Rouhani’s Telecom Minister Has Not Fulfilled Most of the Nine Pledges He Made Since Starting His Post

Since Mohammad Javad Azari Jahromi was approved by Iran’s Parliament as the minister of Information and Communications Technology on August 20, 2017, internet control, censorship and surveillance by the state have expanded significantly according to a review by the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

Before starting his new job, Jahromi suggested in his social media posts that he was a proponent of improving internet access in the Islamic Republic. But one year into his term, Iran’s youngest minister has done the bidding of the intelligence and security agencies by implementing policies that enable them to further censor and control the internet.

For example, the state has banned the widely used Telegram messaging app, blocking 40 million users in Iran from accessing their main mode of online communication, and for some, an integral business tool.

Despite Jahromi’s pledge to make it accessible, Twitter remains banned as well.

Jahromi’s ministry has also been working on blocking access to online censorship circumvention tools, such as virtual private networks (VPNs), which enable users to access banned or “filtered” websites and apps.

The internet and social media apps are heavily restricted and censored in Iran. Some 44 percent of the country’s 80-plus million people had access to the internet in 2016, according to the UN’s International Telecommunication Union. As a result, Iranian state policies and technical initiatives have increasingly focused on strengthening state control over the internet.

Despite presenting himself as a proponent of internet access, Jahromi has done nothing to counter cyber attacks conducted by state hackers that undermine online user security in Iran. He has also used his position as minister to pressure his critics in the press and state agencies to avoid criticizing him.

Jahromi’s previous career experience spoke for itself after President Hassan Rouhani appointed him to the ministry; his resume was made public during his confirmation hearings.

In August 2017, CHRI revealed Jahromi’s direct involvement with surveillance operations during the state crackdown on the peaceful protests in 2009 and allegations that he had personally interrogated activists.

CHRI has since learned that Jahromi had personally asked at least one political prisoner to hand over his email and social media passwords.

Two sources have also informed CHRI that Jahromi has used his position of power to prevent the publication of media articles that are critical of his actions. In one case, he intervened to block a state-funded news outlet from providing information to a media group that had criticized him in the past.

The sources requested anonymity for fear of reprisals by state authorities due to the pressure security and judicial officials impose on citizens to keep the details of their cases hidden from media outlets.

Launching Iran’s National Information Network

As the former chief of the Telecommunications Infrastructure Company (TIC) and the current minister of the Telecommunications Ministry (which the TIC operates under), Jahromi has played a major role in launching Iran’s state-controlled National Information Network (NIN).

The NIN has significantly enhanced the government’s ability to restrict, block and monitor internet use in Iran. For example, its search engines systematically filter keywords and phrases and send users to sites that deliver only state-approved and sometimes fabricated content.

NIN tools and services also facilitate the state’s ability to identify users and access their online communications, deeply compromising user privacy and security. The government steers Iranians toward use of the NIN and its search engines, security certificates, email services and video broadcasting services through price and internet speed incentives, violating net neutrality principles.

Critically, the NIN’s ability to separate domestic internet traffic in Iran from international internet traffic now allows, for the first time, the state to cut Iranians off from the global internet while maintaining access to domestic online sites and services.

As the NIN has progressed toward the final stages of implementation, the government’s development of a national network that provides faster and cheaper internet access has also led to the creation of a technical infrastructure that can more effectively block, censor, spread false information, and access Iranian users’ online communications.

Responding to a question from the hardline Tasnim News Agency on January 15, 2018, about NIN’s capabilities, the Ministry of Telecommunications confirmed that it could block access in Iran to the international internet as well as restrict access to domestically hosted online sites and apps.

Asked why all forms of internet access were blocked in Iran during nationwide protests in December 2017/January 2018, the ministry responded, “The restrictions are exclusively on international traffic but at the same time, NIN’s distribution capabilities totally allow for imposing restrictions on a regional basis.”

Not only has Jahromi overseen the acceleration of the state’s online censorship policies, his ministry has also proudly confirmed them.

Jahromi’s 9 Promises

In a proposal submitted by Jahromi to the Iranian Parliament on August 8, 2017, and in his interviews and social media posts during the past year, Jahromi has made nine pledges. On the occasion of his first anniversary as minister of telecommunications of Iran, CHRI has reviewed the statuses of these issues.

1) Fail: Reducing Internet Access Prices

Jahromi had promised that during his first 100 days as minister, he would ban internet service plan sales based on data usage. To carry out his pledge, Jahromi introduced a “fair usage” plan that ultimately proved unsuccessful.

Iranian internet service providers (ISPs) maintain low limits on data usage. Exceeding those limits requires users to make additional payments or they have to wait until the following month for their normal service to resume.

In essence, Jahromi’s plan called for reducing internet access costs. In practice, however, Iran maintains a two-tier system that makes it cheaper for users to access domestic websites, a violation of net neutrality principles.

According to the Rouhani administration’s “fair usage” rules, if a customer purchases a data plan with whatever amount of data, let’s say 160mb, the final price will be determined by the number of less expensive domestic sites that were accessed as well as the more expensive foreign content.

Under these rules, accessing content approved by the Telecommunication Ministry within the domestic network would cost 50 percent less than foreign content.

2) Unverifiable: Creating 100,000 Information Technology (IT) Jobs

During his parliamentary confirmation hearings in August 2017, Jahromi pledged to lay the grounds for the creation of 100,000 jobs in Iran’s IT sector.

“Of the 900,000 new jobs planned each year, 100,000 will be in IT, even though the president said he expected 300,000 jobs annually in this sector,” Jahromi said at the time.

In April 2018, Jahromi claimed more than 200,000 Iranians had found employment in internet IT during the past two years, but there are no official statistics to back up his claim. On the other hand, when the Telegram app was banned later that month, many Iranians lost their jobs, which relied heavily on Telegram’s social media network.

There are no official statistics indicating exactly how many people lost their jobs after Telegram was banned. But in January 2018, President Rouhani claimed 100,000 people had lost their jobs after Telegram was blocked for two weeks to quell the nationwide protests.

Due to the absence of official statistics, CHRI is not able to verify these figures. But if we accept Jahromi’s claim that in the past two years 200,000 jobs were created in internet IT, the loss of 100,000 jobs after Telegram was blocked means that the pledge to create 100,000 jobs per year has not been realized

3) Pass: Launching Domestic Messaging Apps

Although Jahromi did not publicly promise to contribute to the growth and development of messaging apps made and operated in Iran, in March 2018 Member of Parliament (MP) Abdollah Rezaian said Jahromi had stated that the government was working on the issue: “According to Mr. Jahromi, the problem facing domestic messengers is that they do not have sufficient capacity but he has emphasized that Iranian experts are devising plans to resolve the problem.”

Since the launch of the NIN during President Rouhani’s first term in office (2013-2017), Telecommunications Ministry officials and the Supreme Cyberspace Council (SCC), the highest state authority in internet policy-making, have used intimidation tactics and propaganda to encourage people to switch from foreign-made messaging apps, such as Telegram, to domestic varieties.

Foreign-owned and with its servers based outside Iran, Telegram is not under the control of the country’s state censors. The authorities’ willingness to disrupt what has become the principal means of digital communication in Iran—and since the ban, to disrupt access to circumvention tools—demonstrates the primacy of their commitment to state censorship.

The pressures culminated into the state’s blocking of Telegram on April 30, 2018. Meanwhile, state agencies were banned from conducting any activities on the network and Iranian developers were granted financing under extremely agreeable terms without any preconditions.

According to the SCC’s secretary, Abolhassan Firouzabadi, the loans were also offered at zero percent interest. These policies resulted in the launch of five Iranian messaging apps.

In addition, a few months after the authorities blocked millions of Iranians from accessing Telegram, millions of citizens started using domestic-made versions of the original Telegram app, which allow the state to censor content and violate user privacy.

Telegram Talaeii (Telegram Gold) and Hotgram, the only Telegram-based apps now available on the Iranian app store, Cafe Bazaar, both censor content according to state policies.

Cafe Bazaar was ordered by the Iranian government to remove all versions of Telegram from its app store, except the state-approved Telegram Talaeii and Hotgram.

An examination of these two apps’ sudden growth following the state’s ban on Telegram suggests that the influx of domestic apps in the Iranian market was part of an orchestrated plan by senior officials to replace Telegram with native versions that the state can control and monitor.

After Telegram was banned, Rouhani declared that the government had no hand in suppressing the network and blamed the ban on the judiciary. But it has since become evident that the government instructed the TIC to allow users to access state-approved Telegram content exclusively through Telegram Talaeii and Hotgram.

Exactly who owns the company that offers the two apps that were created based on Telegram’s open source code, Rahkar Sarzamin Houshmand (Smart Land Solutions, SLS), is unclear.

However, the backing and words of support the company has been receiving from some senior Iranian officials, and the disappearance of all other versions of Telegram in the Iranian app store, shows that the government is determined to make Telegram Talaeii and Hotgram the primary gateways to Telegram data in Iran.

If Iranians try to download any other domestic versions of Telegram, the following message is shown on the screen: “This app has been unpublished by the order of the Workgroup of Determining Instances of Criminal Content.”

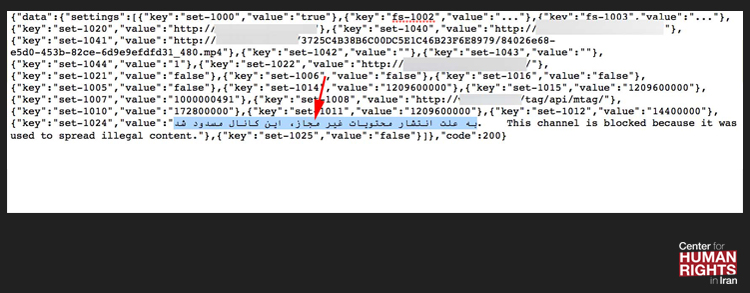

Users in Iran are also blocked from accessing channels that have been censored by the state on Telegram Talaeii and Hotgram.

Screenshot of the code on Telegram Talaeii and Hotgram that inform users a channel has been blocked.

Blocking Telegram on the one hand, and then allowing users in Iran to access it exclusively through state-approved Iranian versions of the app, has enabled state agencies to monitor and censor all of the app’s traffic.

The Rouhani administration has avoided acknowledging its own role in facilitating this clear violation of online user privacy in Iran. But some officials have tried to bring the inherent privacy problems of Telegram Talaeii and Hotgram into public view.

On June 30, 2018, Rasoul Saraian, the head of the Information Technology Organization (ITC), an agency operating under the Telecommunications Ministry, announced that the two domestic apps must address their security issues.

“The managers in charge of these apps have one week to give a transparent response regarding the kinds of information they collect from their customers,” he told the state-run Islamic Republic News Agency (IRNA).

To date, SLS has not responded and both the Telecommunications Ministry and the ITC have not issued the report they had pledged to commission to inform the apps’ collective 30 million users of potential privacy issues.

4) Unverifiable: Adding Women to Iran’s Telecommunications Ministry

Jahormi had pledged that by the end of Rouhani’s second term in 2021, 30 percent of his ministry’s managerial posts would be occupied by women.

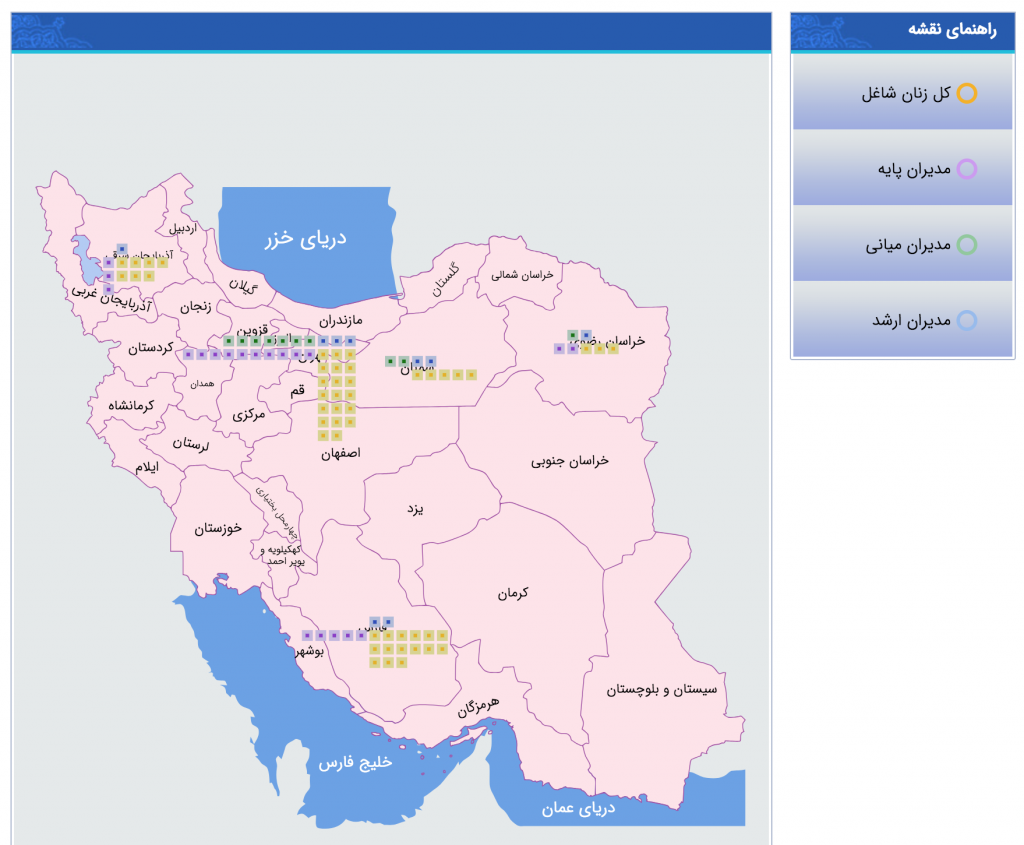

According to the Telecommunications Ministry’s website, 5,830 women are currently employed by the ministry in various positions. But Jahromi has appointed only nine women to senior managerial positions.

A map on the ministry’s website also indicates that out of 31 provinces, women are only employed at five branches of the ministry in Tehran, Semnan, East Azerbaijan, Khorasan Razavi and Fars provinces.

A map on the ministry’s website shows women are not employed at most of the ministry branches.

5) Fail: Unblocking Twitter

Jahromi had pledged that he would make Twitter accessible again in Iran when he became minister but it remains banned one year later.

In May 2018, Jahromi was among six of President Rouhani’s cabinet ministers who signed a joint letter calling for Twitter and YouTube to be unblocked.

But according to MP Ramazanali Sobhanifar, who’s also a member of the state’s Working Group for Determining Instances of Criminal Content (WGDICC), state officials aren’t even considering the issue.

Sobhanifar, who also signed the joint letter, told the Fars News Agency on June 30, “The matter was put aside after the prosecutor general’s negative response to the letter and it won’t be pursued further.”

“The filter on Twitter was imposed through a court order and later by the WGDICC,” he added. “The prosecutor’s office is of the opinion that the issue cannot be raised again because the court has made a ruling on it.”

6) Fail: Relaxing Iran’s Online Content Censorship Policy

Since starting his post as telecommunications minister, Jahromi has called for relaxing the state’s censorship of online content and apps in Iran, particularly Twitter.

“We cannot deny people from using cyber services but we are making an effort to block immoral content,” said Jahromi in an interview on state TV on August 26, 2017.

And at a roundtable discussion on March 17, 2018, he said, “The road to paradise does not go through a filter.”

Some sites have been unblocked during Jahromi’s term, including Zoho, Goodreads, and Google Drive. But there has been no fundamental change in Iran’s policy of censoring and filtering websites and apps deemed “immoral” or “inappropriate” by state agencies.

Some sites and apps are unblocked while others are blocked; the cycle continues.

Jahromi has meanwhile spearheaded efforts to make sure blocked sites and apps are not accessed in Iran by any means.

After Telegram was banned, Jahromi announced that the Telecommunications Ministry was working on a project to block circumvention tools in Iran. As a result, for several days following his comments, internet access was severely disrupted and nearly impossible in Iran.

Indeed, during Iran’s December 2017/January 2018 nationwide protests, the Telecommunications Infrastructure Company (TIC), which operates under the Telecommunications Ministry, blocked circumvention tools and caused severe internet access disruptions that had international ramifications.

On May 15, 2018, Jahromi defended the action without showing concern for user security, telling reporters, “In light of widespread use of circumvention tools, the TIC took action on orders of the president within the SCC guidelines, and there’s logic behind it.”

CHRI’s investigations have revealed that the TIC temporarily rerouted Telegram’s traffic inside and outside Iran by illegally changing the app’s internet protocol (IP) addresses.

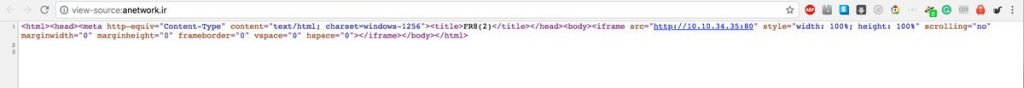

The TIC used the same “code injection” method on other sites, including Fileniko, which made the site unavailable to people outside Iran as well. Fileniko has since been unfiltered in Iran and the Telecommunications Ministry has not explained why it was banned in the first place.

Screenshot of the code injected into fileniko.com so that the website redirected users to a different website, http://peyvandha.ir/, which displays a list of websites recommended by Iranian authorities.

Filtering websites in this way could be an indication that there are major projects underway to make apps and websites that have been banned by the state completely inaccessible by any means, including circumvention tools. However, this method is only effective on sites hosted inside Iran.

This method of censoring online tools and content, implemented by the Telecommunications Ministry, had never before been used in the history of Iran’s internet. Jahromi has been silent on about its destructive impact and violations of user privacy.

7) Fail: Creating Startup Giants in Iran

Jahromi had promised to generate 100,000 online jobs annually with the creation of “giant technology startups,” but the state’s banning of Telegram forced many of those who relied on the app for generating revenue into bankruptcy while creating operational problems for others who saw their websites blocked in Iran without “any legal justification.”

For example, PayPing, Iran’s version of PayPal, has been blocked by the state on several occasions—despite the company’s efforts to comply with state laws—most recently in May 2018. Its CEO, Saeed Mashhadil, wrote in an open letter:

“The story of the creation and operation of fintech startups in Iran is so obscure and disheartening that there is no need to get into the long details about how entrepreneurs do not get any support in this country. Since our launch, we have tried to work within the law. We have made efforts beyond the wishes of law enforcement agencies to create a secure and suitable environment where no illegal transactions could take place. We have reported criminal behavior to the authorities and monitored and blocked the accounts of suspicious individuals.”

He added: “At the same time, we have welcomed all joint meetings with the Central Bank and the Electronic Card Payment Network and insisted that they should formulate a transparent law. At every meeting, we were promised that laws were being written to organize the operations of fintech companies. But these promises have not come true and PayPing was filtered for a third time on May 23, 2018, without any legal justification.”

The state’s arbitrary censorship policy thus remains one the biggest obstacles to the growth of technology startups in Iran.

8) Fail: Investigating the Hackers Who Targeted an Iranian Charity

When the Imam Ali’s Popular Students Relief Society (IAPSRS), a charity based in Iran, tweeted in April 2018 that its staff had been hacked, Jahromi responded: “This evening I asked a committee headed by the ministry’s security director to pursue and investigate this matter and publish its findings. I also recommend that a complaint be filed with judicial authorities.”

But Jahromi failed to follow up on the case and according to the organization’s chairman, he hit a wall after filing a complaint.

In a tweet on June 22, 2018, the society’s chairman Mohammad Taleghani tweeted: “We went to court and lodged a complaint and then the case was referred to the FATA cyber police, where an official told me that the hack originated in Iran. The result of the investigation shows that the matter cannot be pursued because the hackers used VPNs [which concealed their identities].”

Taleghani continued, “The assistant prosecutor told us to give him a new reason to investigate the matter. We said we already have a hacking case; what do you mean? He replied, I don’t know! You tell me!”

In reply to Taleghani’s tweet, Jahromi wrote: “Investigations so far have not proven that there were ‘unauthorized’ attempts to access activation text messages through mobile operators. Some of these cases are related to international hubs that act as intermediaries in exchanging text messages and we are looking into them. As for ‘authorized’ access, we have pursued the matter with the Supreme National Security Council (SNSC).”

However, CHRI’s investigations show that the IAPSRS staff accounts were compromised when text messages containing their verification codes were hijacked. Therefore, individuals must have carried out the hacks with access to Iran’s telecom infrastructure.

This method has been frequently deployed to break into the accounts of members of Iranian civil society, particularly journalists. Based on CHRI’s investigations, from July 23-August 5, 2018, at least 10 Telegram and email accounts belonging to journalists working for reformist newspapers in Iran were targets of this type of cyber attack.

People on Twitter have reminded Jahromi of his promise to publish the ministry’s report on this specific case, but he has failed to do so more than five months later.

9) Fail: Investigating User Account Fraud on Domestic Apps

In response to complaints that users in Iran were being registered on the domestic Soroush messaging service without their permission, Jahromi said on May 30, 2018, “The National Cyberspace Center is investigating uncertainties regarding non-voluntary memberships created on the Soroush messenger.”

Soroush has denied the existence of the fake accounts but many users have posted screenshots of the unauthorized use of their names and profiles on the app.

To date, Jahromi has not only failed to investigate the claims. On June 2, the National Cyberspace Center announced it had not even received “any evidence” from the Telecommunications Ministry to launch an investigation.