Judiciary’s Intensifying Crackdown on Defense Attorneys in Iran Must End

Seven Human Rights Lawyers Detained or Blocked from Working in Iran in Less Than a Year

Seven Human Rights Lawyers Detained or Blocked from Working in Iran in Less Than a Year

August 14, 2018—An intensifying state crackdown on human rights defenders in Iran, in which the authorities have denied attorneys the ability to represent their clients and jailed them for attempting to do so, violates Iran’s domestic laws and international obligations and must end, the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI) said in a statement today.

Iranian authorities have charged at least three human rights lawyers and blocked at least four others from retaining clients over the last eight months.

“Iran is imprisoning lawyers for doing their job and depriving its citizens of one of the most basic human rights—the right to counsel of choice,” said CHRI’s executive director, Hadi Ghaemi.

“If the Iranian judiciary won’t abide by the law then it is the responsibility of the Rouhani administration and Iran’s parliament to address these violations of due process,” said Ghaemi, “and Iran’s Bar Association should take the lead in defending its own members.”

In addition to arresting defense attorneys, Iran’s judiciary has issued a list of 20 state-approved lawyers that detainees accused of “national security crimes”—the type of charge that’s usually issued against activists and dissidents—must choose from for legal representation.

The consequences of this assault on the legal profession in Iran are dire for attorneys and their clients: lawyers are sent to prison for defending their clients, and those whom they would represent are held for extended periods without charge, often forced to make false statements during interrogations, tried in brief trials where evidentiary standards do not meet international standards, and sent to prison by hardline judges handpicked to rule on “national security” cases for terms that can exceed 10 years.

7 Human Rights Lawyers Detained, Charged and Summoned

Nasrin Sotoudeh has been detained in Tehran’s Evin Prison since June 13, 2018, and is facing two national security charges for serving as the lawyer of a woman who was charged for removing her headscarf in public. Before her arrest, Sotoudeh had also strongly criticized the judiciary’s list of state-approved lawyers.

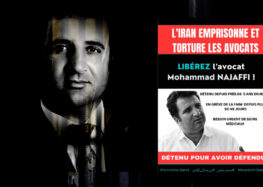

Mohammad Najafi has been in and out of detention since being arrested on January 15, 2018. He is facing eight national security charges for telling media outlets that local authorities concealed the true cause of Vahid Heydari’s death in police custody during Iran’s December 2017/January 2018 protests.

Iran’s judiciary has also blocked Najafi from retaining Payam Derafshan and Arash Keykhosravi as his lawyers; Najafi was told to pick a lawyer from a list of seven approved by the judiciary.

Mostafa Tork Hamadani was summoned to court and charged in July 2018 after criticizing the judiciary for barring him from defending environmentalists who were arrested by the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). Hamadani, who has taken on several human rights cases throughout his career, tweeted a copy of his summons document on July 26, adding:

“I was summoned to the Culture and Media Court based on a complaint by Tehran’s deputy prosecutor who accused me of spreading falsehoods. The reasons given in the complaint are my tweets about the late [Kavous] Seyed-Emami and the Note to Article 48 regarding the prohibition on lawyers against representing detained environmentalists…All my efforts are aimed at improving the climate for lawyers to defend the accused.”

Hossein Ahmadiniaz, the defense attorney in several cases involving basic rights in Iran, was summoned by Branch 4 of the Revolutionary Court in Sanandaj, the capital of Kurdistan Province on July 10, 2018, after he signed an open letter with 154 other lawyers criticizing Judiciary Chief Sadegh Larijani for restricting counsel for detainees held under national security-related charges.

According to defense attorney Payam Derafshan, he and his colleague Arash Keykhosravi were about to be arrested in February 2018 by the Intelligence Ministry’s office in Shazand, near Arak in Markazi Province, for giving legal counsel to fellow lawyer Mohammadi Najafi, “but the [Intelligence] Ministry in Tehran told us they had blocked it.”

In March 2018, defense attorney Mohammad Moghimi said he had been banned from retaining clients because he wasn’t on the judiciary’s “approved” list:

“The family of one of the people arrested in the recent protests contacted me and when I went to the judiciary to follow up on the case, I was told that I cannot represent this case because I have to be on a list,” he added. “I demanded to see this list but they didn’t have one. I said I have a license to practice law and that means I have the right to take this case. But they said based on Article 48, I’m not qualified.”

“What they want is someone who listens to them and won’t stand in their way. That’s a betrayal of the law. It will make lawyers more cautious and cause them to fear doing many things that could leave them off certain lists,” he added.

“The UN and the international community should forcefully register their condemnation of these blatant violations of law and of Iran’s international obligations,” said Ghaemi.

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Iran is a signatory to, recognizes in Article 14, subsection (3)(d), the right of an accused in criminal proceedings to be represented by legal counsel of his or her choice.

Iran’s Judiciary Uses “Note to Article 48” to Stamp Out Due Process

In January 2018, judicial offices in several Iranian cities received lists of lawyers that have been allowed by the judicial branch to take on cases involving national security charges at the preliminary investigation stage.

Iran’s Constitution sets no limits or conditions on the right to legal counsel.

Article 35 states, “Both parties to a lawsuit have the right in all courts of law to select an attorney….” According to Article 48 of Iran’s Criminal Procedures Regulations, people have the right to ask for and have a meeting with a lawyer as soon as they are detained.

However, the Note to Article 48 makes exceptions: “In cases of crimes against internal or external security…during the investigation phase, the parties to the dispute are to select their attorneys from a list approved by the head of the judiciary.”

This note also permits judicial authorities to delay an individual’s access to a lawyer by up to a week in cases involving alleged “crimes against the country’s domestic and foreign security.”

Yet CHRI has documented a consistent pattern over many years in which interrogations without counsel in these so-called national security cases actually goes on for many weeks. During this time individuals are routinely subjected to intense and unlawful threats and pressure to make false “confessions.”

The former UN Special Rapporteur for human rights in Iran noted in her March 2018 report her “regret” that despite the Bar Association’s call for a reconsideration of the restrictions on access to counsel in Iran, no changes had been made.

The judiciary’s official list has not been released to the public, but opposition sites have reported that the state-approved lawyers include those known for advocating harsh sentences, including the death penalty, for detainees held on political charges.

Many human rights lawyers have publicly criticized the list. In January 2018, 155 lawyers called on Iran’s Judiciary Chief Sadegh Larijani to stop restricting detainees’ access to legal counsel.

In March 2018, before the human rights lawyer Nasrin Sotoudeh was arrested and imprisoned, she said:

“We object to the judiciary chief’s indefensible behavior in introducing what amounts to discriminatory rules against the right to a fair defense, and if our objections do not result in reforms, we will take further action….If the head of the judiciary can stop lawyers from practicing, it’s time to say goodbye to this profession.”

In July 2018, the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute called on Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei to “take all possible measures to ensure that lawyers are allowed to carry out their legitimate professional activities without fear of intimidation, harassment or interference, in accordance with international human rights standards.”