Iranian Lawyer and Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Shirin Ebadi: “The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran Is the Most Important Obstacle to Women’s Rights”

On the occasion of International Women’s Day, March 8, Iranian lawyer and Nobel Peace Prize laureate Shirin Ebadi shared her thoughts on the state of women’s rights in Iran in an interview with the Center for Human Rights in Iran (CHRI).

Mrs. Ebadi has long been a defender of women’s rights in Iran, working to address the widespread discrimination women face in personal status and family law, employment, education, travel, political office, citizenship and other areas.

Born in the city of Hamadan in northwestern Iran, Shirin Ebadi received her law degree in 1969 and her doctorate in 1971, both from the University of Tehran. She was the first female judge in Iran’s history. Mrs. Ebadi founded the the Defenders of Human Rights Center (DHRC) and received the Nobel Peace Prize for her human rights work, the first Iranian to do so, in 2003. She has been extremely prominent in the defense of women’s and children’s rights in Iran and has also defended many dissidents during her career. Mrs. Ebadi has resided outside Iran since 2009, due to persecution by state authorities for her human rights work.

In this interview, the prominent lawyer spoke of the challenges women face in Iran, and the critical role of both individual acts of bravery and the international community’s commitment to support human rights. Mrs. Ebadi forcefully stated her view that Iran’s Constitution—and a political structure that hands ultimate political authority to an unelected Supreme Leader—are the principal obstacles to women’s rights in Iran. She also registered her disappointment with President Hassan Rouhani, whom she noted pledged much but did not fulfill his promises on women’s rights. The full interview follows below.

“As long as the Constitution remains as is, women in Iran will never gain equal rights.”

Shireen Ebadi, lawyer, Nobel laureate

Legislation currently pending in Iran, “Ensuring Women’s Security Against Violence,” has been sent for clerical review in the city of Qom. What are your thoughts on this legislation and its future?

Although the draft of this law has numerous shortcomings, passing the law will be better than the lawlessness in Iran. Unfortunately, the Executive Branch has also been passive in this regard. Most importantly, setting a rule is not enough. Other actions are necessary too. I’ll give an example: Nowadays, according to the law, if a woman proves that her husband is violent and abusive, she has a right to divorce. But if she isn’t financially independent and the government has not designated support organizations for divorced women, how can she use her legal right to divorce? Say she goes to court and is believed and given permission to divorce. But after separation she needs to leave the husband’s house. Now what’s a woman in her thirties to do without a job or income? There are no support organizations in Iran to anticipate the needs of women in such conditions. So despite the necessity of this law, its mere existence is not enough.

Are there steps women’s rights activists can take to contribute to the elimination of discrimination against women in Iran?

Women’s rights activists must use every possible outlet to stimulate society and public thought and there are many different methods. Because the innovation of women in this field is very effective.

I remember when the Law of Custody was changed after the death of Aryan Golshani [the young girl who was given to her father at age 7 after her parents’ divorce, as per Iranian law, and died at age 9 after being starved and beaten by her drug-addicted father]. Aryan had been left in her father’s house after the parents’ divorce because of a flawed law, and her death led to positive changes in custody laws with regards to women. In fact, the horrendous death of a little girl revealed the flaws of the law and moved society to demand a change in custody laws. So the innovation of women’s rights activists is very important when it comes to what needs to be done at different moments.

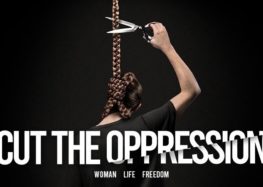

Another example is Vida Movahhed [the young woman who protested forced hijab by removing her headscarf in public, initiating a broad civil disobedience movement in which scores of men and women publicly protested compulsory hijab] who did something very innovative and important and drew a lot of attention to her work. She stood on a platform and took off her scarf and hung it on a stick. Her creativity moved society and made people reevaluate compulsory hijab. Reaching the destination alone is not enough. We need something to move with and it’s the role of women’s rights activists and their innovations to decide how they want to cross this path.

Regarding women who face intersectional discrimination, including women from the LGBTQ community, women with disabilities and women from ethnic and religious minorities, do you think their experience and needs are properly considered in the Iranian women’s rights movement? What are some measures you would recommend to foster inclusiveness in the movement?

I must admit honestly that there isn’t a lot of attention paid to these issues as it should be. It’s critical to pay extra attention to such problems. At the same time, I should add that people in these groups who face intersectional discrimination must raise their voices so that both society in general and women’s rights activists start to notice and hear them and their needs.

What are the main obstacles for women to change their situation? How does the state crackdown on civil society, the imprisonment of activists and restrictions on the operation of independent media and civil society organizations affect the women’s movement?

The state crackdown on activists and restrictions on the operation of independent media and other things you named are all obstacles to women’s rights movements. But I must add that the most important [obstacle] is the Constitution. Because the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran is founded on discrimination and its structure enforces institutionalized discrimination on the Iranian people. So as long as the Constitution remains as is, we will never gain equal rights in Iran. The Constitution states that all laws must be in accordance with Islamic sharia and approved by the Guardian Council’s six faqih members who are directly chosen by the Supreme Leader. In the Constitution, we read that all laws must be in accordance with Islamic sharia, but in fact what it truly means is that all laws must be approved by the Supreme Leader who has life tenure and is chosen not by the people but by a group of clerics, and the Supreme Leader is the ultimate political authority. In a system like this, inequality and discrimination isn’t so surprising. That’s why we see, on the occasional instances when a proposed law can benefit women, that it isn’t passed by the Guardian Council because it’s not in accordance with Islamic law. So the current structure of the Constitution will never allow room for equality and the elimination of discrimination.

How do you evaluate the Rouhani administration’s performance and policies towards women’s rights?

I find his policies all empty verbal promises. Rouhani gave a lot of promises supporting women’s rights and equality so that he could gain women’s votes during the presidential elections. But none of his promises were fulfilled—even when it came to issues that essentially have nothing to do with the sharia and the Constitution did not prohibit them, such as women’s presence in stadiums. But Rouhani could not fulfill his promises. Even in Isfahan, when they projected a soccer match in a public park, the organizer of the event was arrested on charges of “threatening public chastity.” Rouhani just stood there like a statute and watched all this happen. Generally, I don’t find Rouhani’s human rights record very positive, especially when it comes to women’s rights.

Forty years after the Islamic Revolution, how do you assess developments within the legal system regarding women? What are the major achievements and set-backs?

Instead of considering the forty-year history, I recommend going back forty-one years. I mean we should compare the situation now with what it was like before the revolution. Where were women in 1978 and where are they now? Forty years alone is not enough for an evaluation. We should evaluate the past forty-one years and we’ll see women’s condition is far behind what it was forty-one years ago.

How can the international community help support the rightful demands of Iranian women?

There are various methods that can help women achieve their human rights goals. For example, when women’s entrance to stadiums is prohibited, international federations such as FIFA should sanction Iran and not allow the national team to play [until women are allowed]. Or when women are prohibited from singing publicly, UNESCO must take action. There are a lot of methods like these that the international community can adopt.