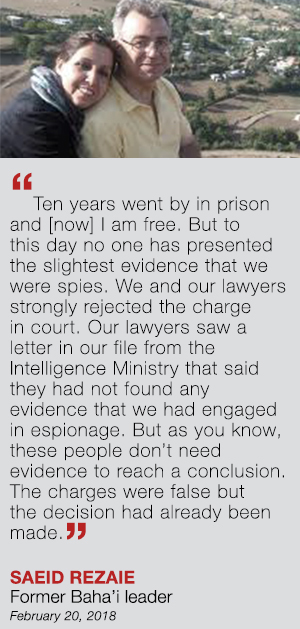

Rezaie said despite spending a decade behind bars, the authorities never presented any evidence to prove theiraccusations of espionage leveled against the seven Baha’is.

“Ten years went by in prison and [now] I am free. But to this day no one has presented the slightest evidence that we were spies. We and our lawyers strongly rejected the charge in court. Our lawyers saw a letter in our file from the Intelligence Ministry that said they had not found any evidence that we had engaged in espionage. But as you know, these people don’t need evidence to reach a conclusion. The charges were false but the decision had already been made.”

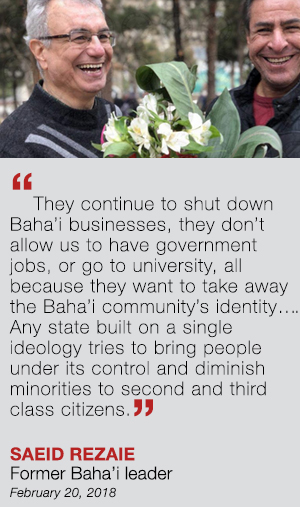

Rezaie said the Islamic Republic was bent on suppressing and marginalizing the Baha’i faith but the Baha’is themselves had no enmity towards the state.

“They want to take away our Baha’i faith and identity in any way they can. Any state built on a single ideology tries to bring people under its control and diminish minorities to second and third class citizens. This problem exists. It has hit us like a plague.”

“We were among the first citizens to come under pressure in the Islamic Republic and then many factions were also thrown out of the ruling circle. Yet we do not oppose anyone. We have differences but differences should not lead to confrontation.”

“For instance, we believe in equality between women and men. It is part of our teachings. But when we say it, they think we are posing a challenge and they start raising tensions.”

Rezaie continued: “They continue to shut down Baha’i businesses, they don’t allow us to have government jobs, or go to university, all because they want to take away the Baha’i community’s identity.

“Two of my daughters were arrested and imprisoned for a while. Then they took the national university entrance exam and got accepted. But they were expelled after one semester. These kinds of pressures have always existed. Of course, my daughters eventually studied online with the Baha’i Institute for Higher Education (BIHR), but even that’s not tolerated by the state. They want to shut it down but they can’t.”

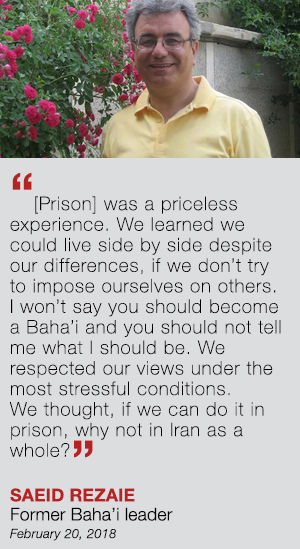

Asked about his experiences in prison, Rezaei said: “We were in Rajaee Shahr Prison in Ward 12, which was for political prisoners and prisoners of conscience. There were prisoners from all sorts of religions; Shias, Sunnis, Christians, Jews and Baha’is. We were all together. Even Turks, Kurds, Arabs and Baluchis, too.

“There were also prisoners from leftist factions, such as the Mojahedin Khalgh, members of Kurdish groups such asKomala and PJAK, as well as trade unionists, teachers and our reformist friends, too. It was a wide political spectrum but we all came to the conclusion that even though we were different, we should not confront each other.

“It was a priceless experience. We learned that we could live side by side despite our differences, if we don’t try to impose ourselves on others. I won’t say you should become a Baha’i and you should not tell me what I should be. We respected our views under the most stressful conditions. We thought, if we can do it in prison, why not in Iran as a whole?”

Rezaie ran a farm equipment company in Shiraz when he was arrested in May 2008.

“After I was arrested, I was put under a lot of pressure and my company closed within a year,” he told CHRI. “I was working with lots of different kinds of people in the farming business. I spent most of my time in the farms and the countryside. I loved nature. They took all of it from me… They took away my chance to be with members of society and to be of service.”

“When I went to prison, my son was 10-years old. He used to sit on my lap. I didn’t see him grow up into a teenager and now that I’m back home he’s a 21-year old young man. It’s a very strange situation. After 10 years, I don’t know how I’m going to restart my life again.”